Philanthropies selectively mitigate damage from lost federal science funding

Since President Trump regained the White House in January 2025, cuts to and uncertainty about federal science funding have led to reductions in hiring for research; panic about paying students, postdocs, and technicians; the dissolution of projects; and scrambling for funds. As a result, science philanthropies are seeing increased demand for their resources. In response, they are creating programs to retain early-career researchers, continue threatened projects, and keep research directions open. But philanthropies caution that they can “fill gaps, not gulfs,” as Harvey Fineberg, retired president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, puts it.

What philanthropies can do best is “de-risk” research by funding ideas that may not work or that might not be funded by government or industry, says Cynthia Friend, president of the Kavli Foundation. “Researchers need a proof of principle before their work is viable for federal funding,” she says. At the Kavli Foundation, “we try to strategically fund research that has a potential for transformative impact.”

Philanthropic giving from foundations and other nonprofits accounted for about 15% of funding for US basic and applied research at universities and nonprofit research organizations in 2023, according to the most recent figures from the Science Philanthropy Alliance. In a survey it conducted last year, says Kate Lowry, the alliance’s strategy director, nearly 80% of the respondents said they were changing or considering changes to their grant making in response to shifts in federal science funding. For example, some philanthropies awarded extensions for current postdocs and graduate-student grant recipients.

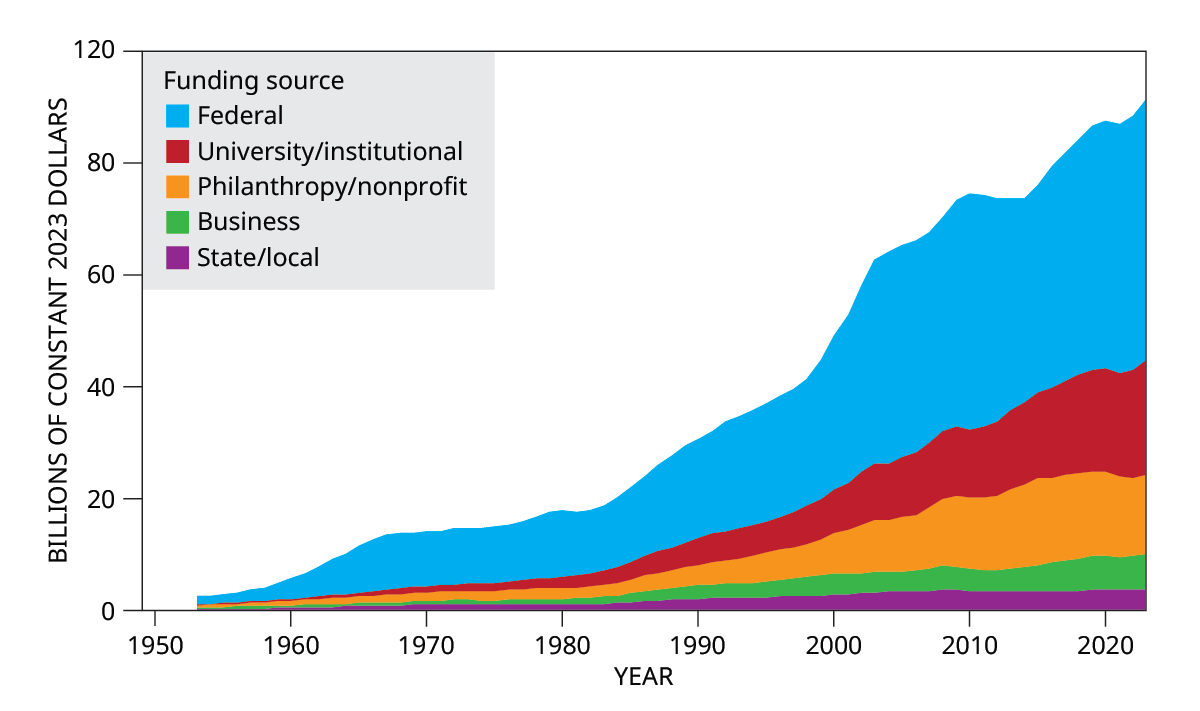

Funding for basic and applied research at US universities and research institutions reached nearly $115 billion in 2023, the most recent year for which data are available. About 15% of that was directly from philanthropic foundations and nonprofits; including legacy philanthropy, such as from university endowments, that number goes up to about 21%. Those and related data are available in an interactive format in the 2025 Science Philanthropy Indicators Report

(Data from NSF’s National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics; figure adapted from the 2025 Science Philanthropy Indicators Report.)

“Philanthropies have always been in the business of funding areas that others are not supporting,” says Fineberg. Typically, he says, they look for niche areas, specific needs, and frontier science. “In light of the current funding environment,” he continues, “every philanthropy that is involved in science has had to ask itself, Where do we invest?”

Helping younger generations

The biggest impact of the uncertainty in federal funding so far “is nervousness in the scientific community,” says Gregory Gabadadze, a professor at New York University and the Simons Foundation’s senior vice president for physics. The foundation, he says, saw a huge increase last fall in applications to all its programs in math and the physical sciences. “It’s not clear how to deal with that situation,” he says. “But the foundation leadership will allocate more funds than usual to support the best of them.”

In its new Simons Empire Faculty Fellowship program, the foundation is awarding research institutions in New York state a total of $45 million to hire 55 junior faculty into tenure-track positions in mathematics, physics, neuroscience, and ecology and evolution. The foundation will pay the new hires’ salaries for three years. The program is intended to thaw the hiring freezes adopted by many institutions. “That will help younger generations,” says Gabadadze. The foundation is also increasing the number of awards to collaborations and to well-established institutions that reach out to researchers from less-supported places. Those two programs are getting funding bumps of $30 million and $3.7 million, respectively. The Simons Foundation and the Simons Foundation International have a combined annual budget for math and physical sciences that fluctuates around $100 million, Gabadadze says.

Researchers convene at the University of Chicago in summer 2025 to work on ultraquantum matter, in a collaboration funded by the Simons Foundation and the Simons Foundation International. Applications to such philanthropy-funded activities are rising as US federal funding has become rockier.

(Photo by Ashvin Vishwanath, Harvard University.)

For its part, the Moore Foundation has boosted funding for early-career researchers. “We thought the postdoc period was important and vulnerable,” says Fineberg. The foundation set aside $55 million—of more than $210 million it spent on science in 2025—for some 400 postdoctoral researchers across 25 fields.

The University of Washington is among the 30 universities that are benefiting from the Moore Foundation’s support for postdocs. With a $2.5 million gift, “we ended up being able to provide funding for 16 postdoctoral fellows for periods of 9 to 24 months,” says Cecilia Giachelli, an associate vice provost at the university. “What is huge is that people can complete their projects. The postdoc is a key time for a researcher’s career stability. The money will help us retain them.”

Being catalytic

Smaller foundations are also adjusting their giving. Some are specifically funding areas, such as climate-change research and underrepresentation in science, that have been targeted by the Trump administration.

The Kavli Foundation is expanding a program it created in 2022 to help scientists whose research has been disrupted. For example, it has supported scientists from Ukraine who were displaced by Russia’s invasion of their country. Now, says Friend, the program is helping several US-based scientists whose work has been disrupted by funding interruptions. The number of fellowships, she says, is increasing from 5 to up to 20. The program, she adds, focuses on early-career scientists and “can help bridge to the future.”

The Research Corporation for Science Advancement tries to be “catalytic” with the $11 million it distributes annually, says Andrew Feig, a senior program director at the organization. In December, it gave a total of $800 000 to 11 current and past awardees who had lost funding or whose funding had been delayed. “We couldn’t put a finger in the dike for all of the need,” he says. “We triaged the applicants to see who had the most critical need and was experiencing meaningful disruption. We looked to see that they were making longer-term changes to meet the new funding norm.”

In mid-January, Congress passed a budget that is nearly flat—a far brighter outlook than Trump’s proposed budget, which would have cut funding for basic and applied research by 37%, according to estimates by the Science Philanthropy Alliance. Even so, research funding will change, says Feig. “If you are not in the pillars that the administration is interested in—critical materials, quantum information, AI—you had better be ready to pivot if you want to maintain funding,” he says. “Federal funding may be more tied to translational work that can quickly move into applications.”

“The goodwill of rich people”

“We are in a tight situation,” says Mark Raizen, an experimental physicist at the University of Texas at Austin, “and it’s clear that private foundations cannot pick up the slack.” Applying for federal money has become very frustrating in recent years, says Raizen, whose work on production and applications of isotopes is mostly funded by philanthropies. “Researchers write proposals and get rejections. It’s discouraging for young scientists.” Still, he notes, federal agencies will renew funding for good work, whereas “foundations don’t fund continuously: Once you have proven something, it’s not high risk anymore.”

“Researchers are looking more desperately for opportunities,” says David Kaplan, a theoretical physicist at Johns Hopkins University. He notes that he and his colleagues are lucky to have funding from Michael Bloomberg. But philanthropies and individual donors can be “idiosyncratic,” he says. Giorgio Gratta, an experimental physicist at Stanford University, says he appreciates the contributions of philanthropies and individual donors to science, but “going back to rely on the goodwill of rich people—like before World War II—seems like a step backwards for a nation that has been a trendsetter in funding fundamental science.”