How the blue-ringed octopus flashes its rings

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.5146

Shown in figure

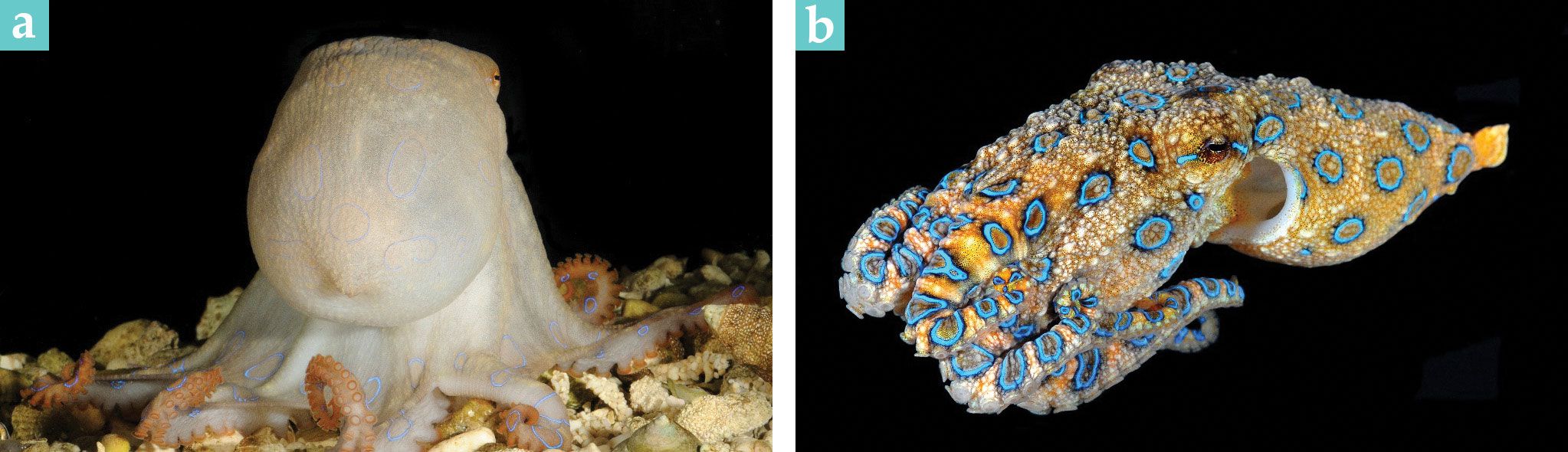

Figure 1.

A blue-ringed octopus, roughly 6 cm in length, is shown (a) camouflaged and (b) flashing its rings. (Courtesy of Roy Caldwell, University of California, Berkeley.)

Cephalopods, who spend much of their time hidden, are well known for their instant camouflage. Yet within the blink of an eye, the animals can change their appearance to be stunningly bright and colorful. Blue-ringed octopuses are no exception. When threatened, they quickly expose their blue rings in a series of bright flashes. Those flashes are an example of aposematism, a warning intended to deter predators. But unlike other aposematic animals, such as poison dart frogs, which permanently display their bright colors, blue-ringed octopuses hide their rings most of the time and only show them when necessary.

Skin reflectors

Optical physicists and materials scientists, particularly those working in the field of biomimetics, are interested in those displays for a number of reasons. One is that no energy is required to illuminate the animals’ rings; the process of making the rings visible is entirely passive. Indeed, all cephalopods reflect parts of the ambient electromagnetic spectrum from specialized structures in their skin. That reflectivity spans not only the visible part of the spectrum, but also near-UV and near-IR light. Another reason is that the displays are not always static. Some cephalopods have the additional ability to fine-tune the spectrum of their skin colors and change the reflected wavelength in a matter of seconds.

The skin of cephalopods is equipped with thousands—and in some species millions—of neurally controlled pigmented chromatophores. They are considered organs, each containing a sac filled with either dark brown, black, red, or yellow pigments. Attached to the pigment sac are several radial muscle fibers that are directly innervated by the brain. Contracting those muscles expands the sac and exposes the pigment. Relaxing them has the opposite effect: It causes the sac to retract into a tiny round ball. To appreciate how a chromatophore changes color, think of a partially inflated party balloon. Flattening the balloon with a glass plate would be analogous to muscle contraction, which exposes the pigment sac by pulling it into a thin disk; lifting the glass plate would relax the muscle and prompt the sac to retract and take on its normal round shape.

In addition to chromatophores, cephalopods generally have two types of structural reflectors. Leucophores are broadband reflectors responsible for creating white spots and lines in cuttlefish, octopuses, and some squid. By contrast, iridophores are cells made up of multilayered stacks of reflector plates consisting of a protein interspersed by spaces of cytoplasm—each plate differing in refractive index. The scattering of light in those stacks produces constructive interference.

Constructive interference

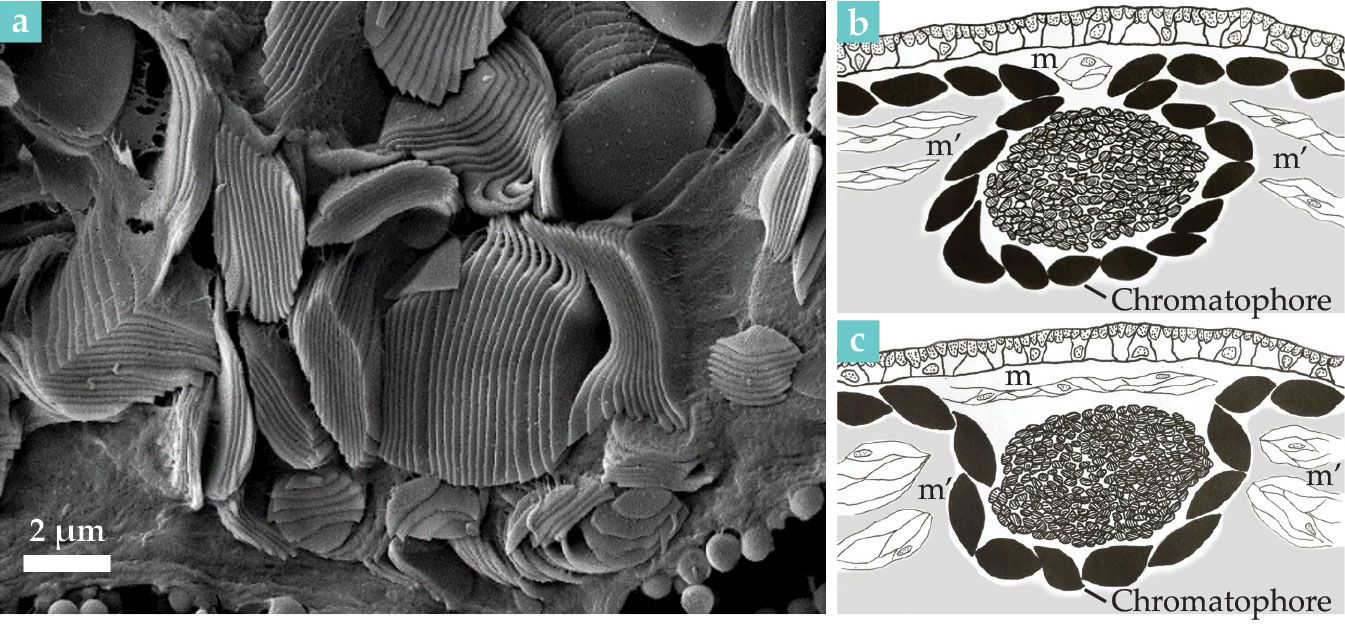

The iridophores inside the rings of the blue-ringed octopus contain a large number—as many as 30 in some cells—of those densely packed plates. All plates have roughly the same thickness (around 62 nm, as shown in figure

Figure 2.

Blue-ring iridophores are shown (a) as a parallel arrangement of plates in this scanning electron micrograph. (b) In a closed ring, contraction of transverse muscles (m), located above the iridophores (central round structure), covers iridescence. (c) Relaxation of those muscles, combined with contraction of muscles around the perimeter (m’), exposes iridescence. The sketches in panels b and c illustrate the rings’ flashing mechanism. (Adapted from L. M. Mäthger et al., J. Exp. Biol. 215, 3752, 2012, doi:10.1242/jeb.076869

The wavelength that they most strongly reflect equals 4nd, where n is the refractive index of the plate and d is its thickness. Assuming a refractive index of 1.59 and 20% tissue shrinkage—introduced by the processing required for electron microscopy—plates would reflect at 499 nm.

Because individual stacks are arranged at multiple angles in the skin, the iridescence is visible from a wide range of viewing angles. The arrangement is important because once the animal is threatened, the flashing rings need to be visible all around it.

How does the blue-ringed octopus show its blue rings when needed? It turns out that the rings contain physiologically inert iridophore cells, arranged to reflect blue-green light in a broad viewing direction. Dark pigmented chromatophores are located beneath and around each ring to enhance visual contrast. There are no pigmented chromatophores above the ring. That’s an unusual feature for cephalopods, which typically use chromatophores to cover or spectrally modify iridescence. But their absence holds the key to how the rings are flashed.

Surrounding the iridescent rings are muscle fibers that, as shown in figure

Lessons from cephalopod color change

Every cephalopod species is different, and not every color change method is found in every species. All cephalopods have pigmented chromatophores, and most species have many thousands in their skin. The structural reflectors, which are usually located in a layer beneath the chromatophores, can be tuned in some species—in many squids, for example—via specialized neurotransmitter receptors. They can also be tuned by the action of the chromatophores themselves, which indirectly block or spectrally filter the iridescence.

Although tuning the iridescence physiologically takes seconds to minutes, presumably because of changes to the physical state required to enable the optical changes, spectral change via chromatophores is much faster because the surrounding muscles are under direct neural control and muscle contraction is almost instant.

But cephalopod chromatophore pigments generally reflect longer-wavelength colors, such as reds, oranges, and yellows, which alone are insufficient to create high-contrast patterns. Those longer-wavelength colors are comparatively ineffective for underwater communication—at least at greater depths—where long-wavelength photons are quickly absorbed. Adding greens and blues to the signaling repertoire is paramount to creating a conspicuous visual signal, and using specialized reflector cells, cephalopods have mastered the challenge beautifully.

Of course, camouflage is still the most important survival strategy for cephalopods, so the brightly iridescent signals need to be obscured most of the time. While some species physiologically turn their iridescence off, which takes time, the blue-ringed octopus has found a way for its conspicuous warning signal to be available almost instantly, by contracting a specific set of muscles and moving the skin folds that hide the rings out of the way. When the danger is gone, those muscles relax, and another set of muscles contracts, pulling the iridescent rings back into their specialized skin pouches.

The color-changing mechanism described here, whereby highly reflective iridophores are hidden inside specialized skin folds, has not been found in any other cephalopod—or in any other animal for that matter. The uniqueness is mysterious, but it is a reminder that the natural world is highly complex and there is still much to learn. Octopus skin is extremely elastic and muscular, lending the animal the ability to give its skin three-dimensional texture, which is particularly useful for camouflaging on visually diverse underwater backgrounds. Given the dense network of muscles and nerves in their skin, it is perhaps not too difficult to imagine how the conspicuous flashing may have evolved in blue-ringed octopuses.

References

► R. T. Hanlon, J. B. Messenger, Cephalopod Behaviour, 2nd ed., Cambridge U. Press (2018).

► R. M. Kramer, W. J. Crookes-Goodson, R. R. Naik, “The self-organizing properties of squid reflectin protein,” Nat. Mater. 6, 533 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat1930

► L. M. Mäthger et al., [[QMechanisms and behavioural functions of structural coloration in cephalopods, ” J. R. Soc. Interface 6, 149 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2008.0311

► L. M. Mäthger et al., “How does the blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata) flash its blue rings?,” J. Exp. Biol. 215, 3752 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.076869

► L. M. Mäthger et al., “Bright white scattering from protein spheres in color changing, flexible cuttlefish skin,” Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 3980 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201203705

More about the authors

Lydia Mäthger is a biologist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.