Sand and mucus: A toolbox for animal survival

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.5137

Animals are under constant pressure to survive in their surrounding environment, and they have evolved countless strategies to adapt, colonize, and reproduce successfully in their habitats. 1 Almost acting as materials scientists, animals may directly manipulate complex fluids around them or secrete complex fluids themselves to fulfill a specific task. Mucus, for example, demonstrates a wide range of rheological properties depending on its physiological purpose—locomotion, sexual reproduction, protection against predators, or one of countless other uses. And when conditioned properly, sand present in the habitat can be used for movement or for predation.

ISTOCK.COM/ELENAMICHAYLOVA

Rheologically active materials—those with unusual or nonlinear responses to an applied force (stress) or deformation (strain)—often have clearly defined action windows, so matching the material properties with an animal’s desired outcome is essential. To exploit the rheological properties for the specific task, the animal therefore must sense and, if needed, manipulate the rheology of the surrounding complex fluids. Rheology and materials science provide a valuable approach to study materials originating from the habitat or secreted by an animal, with implications for biomimetic materials design and ethology.

Defining terms

Selective pressure on animals originates from the entire set of environmental factors acting on them. Those factors can be classified as biotic or abiotic. Biotic factors include all other organisms in an individual’s environment, the animal itself, and the resulting consequences, such as competition for food, space, or shelter. Abiotic factors include the chemical or physical nature of the surroundings, such as temperature, humidity, nutrients, and materials’ mechanical properties.

Animal–material interactions can be further distinguished by the material’s origin, whether endogenous (produced by the animal itself) or exogenous (provided by the habitat). 2 For example, endogenous abiotic material, such as the “net” of air bubbles a humpback whale blows to trap fish, originates from an animal but is not formed by a biological process. Exogenous biotic material is formed by a living organism but not by the animal that uses it later on: Cow dung, for instance, provides shelter and nutrients for insects and their larvae. Endogenous biotic material originates from the animal that also utilizes it; examples include saliva and mucus for digestion and lubrication.

Animal–material interactions also depend on a whether a material is hard or soft, as determined by its mechanical and rheological properties. Hard exogenous materials generally do not change much over time or as a function of applied mechanical stress, and thus they offer little physical response for animals to exploit. Fluids, on the other hand, do respond to external forces and often have fascinating material properties as a function of applied stress or strain as well as time and temperature.

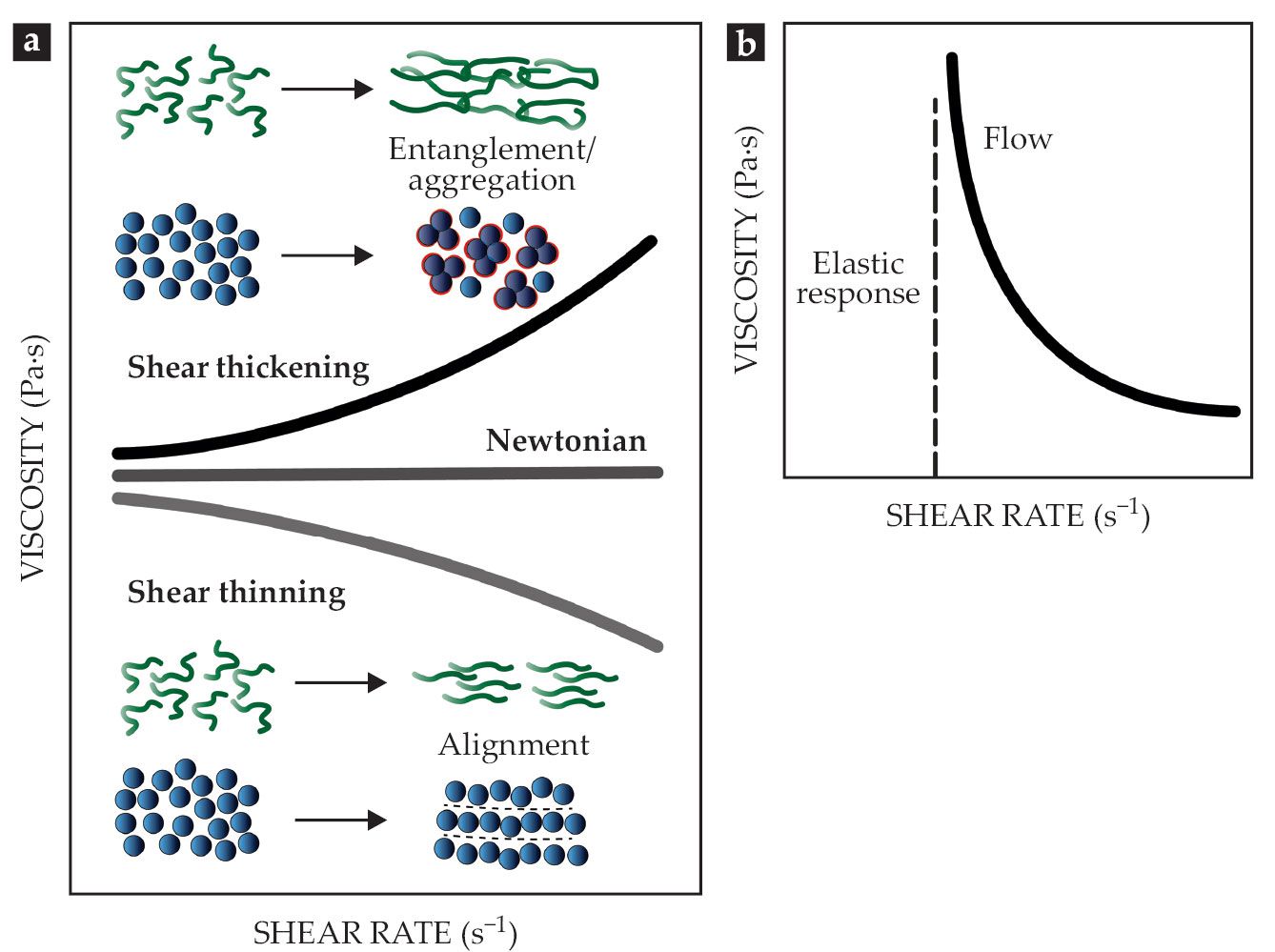

The simplest and most convenient way to describe the mechanical properties of fluid is by its viscosity, which expresses the internal friction during flow and deformation. For Newtonian or linear fluids, the viscosity is a constant, independent of the acting forces, as shown in figure

Figure 1.

Rheological properties of complex fluids. (a) For Newtonian fluids, the viscosity is independent of shear rate. Non-Newtonian fluids can be shear thinning or shear thickening. Such non-Newtonian flow properties arise from the alignment, orientation, or aggregation of structural elements such as mucin proteins and sand particles. (b) Yield-stress fluids will only begin to flow—with Newtonian or non-Newtonian behavior—once a minimum deformation or stress is applied. (Adapted from ref.

Shear-thickening and shear-thinning behaviors arise from the flow-induced orientation and alignment of the structural elements of the fluid, such as mucin proteins in mucus or suspended sand particles, as shown in figure

This article focuses on two very different complex fluids: sand, an exogenous abiotic material, and mucus, an endogenous biotic material. Both exhibit strain- and time-dependent flow behavior, which animals sense, manipulate, and use in their survival strategies. The mechanical and rheological properties of granular materials such as sand are mainly determined by the moisture content and the particle size distribution, shape, and roughness. The governing equations to describe the flow properties extend from frictional rheology, describing the interplay between inertial and viscous forces, to more classical suspension rheology.

Mucus is a collective term for substances with similar composition and properties; it appeared early in the evolution of multicellular animals and probably evolved multiple times independently. 4 It is composed of water, proteins, lipids, salts, and cellular debris and is constantly renewed by the secreting goblet cells of mucosal membranes. The main component, mucins, are proteins densely covered with covalently bound oligosaccharides (carbohydrates). Mucus is used for various well-targeted physiological applications, such as cell protection and food and gas uptake, and also for locomotion, defense, and predation, as discussed below. Mucus can fulfill those different tasks because of an almost endless combination of proteins and oligosaccharides, which determine the viscoelastic or gel-like properties of the physically cross-linked material. 5

Locomotion

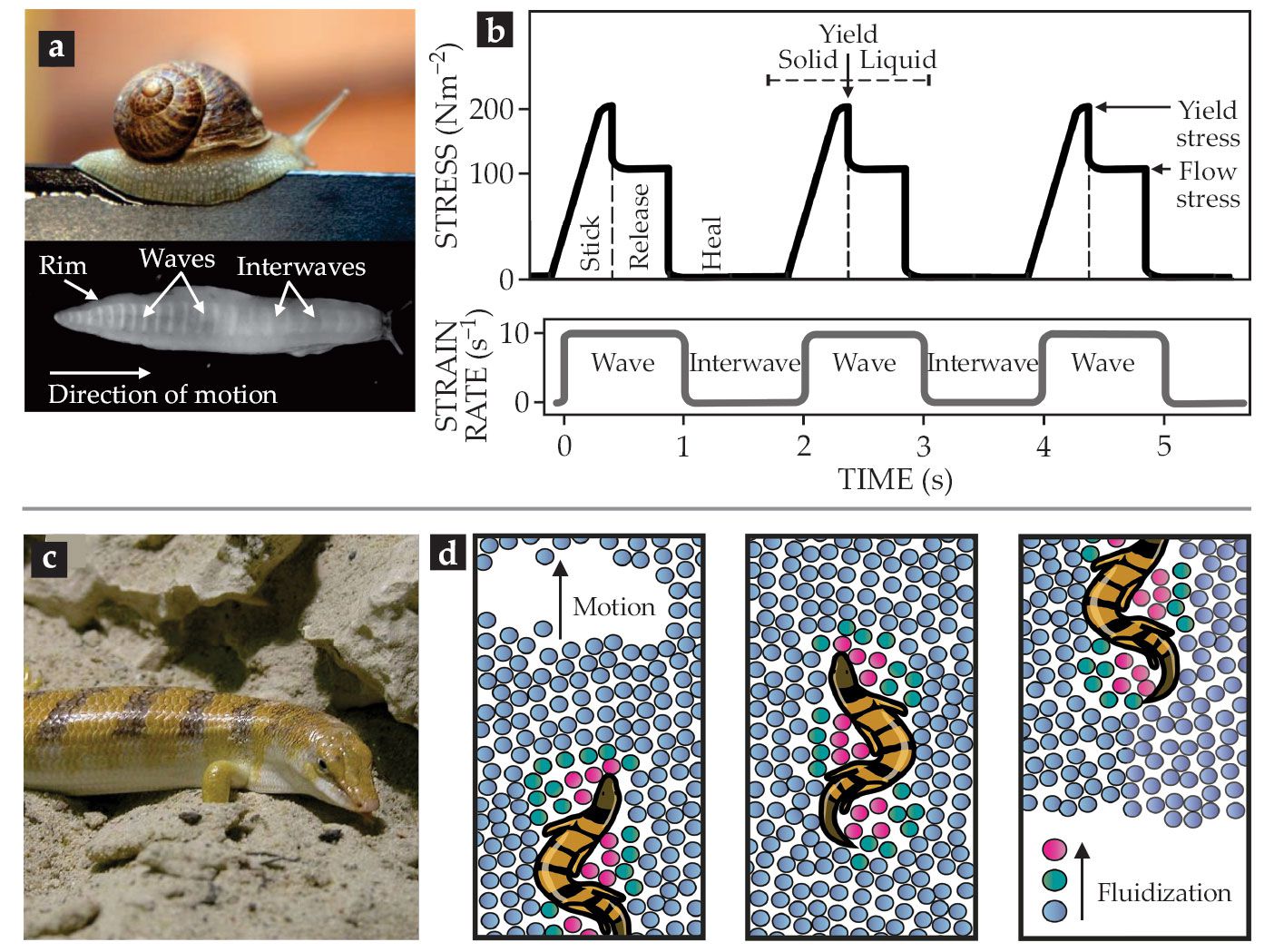

Terrestrial gastropods, such as snails and slugs, use their entire body as a single foot to crawl by so-called adhesive locomotion. The propulsion is powered by muscular waves that propagate from tail to head along the ventral side of the foot. The periodic contraction–relaxation waves (see figure

Figure 2.

Locomotion exploiting mucus and sand. (a) Slugs and snails move via traveling waves along their body that rely on the yield-stress and shear-thinning behavior of the viscoelastic mucus that the animals excrete. (b) The transient rheological properties of the pedal mucus of the Pacific banana slug (Ariolimax columbianus) during locomotion.

The mucus’s rheological properties must be threefold: a solid-like elasticity at low stresses (including at rest); a high, sharp yield point with a transition to a highly viscous, shear-thinning liquid; and a fast recovery of network structure after stress release. A movement cycle, as visualized in figure

Although adhesive locomotion is the most energy-intensive form of movement, the largest energy expense is mucus production, not muscle activity. Within the stick–slip cycle of resting and sliding, the transient rheological properties represent a fine-tuned interaction between the animal and its environment. The secreted mucus layer also provides adhesion, which allows the animal to climb walls and trees and crawl across ceilings and overhangs, and it enables a spectacular mating performance, as discussed below. But locomotion is significantly slowed down on rough surfaces or granular matter—not because of the surface properties per se but because of the increased amount of mucus required to lubricate the ground.

Some snakes and lizards that are native to semiarid or arid areas exhibit an exceptional way of locomotion: swimming-like movement. (See the Quick Study by Yang Ding, Chen Li, and Daniel Goldman, Physics Today, November 2013, page 68

In addition to their dependence on the packing fraction, the mechanical properties of granular media also change dramatically between dry and water-saturated conditions. As a consequence, rain in the desert renders the dry sand into a compact suspension that is much harder to shear, thereby temporarily stopping underground locomotion until the sand has dried up again. Granular flow is classically described by frictional rheology: In dry conditions, the macroscopic friction is characterized by the dimensionless inertial number (relating the inertia forces to the imposed shear forces), while in wet conditions, it is replaced with the dimensionless viscous number (relating shear forces to normal forces). Both dimensionless numbers are a function of the local solid packing fraction.

To “swim,” the sandfish locally fluidizes dry sand using undulating stresses (see figure

Catching prey

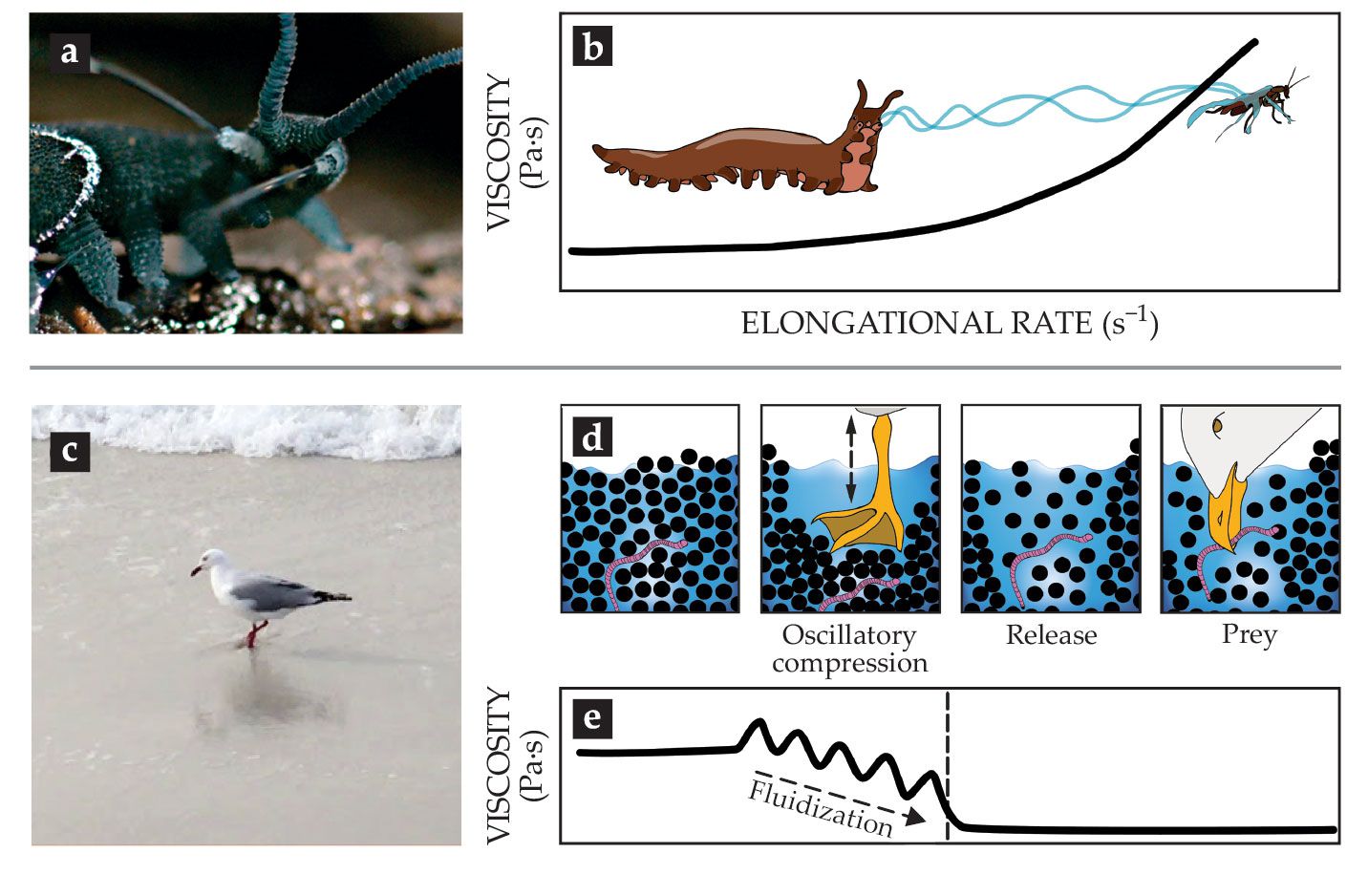

Velvet worms (phylum Onychophora) use an endogenous complex fluid that is strain hardening and adhesive to immobilize their prey.

10

The worms, which inhabit humid regions of the tropical and temperate zones and have lengths of 0.5–20 cm, crawl up on their prey and eject a sticky slime from two papillae flanking their mouth, as shown in figure

Figure 3.

Catching prey with the help of complex fluids. (a) Slime ejection from the slime papillae of a Euperipatoides rowelli velvet worm.

In contrast to other secreted adhesive fibers like spider or silkworm silk, which are solid upon excretion, velvet-worm slime is a remarkable showcase of a biological complex fluid with fine-tuned transient properties. Fluidlike in the slime glands and papillae, it develops cohesiveness and mechanical strength during the elongational flow upon ejection. The functional components of the aqueous slime (90% water by weight) are protein–lipid nanoglobules, which are about 50% protein and 1% lipid and exemplify the important role of additives in biological and biomimetic composite materials. The nanoglobules are approximately 150 nm in diameter and have a narrow size distribution. They are probably formed by the complex electrostatic aggregation of oppositely charged protein moieties. 11 Although the exact amino-acid sequence and the folding of the proteins is unknown, the proteins have a high molecular weight, high charge density, and some portion of β-sheet structures, which all favor intra- and intermolecular electrostatic interactions.

The transition from fluidlike slime to viscoelastic fibers upon extrusion outside the animal’s body suggests that elongational strain thickening is crucial for the slime’s functionality. That untested hypothesis is depicted in figure

The final slime filament consists of thin, elastic threads with several adhesive globules distributed along their length. Dried threads undergo a glass transition and reach a stiffness of about 4 GPa. Interestingly, the initial protein–lipid nanoglobules can be re-formed upon rehydration of the dried slime, and new fibers can be drawn from the regenerated slime. That behavior supports the current model, which says that noncovalent electrostatic interactions are responsible for slime formation and that the liquid–liquid phase separation into dispersed protein–lipid nanoglobules returns the slime to its equilibrium state.

Seagulls (family Laridae) and numerous plovers (family Charadriidae) in tidal zones use a two-footed pedaling technique (see figure

The pedaling, a form of oscillatory compression (see figure

Reproduction

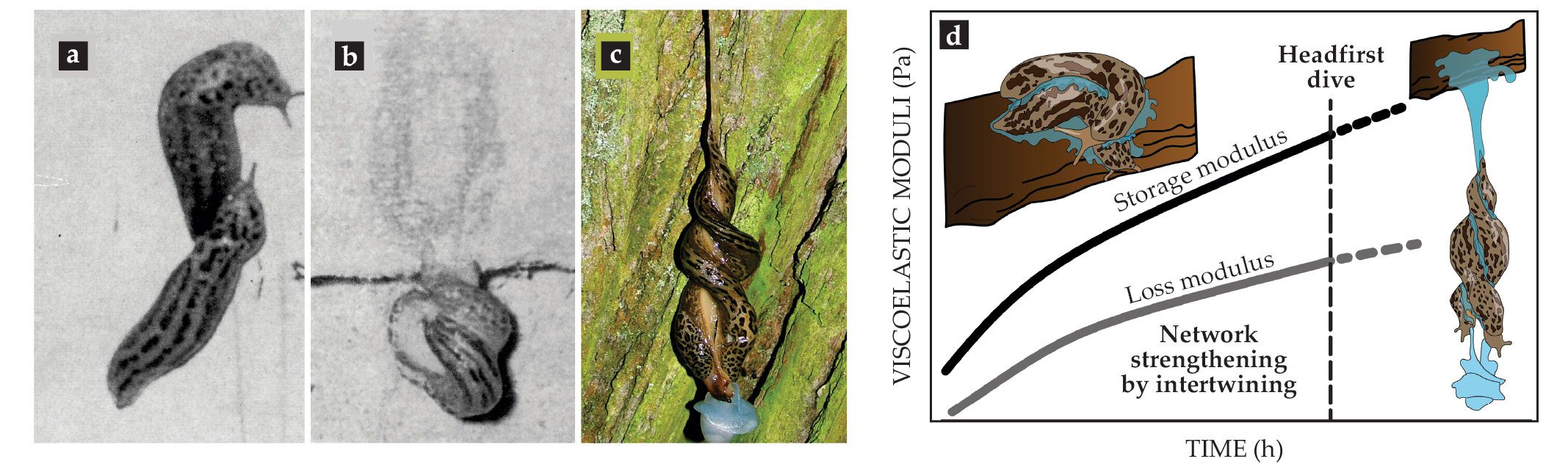

One of the most spectacular examples of using endogenous complex fluids is the mating ritual of leopard slugs (Limax maximus). Slug twosomes use a thread of gel- or rubber-like mucus to suspend themselves in midair to perform their circus-like sexual act (see figure

Figure 4.

Viscoelasticity in courtship. (a–c) After a leopard slug (Limax maximus) meets its mating partner, they intertwine and secrete mucus, which thickens to support a headfirst dive that allows hanging intercourse. (d) Hypothesized change in viscoelasticity as expressed by the storage modulus (elasticity) and loss modulus (viscosity) of leopard slug mucin over time during courtship and mating. (Adapted from ref.

Like other gastropods, leopard slugs usually use mucus for adhesive locomotion. But once a twosome reaches a desirable location, preferably the bottom side of a tree branch or even a wall, the slugs start to intertwine and stimulate the formation of a thick mucus layer around themselves. The mucus secretion and rubbing continue for up to an hour until the mucus achieves a gel- to rubber-like consistency. The slugs then dive headfirst from the supporting branch or wall, dangling by the mucus thread. The midair position allows full extension of male genitalia, a feat difficult to perform without being suspended.

Slugs and snails are known to produce mucus with different composition and rheological properties depending on its use. But for mating leopard slugs, the time-dependent change of the rheological properties is crucial. The yield stress and viscosity of salivary, nose, and slug mucus generally increase upon drying. And mucus viscosity scales as the cube of mucin concentration. But the transition from a viscoelastic fluid to a gel-like thread cannot be explained only by a higher concentration of mucin or other mucus components. The applied shear stresses induced by the constant intertwining could promote mucus elasticity through the formation of intermolecular bridges. That possibility is supported by the observation that shear forces cause mucin molecules to aggregate into larger network-like structures.

Before performing their slow-motion headfirst dive together, the slugs must somehow sense when the drying and intertwining have achieved the ideal gel-like mucus properties: Go too early and the thread will not hold the weight, and the slugs will crash-land in the bushes. Wait too long and the dried-out mucus will lose its gel-like properties and become solid, and again the slugs will not be able to exploit the viscoelasticity to safely lower themselves. As sketched in figure

Defense

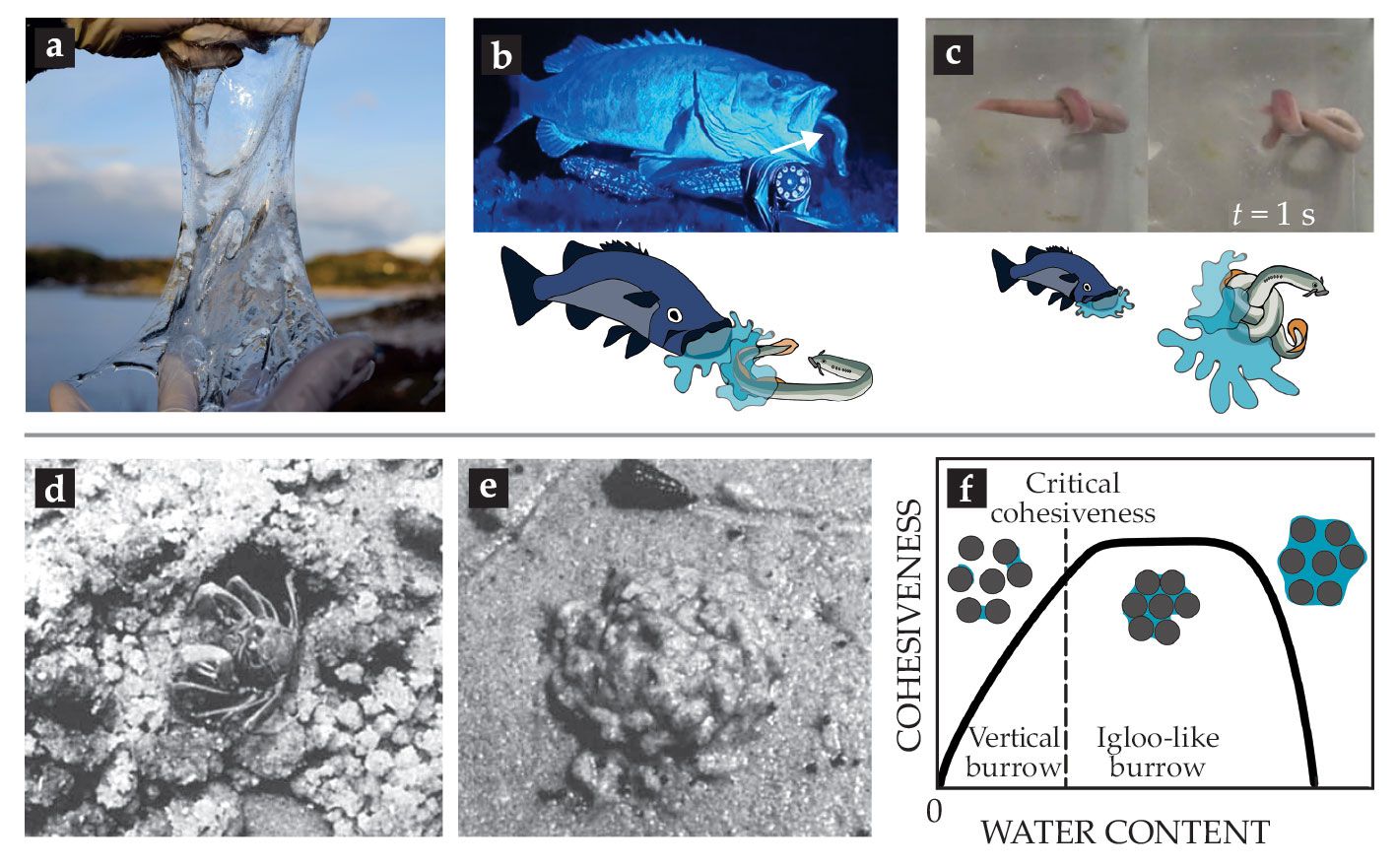

Hagfish (including Myxine glutinosa and Eptatretus stoutii) present a particularly striking example of an animal defense mechanism that uses complex viscoelastic fluids. The eellike animals play an important role in aquatic ecosystems: By burrowing and feeding on carcasses that sink to the seabed, they contribute significantly to substrate turnover and ocean cleanup. When hagfish are disturbed in their daily duty and attacked by predators, such as sharks or suction-feeding fish, they form huge amounts of slime in less than a few hundred milliseconds (see figure

Figure 5.

Defense and protection using complex materials. (a) Eellike hagfish (family Myxinidae) can form huge amounts of slime in a few hundred milliseconds. (b) The excreted slime clogs the mouth and gills of would-be predators.

LUCAS BÖNI

That remarkably fast slime formation is triggered by the release of a protein-based exudate from ventral glands into the surrounding seawater. Once in contact with seawater, the exudate rapidly forms a fibrous hydrogel that clogs a predator’s mouth and gills. 12 , 13 The exudate itself is composed of keratin-like protein threads, which are coiled up into microscopic balls called skeins, and mucin vesicles. In contact with seawater, the skeins unravel into long threads with lengths of up to 15 cm and form a wide-ranging network structure. The mucin vesicles, meanwhile, swell and eventually burst, releasing the water-absorbing mucin molecules into the network. 14

Hagfish slime thus can be considered a double network structure formed by the skein and mucin components. The long skein threads are crucial for the slime’s cohesion and viscoelasticity, whereas the mucins facilitate water entrapment. Both have their own mechanical and structural properties, such as elasticity and pore size. Together they form a soft yet elastic hydrogel with a water content higher than any other known biological hydrogel.

The rheology of hagfish slime is fine-tuned for its defense functionality. In extensional flow, such as the suction flow of suction-feeding fish, the mucin’s extensional viscosity increases by two orders of magnitude in just a second, making it harder for the predator to swallow and additionally clogging its gills (see figure

The notorious hagfish is not the only creature that uses slime to deter predators. When disturbed, the slime star (Pteraster tesselatus) presses water through mucus-lined channels to rapidly produce large quantities of mucus-based slime that engulfs it. 15 No rheological data are currently available on the slime, but it shows viscoelastic and transient rheological properties similar to those of hagfish slime. And the parrotfish (Chlorurus sordidus) secretes mucus during the night to form a gelatinous sleeping bag around its body to protect itself from parasites. In contrast to the instantly formed but short-lived slimes of hagfish and slime stars, parrotfish mucus is produced within one hour, and its protective function remains for up to five hours. 16 Although no rheological characterization of parrotfish mucus has been reported, it is described as gel-like or even solid-like, suggesting a higher solid content than other slimes.

Sand-dwelling crabs (genus Dotilla) use sand-based structures—either vertical burrows or igloo-like structures

17

(see figures

A versatile toolbox

Animals have generally little to no influence on the ambient conditions at which they exploit complex flow phenomena. As a consequence, some of the presented survival strategies are seen only in specific habitats. For example, the “swimming” locomotion in sand is only possible in arid or semiarid regions where sand can be locally fluidized with relatively small effort. On the other hand, the construction of complex sand formations is only possible in tidal zones where the water content makes sand cohesive—a strategy we humans also intuitively exploit when building sandcastles. Some animals, like the sand crabs, adapt their behavior depending on the surrounding material properties.

For endogenous complex fluids like those used by the velvet worm, the leopard slug, and the hagfish, ambient conditions such as temperature and humidity are not that critical for the initial performance. Instead, the imposed flow field—shear, elongation, or a combination thereof—triggers the fluid to fulfill its physiological task. An example is hagfish slime, which through a combination of shear- and ion-sensitive mucin vesicles and protein skeins manages to gel vast amounts of water instantly despite being expelled in a vast body of cold ocean water. After successfully deterring the predator, the slime eventually becomes diluted and dissolves in seawater—an important after-use behavior. The behaviors of both hagfish and velvet-worm slime are determined not by environmental cues but by the close relationship between the endogenous material’s chemical composition and the exerted flow profile that the material experiences during its employment. 18

The time scales on which complex fluids need to alter or retain their properties range from milliseconds to days. Many animals have developed materials during their evolution that allow for rapid change in fluid structure and properties. Hagfish slime is short-lived and dissolves rapidly in seawater after use, which helps the hagfish to escape from the slimy trap. On the other hand, the mucus-based cocoons of parrotfish remain stable for several hours in seawater to prevent parasite infestation during sleep. And the mating ritual of leopard slugs illustrates the importance of proper timing as material properties change.

Except for the velvet-worm nanoglobule extrudate, hagfish slime, and granular media, the rheological and structural properties of endogenous and exogenous complex materials under physiological conditions and usage by animals are relatively unknown. Differences in mucin composition are only well studied for humans and pigs, for example; for most other animals, such information is largely missing. How the choice and ratio of protein and oligosaccharide moieties and the overall solid content influence the rheological properties and stickiness of mucus remains to be studied for some of the examples discussed here. Furthermore, the motion of slugs shows that endogenous biotic material can rapidly cycle between a breaking state and a healing process. The rapid adaptation of those materials to the environmental condition suggests that phase transitions or concentration fluctuations govern the materials’ structural changes and resulting performance.

During evolution, animals found ways to use the rheology and structure of complex fluids to gain advantage and increase their Darwinian fitness. Studying the interactions from soft-matter, materials-science, and rheological points of view can help in understanding animal behavior, yield new insights for mimicking biomaterials, and provide a quantitative approach to ethology.

This article is a shortened adaption of “Complex fluids in animal survival strategies,” by Patrick A. Rühs, Jotam Bergfreund, Pascal Bertsch, Stefan J. Gstöhl, and Peter Fischer,

References

1. J. M. Smith, The Theory of Evolution, Canto ed., Cambridge U. Press (1993).

2. R. A. Campbell, M. N. Dean, Integr. Comp. Biol. 59, 1629 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icz134

4. T. Lang, G. C. Hansson, T. Samuelsson, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16209 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705984104

5. P. Fischer, in Recent Advances in Rheology: Theory, Biorheology, Suspension, and Interfacial Rheology, D. De Kee, A. Ramachandran, eds., AIP Publishing (2022), chap. 3.

6. M. Denny, Nature 285, 160 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1038/285160a0

7. J. H. Lai, J. C. del Alamo, J. Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J. C. Lasheras, J. Exp. Biol. 213, 3920 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.046706

8. A. E. Hosoi, D. I. Goldman, Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 47, 431 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-010313-141324

9. R. D. Maladen, Y. Ding, C. Li, D. I. Goldman, Science 325, 314 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172490

10. A. Baer, S. Schmidt, S. Haensch, M. Eder, G. Mayer, M. J. Harrington, Nat. Commun. 8, 974 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01142-x

11. A. Baer, S. Hänsch, G. Mayer, M. J. Harrington, S. Schmidt, Biomacromolecules 19, 4034 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.8b01017

12. V. Zintzen, C. D. Roberts, M. J. Anderson, A. L. Stewart, C. D. Struthers, E. S. Harvey, Sci. Rep. 1, 131 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00131

13. L. Böni, P. Fischer, L. Böcker, S. Kuster, P. A. Rühs, Sci. Rep. 6, 30371 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30371

14. J. E. Herr, T. M. Winegard, M. J. O’Donnell, P. H. Yancey, D. S. Fudge, J. Exp. Biol. 213, 1092 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.038992

15. J. M. Nance, L. F. Braithwaite, J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 40, 259 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(79)90055-8

16. A. S. Grutter, J. G. Rumney, T. Sinclair-Taylor, P. Waldie, C. E. Franklin, Biol. Lett. 7, 292 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2010.0916

17. S. Takeda, M. Matsumasa, H.-S. Yong, M. Murai, J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 198, 237 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(96)00007-X

18. M. A. Meyers, P.-Y. Chen, M. I. Lopez, Y. Seki, A. Y. M. Lin, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 4, 626 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2010.08.005

More about the authors

Peter Fischer heads the Institute of Food, Nutrition, and Health at ETH Zürich in Switzerland. His research focuses on rheology and structure of complex fluids.