Scientists drill for oldest ice to reveal secrets about Earth’s climate

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.5214

Over about seven weeks in December and January during the most recent austral summer in Antarctica, a team of researchers from Europe drilled the first 808 meters of an intended 2700-meter ice core; 10 Australian scientists traversed 2300 kilometers round trip across the continent from a year-round research station to where they plan to start deep drilling next season; Japanese researchers selected a drilling site; a Russian team worked on an upgrade to its station; and US researchers drilled a couple hundred meters into the ice sheet of Allan Hills.

Those teams—and ones from South Korea and China—are all after the same thing: the oldest ice.

In the late 1990s, several teams drilled to around 3000 meters in the interior of Antarctica. The cores dated to varying ages, with the one obtained by the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) going back farthest, to 808 000 years.

Around 20 years ago, scientists from around the world together set the goal of retrieving two or more continuous ice cores that go back 1.5 million years. Marine sediments show that ice-age cycles subsequently stretched out from about 40 000 years to roughly 100 000 years and became more extreme, in what’s known as the Mid-Pleistocene Transition. “We want to get ice cores that go back to the 40 000–year cycles,” says Eric Wolff, a University of Cambridge professor of Earth sciences who coordinates international partnerships for drilling old ice. “The idea is to see what happened to carbon dioxide and to figure out why the cycles changed.”

Air trapped in old ice contains a unique archive of the ancient atmosphere. Ice also preserves dust and the isotopic makeup of water. Ice cores can shed light on many aspects of Earth’s climate, including greenhouse gas concentrations, ocean and surface temperatures, and sea level. They are the only way to directly measure ancient CO2 levels, notes Edward Brook, a paleoclimatologist at Oregon State University and director of the NSF Center for Oldest Ice Exploration (COLDEX). The big question is, he says, “How sensitive is the Earth system to high levels of carbon dioxide?”

The teams from around the world are in a collaborative competition, says Wolff. “We actively help each other with ideas, how to date ice, and sometimes with flights and other logistics. But we’d all like to be the ones to get the first data.”

Selecting drill sites

“It’s not like you get a better drill and drill deeper,” says Brook. “The challenge is to figure out where the oldest ice is preserved.” Ice is always flowing, and in most places the oldest ice is gone, he says. “But the international ice community believes there should be places where you can get continuous records to 1.5-million-year-old ice.”

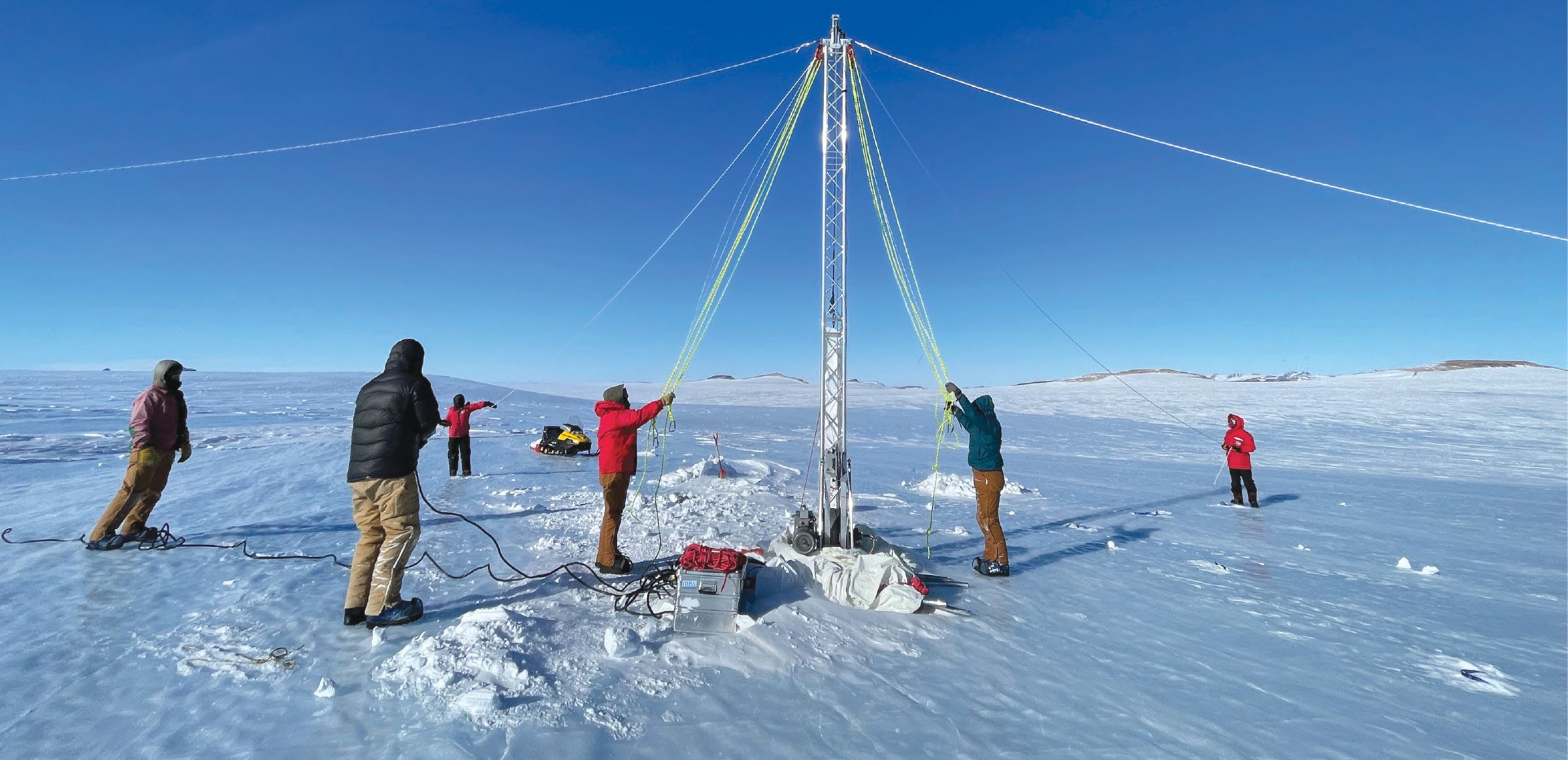

A drilling tower at Allan Hills, Antarctica, in December 2022. Chunks of multimillion-year-old ice discovered there have made finding more a priority of the US team.

PETER NEFF

In searching for promising sites, the teams use ice-penetrating radar data and ice-sheet modeling. “You are looking for the right thickness and topography,” says Robert Mulvaney, a glaciologist with the British Antarctic Survey. The ice needs to be deep to get the best time resolution. But if it’s too deep, then geothermal heat can melt the ice, he explains. EPICA drilled to 3200 meters, he says, “and any ice older than 800 000 years had melted.” Likewise, the Russian team’s Vostok core, which was drilled over several decades, was folded and deformed at the bottom. In 1998 the core exceeded 3600 meters in depth and recorded 420 000-year-old ice.

Based on ice-flow data, the Russian team is targeting its search about 300 kilometers upstream of its original borehole. The team’s plans are not yet funded, says Vladimir Lipenkov, head of the Climate and Environmental Research Laboratory at the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute in Saint Petersburg, but “the chance of securing funding from the government will improve with completion of the new Vostok station.” The Russian team hopes to begin drilling in the 2026–27 austral summer.

In 2015–16 Beyond EPICA—as the new phase of the European project is known—used airborne radar to narrow its search for a potential site. Mulvaney spent the next two austral summers towing a surface radar across the 16 km × 12 km area at 9 km/hr to get a better sense of the ice layering. “We were lucky to find a site only 40 kilometers from our existing Concordia Station,” he says. Beyond EPICA has €11 million (about $11 million) for 2019–26 from the European Commission, plus money or in-kind contributions from each of the 10 participating nations.

The countries that have already selected drilling sites have each found them reasonably close to their respective Antarctic stations, which is useful from a logistical standpoint. Australia, which is joining the game this go-around, has a site a few kilometers from the Beyond EPICA drilling site.

Old—and older—ice

Last summer Sarah Shackleton, part of the COLDEX team, dated a section of discontinuous ice from Allan Hills to 4 million years. The Princeton University postdoc’s finding built on the nearby discovery of 2.7-million-year-old ice, which shifted the COLDEX plans. A continuous core is still a goal, says Shackleton, but now the team is taking a multifaceted approach in its search for old ice.

COLDEX’s first aim is to look for more multimillion-year-old ice in Allan Hills, which is about 110 kilometers northwest of McMurdo Station, the US logistics hub. The shallow area, on the edge of a mountainous subglacial ridge, traps ice that has been dragged up toward the surface by glacial flow.

The second step for COLDEX—to begin next year pending availability of logistics resources from NSF—is to drill a core around 1100 meters deep in Allan Hills. Jeffrey Severinghaus is a geosciences professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. He hopes that the team finds old ice with better resolution: Instead of 4-million-year-old ice “being squished” into a 1-meter-thick layer of ice, “maybe it will be spread over 60 meters,” he says. “That would let us learn more about changes in climate.”

As its third component, the COLDEX team plans to drill a continuous 1.5-million-year-old core. That would need to be somewhere other than Allan Hills. COLDEX is funded at $25 million for five years through 2026. The site will be chosen by then, says Brook, and, if COLDEX is renewed for five years, drilling would begin later in the decade.

In seeking a site for drilling a continuous core, the US will deploy a new rapid-access tool, the ice diver, that can date the ice near bedrock. A flanged barrel with roughly the diameter of a soda can, the ice diver melts vertically downward, steered by a pendulum system and powered by a high-voltage, surface-based electrical generator. Control signals and data are transmitted via an attached cable that unspools from the device as it descends. For COLDEX, the ice diver will observe scattered blue laser light to profile dust concentration as a function of depth. “By comparing to other records we can translate dust cycles to ice ages,” says Dale Winebrenner, a research professor in Earth and space sciences at the University of Washington and one of the developers of the ice diver.

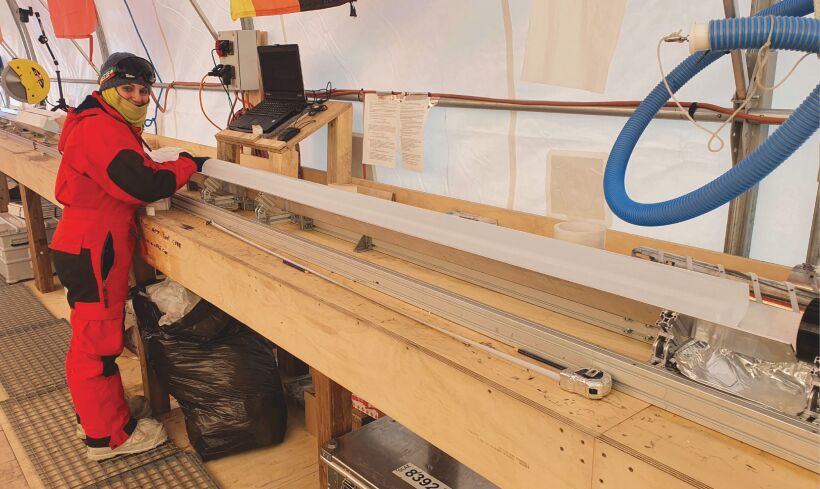

Giuditta Celli, a PhD student at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, logs a freshly drilled ice core for the Beyond EPICA project.

PNRA/IPEV

“Even with high-quality, advanced radar,” says Severinghaus, “it’s still hard to say how old the ice is down near the bottom.” And, he says, it takes five years and $50 million to drill a deep ice core. Determining the age of ice with the ice diver before drilling will increase the chances of obtaining old ice. Winebrenner and colleagues plan to conduct tests with the ice diver this summer in Greenland and to deploy it in Antarctica in the 2024–25 austral summer. For now, each handmade, single-use device costs around $20 000. The instruments and cables are left in the ice after use.

Drill, log, store, probe

Ice cores are extracted with cylindrical drills, typically about 3 meters in length and with core diameters of about 10 cm. The drill descends attached to a cable, which powers the drill rotation. When the drill barrel is full, the drillers break the core from the ice below. They raise it, remove the ice core, clean the drill, and then lower it back down the hole.

“Ideally, you deliver 3 meters of ice each time,” says Mulvaney. “But it doesn’t work that way. You run into problems.” At depths of roughly 500–1000 meters, the pressure in the bubbles makes the ice brittle and easy to shatter; deeper, clathrates form and the brittleness dissipates. Each round of drilling takes more than an hour—longer as the hole deepens. The Beyond EPICA team introduced a 4.5-meter barrel this year, Mulvaney says. “We hope to reduce the number of trips down.”

“It’s always nerve-racking if you are the one operating the drill,” Mulvaney says. “You have to get a decent core and bring it back up without losing the drill. And you worry about getting the drill stuck and breaking the cable.” He recalls when a drill got stuck during EPICA. “We had to start over with a new borehole. We lost a couple of years.”

Scientists label and log the ice core in segments. They note any damage, and they write the depth and orientation directly on the ice. The next core will be matched to it.

The Beyond EPICA team is testing transportation of ice cores at –50 °C. “Maintaining the low temperature poses problems when crossing the hot equator,” says project spokesperson Carlo Barbante, director of the Institute of Polar Sciences and a professor of analytical chemistry at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. Until now, ice cores have generally been transported and stored at standard freezer temperatures of –20 °C. But, explains Barbante, the lower temperature decreases diffusion of the trapped gases.

The COLDEX team, at least for now, will stick with –20 °C for transporting and storing ice. “It’s a trade-off between the cost and how much the science is affected,” says John Higgins, a Princeton geoscientist and lead for COLDEX’s shallow coring. “We feel that –20 °C, –30 °C is okay.”

Ice cores are transported back to researcher teams’ home countries for study. The main US storage facility is in Denver, Colorado.

PETER NEFF

In the past, some of the ice analysis was done near the site of extraction. Nowadays the instruments are more sophisticated and harder to transport and maintain in the cold. So researchers retrieve ice-core segments from their home storage sites—the main US one is in Denver, Colorado—and study them in their labs.

Fossil air

One of the main methods to date very old ice is to measure the ratio of argon-40 to argon-38 found in air bubbles. The lower the concentration of 40Ar, a decay product of potassium-40 from the Earth’s crust and mantle, the older the ice. Other dating methods include counting annual ice layers, matching them to known volcanic events or variations in Earth’s orbit, modeling glacier flow, and using methods based on air–hydrate crystal growth or radiometric dating with krypton-81. Ice age can also be logged on coarser time scales by the amount of trapped dust and by Earth’s magnetic reversals: When the field is weak, more cosmic rays enter the atmosphere and, through collisions of oxygen and nitrogen, introduce transient maxima in beryllium-10, which is archived in ice.

With confidence in the ice time line, scientists will probe ancient atmospheric temperature by various methods, including measuring the ratio of 18O to 16O in the ice. Because of how temperature affects the relative condensation and evaporation of the isotopes, that ratio during ice ages is lower than between ice ages.

Scientists expect to learn about greenhouse gas concentrations and other atmospheric chemistry from the trapped air. “The gas levels are small, and the amount of ice available, particularly for the very oldest ice, will be extremely limited,” says Joel Pedro, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Tasmania and the lead scientist with Australia’s Million Year Ice Core project. “A lot of work is underway to drive down the sample size needed while maintaining high precision.”

“We extract the gases by melting or crushing the ice and use standard techniques” for analysis, including gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, and laser spectroscopy, says Christo Buizert, an Oregon State University assistant professor in Earth, ocean, and atmospheric sciences who coordinates COLDEX ice-core analysis efforts. Measurements of CO2, methane, and noble gases anywhere are globally representative because those gases are relatively long-lived in the atmosphere. By contrast, trapped particulates, including salt, dust, and volcanic materials, tend to reflect more local processes.

Dust in Antarctica comes mainly from the Patagonia desert. Levels are higher when it’s cold, dry, and windy and lower when the climate is wetter and stiller. “Dust is a proxy for humidity and windiness,” says Olaf Eisen, a glaciologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany. “You can learn a lot. That’s why it’s exciting.”

And more salt in the ice core may indicate more sea ice, Pedro says, because brine crystals, which form on the surface of sea ice, are lofted by winds and stored in the ice sheet. He notes that Australia is investing around Aus$45 million ($30 million) to revive skills for working in Antarctica. The country wants a seat at the table on the future of Antarctica, he says. “The politics is aligned with the big science objectives of recovering the oldest ice core. It has implications for Australia in terms of sea-level rise and climate.”

Measurements that give snapshots in time are already coming in from Allan Hills ice. Continuous records going back to the Mid-Pleistocene Transition could be available as early as 2025 from the Beyond EPICA team and toward the end of the decade from the other research teams.

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org