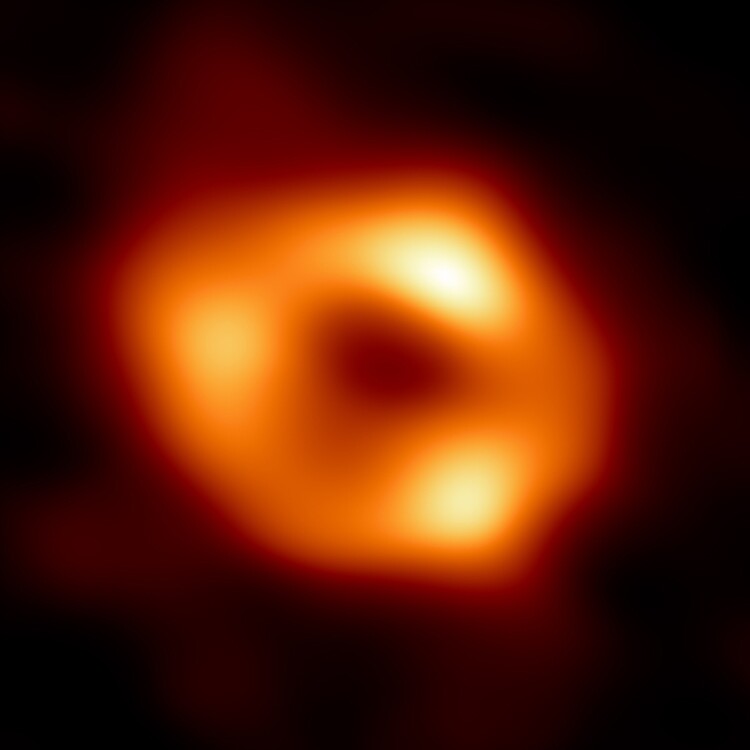

A portrait of the black hole at the heart of the Milky Way

A bright ring of plasma orbits Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

EHT collaboration

Three pandemic-dominated years after sharing a historic image of a black hole

If you think the blurry, toroidal figure looks familiar, that’s a good thing. Despite being three orders of magnitude closer than the galaxy Messier 87’s (M87’s) central black hole, which the EHT imaged in 2019, Sagittarius A* is also three orders less massive, so the angular sizes of the two black holes are very similar. And according to general relativity, the size of the shadow is determined only by the radius of the event horizon, which in turn is directly proportional to the black hole’s mass (see the Quick Study by Dimitrios Psaltis and Feryal Özel, Physics Today, April 2018, page 70

The images of both black holes are the culmination of analyzing data collected in April 2017 from eight millimeter-wavelength telescopes scattered all over the world. By time-stamping the measurements using atomic clocks installed at each observing site, researchers were able to combine the data using a technique called very-long-baseline interferometry to achieve resolution comparable to that of an Earth-size telescope. After calibrating the data and honing the imaging algorithms, the EHT team was able to turn the 2017 observations of M87* into four images resembling the final product by June 2018 (see “What it took to capture a black hole

The 10-meter South Pole Telescope at Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica was one of eight telescopes to observe Sagittarius A*.

Keith Vanderlinde

In many ways, M87* was the perfect first subject, says Dimitrios Psaltis, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona and a founding member of the EHT collaboration. Though located a sizable 55 million light-years away, the M87 galaxy has an orientation almost perpendicular to our galactic plane, which provides a relatively gas- and dust-free line of sight to the black-hole target. In contrast, capturing the shadow of Sagittarius A* requires looking inward from our vantage point within the disk of the Milky Way, straight into the crowded galactic center about 27 000 light-years away. Fluctuations in the free-electron density of the plasma located along the line of sight introduce phase variations in the microwaves destined for detection by the EHT. The result is a blurring of the source image.

The EHT researchers knew they would have to contend with that blurring, which is a major reason they chose to make observations at 1.3 mm rather than at larger wavelengths, which would scatter even more drastically. To further remove the effects of gas and dust, the team developed a model of the blurring effect and made separate observations with the EHT observatories to quantify various model parameters. In the end, Psaltis says, the impact of blurring was less than the team had feared.

A second complicating factor is Sagittarius A*'s size. If M87* were placed at the center of our solar system, its event horizon would be located somewhere near the Voyager 1 probe

Part of what allows the EHT telescope network to achieve such high resolution is that it captures its subject from different angles as Earth rotates, much like a computed tomography machine scans from multiple positions. In both cases, the subject (or patient) is assumed to be static. “The algorithms assume the thing you’re taking a picture of is fixed,” Psaltis says. “If it takes 10 hours to take a picture, M87* won’t change much, but for Sagittarius A* the plasma has already circled 50 times.” He and his colleagues were concerned that the black hole’s environment would be so dynamic that a long-exposure observation would never be able to achieve adequate resolution—and no model would be able to cancel out the effects. Fortunately for the EHT team, again the blurring was less than feared. “It turned out to be a gentler, more cooperative black hole than we had hoped for,” Özel said at the press conference.

The busy, dusty center of the Milky Way, which includes the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*, is captured in this 2009 photo taken on the mountain Cerro Paranal in Chile.

ESO/S. Guisard

After taking a break following the April 2019 release of the M87* results, the more-than-300-member team was just ramping up its Sagittarius A* work when the pandemic hit. Face-to-face meetings that had been vital for the imaging and modeling work on M87* were replaced with Zoom meetings among collaborators across the globe. “This is a big reason why it took three years instead of eight months,” Psaltis says.

The new image complements the knowledge scientists have obtained in recent years about the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole. For example, 2020 Nobel laureates Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel lead teams that have tracked the motion of stars orbiting perilously close to Sagittarius A* and have determined the black hole’s mass to a precision of about 1% (see Physics Today, December 2020, page 17

Editor’s note, 12 May: The article was updated with quotes from the Washington, DC, press conference and a description of the black hole’s orientation.

More about the authors

Andrew Grant, agrant@aip.org