A radio telescope array takes shape with private funds

DOI: 10.1063/pt.csfo.gvvj

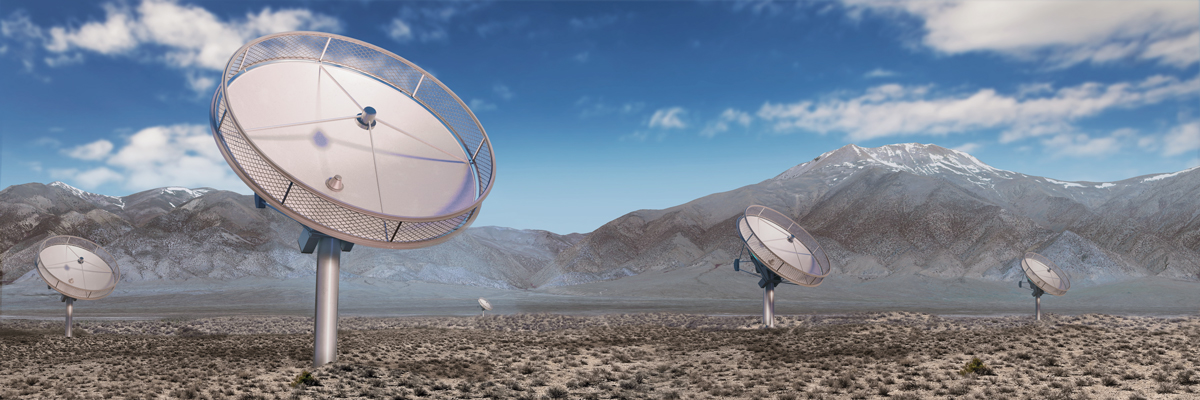

The design for the Deep Synoptic Array-2000 calls for 2000 steerable 5-meter-diameter radio dishes placed across 285 square kilometers in a Nevada valley. (Illustration by Chuck Carter/DSA team.)

Along a stretch of Highway 50 in Nevada that’s often called the loneliest road in America sits the town of Ely. And an hour drive from that remote site is an even remoter one called Spring Valley. There, if all goes as planned, scientists will begin construction in about a year on a radio telescope currently called the Deep Synoptic Array-2000.

The DSA-2000, in its current conception, is to be composed of 2000 5-meter antennas that work together as one to observe fast radio bursts, pulsars, and other radio-emitting objects with high resolution and sensitivity. Unlike traditional radio interferometers, which require computationally heavy analyses to compile observations, the DSA-2000 should be able to spit out images of the sky in real time.

Led by Caltech, the DSA-2000 team has used NSF funding to support two pathfinder projects, and it has expressed hope that the federal government will someday fund the estimated $10 million annual cost to operate the facility. But so far, the concept development for the DSA-2000 has been supported with funding from the philanthropy Schmidt Sciences and with in-house expertise from Caltech. The private money has allowed the radio array to go from idea to almost reality faster than have telescopes that rely on what has become an increasingly uncertain federal allocation process.

Envisioning a radio camera

The motivation for building a radio interferometer is that a network of identical antennas can achieve comparable resolution to that of a single gigantic dish and provide a wider field of view. But that convenience comes at the cost of sensitivity: Several dozen small antennas don’t have nearly the same photon-collecting area as the gigantic dish and thus can’t spot dimmer, more distant radio sources.

The idea for a deep synoptic array hatched around 2013. It would eventually be enabled by technology developed by Caltech radio astronomy engineers, particularly low-cost fiber that could transfer lots of data quickly and relatively inexpensive antennas whose electronics didn’t need to be cryogenically cooled. In successive years, researchers began to envision the development of a radio array with thousands of small antennas rather than dozens. An array with that much surface area would have both high resolution and high sensitivity.

“One of the main drivers was to really replicate Arecibo’s sensitivity but allow steering over the whole sky,” says Vikram Ravi, a Caltech astronomer and the telescope’s co-principal investigator, referencing the collapsed telescope in Puerto Rico. With $6.3 million of funding from NSF, the Caltech team made a prototype instrument called the DSA-110, which began operations in 2023.

But large-scale antenna cloning creates another problem: The amount of data scales as the number of antennas squared, says Gregg Hallinan, a Caltech astronomer who is the principal investigator of the DSA-2000. After the data come in, they have to be correlated so that researchers can piece together an image using the collected photons and estimates of the photons that arrived between the antennas. “Because the telescopes measure only a fraction of the incoming signal, we have to use nonlinear techniques to recover, or interpolate, the missing information,” says Hallinan.

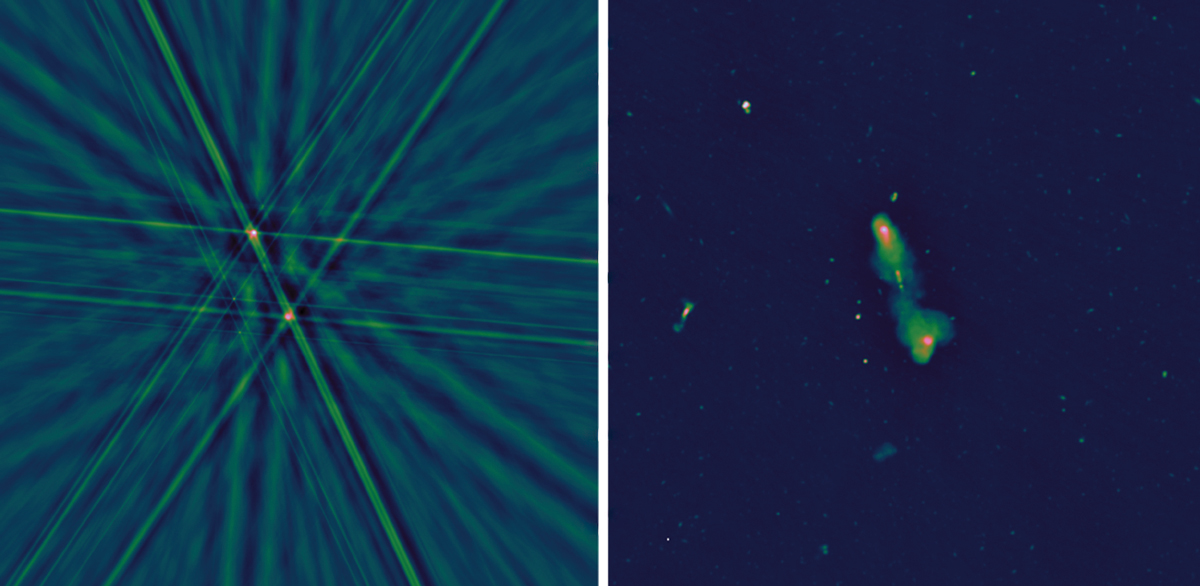

A radio camera. At facilities such as the Very Large Array in New Mexico, raw data (simulated at left) need significant processing to generate useful images. In contrast, the raw data collected by the Deep Synoptic Array-2000 (simulated at right) would require less processing, and images would be generated in real time. (Images from the DSA team.)

Buying drives to store data for processing would break the bank. But what if the Caltech researchers didn’t have to store all the data? What if they planned their telescope so that its antennas were densely packed enough to closely approximate a single dish? “The number of antennas is large enough that all of the different spatial scales in the image are basically recovered,” Hallinan says. If the researchers could make the aggregate smooth enough, they could use a digital back end to process and calibrate the data in real time to create images using computers with graphics processing units, the same kinds of chips that are often used in AI.

And so the team set out to make the DSA-2000 not a traditional interferometer but a radio camera. An NSF grant for an expansion of the Long Wavelength Array at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory was awarded in 2019. The facility helped prototype some of the snapshot technology.

Private contributions

Around that time, Stuart Feldman, currently the president of Schmidt Sciences, visited Caltech. He was seeking opportunities to invest in science projects that could both happen on fast timelines and potentially result in breakthrough technologies that could decrease the cost of future instruments. Schmidt Sciences was also interested in bringing technology from other disciplines into astronomy. “It’s not unlike the startup approach to development in industry,” says Hallinan.

By January 2020, Schmidt Sciences was funding an early version of the project. The organization went on to fund the DSA-2000’s design, to the tune of about $15 million, and other technology that would be part of the instrument, like the steerable antennas featuring no-cooling-required electronics.

On a timeline that outpaces those for many major science facilities, the DSA-2000 team is planning to start construction in around a year, in Spring Valley if the final environmental assessments permit the project to move forward there. The construction costs are estimated to be around $200 million.

David Kaplan, a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, says part of the DSA-2000’s quickness comes from its main institutional affiliation: Caltech is wealthy, and the project is led by the head of its radio observatory. “He has a lot of technical expertise on staff—people who understand every part of a radio telescope, from the foundation to the data analysis,” Kaplan says of Hallinan. He can tap them and hire additional experts with the Schmidt Sciences money.

Although the project’s prototype technology received NSF money, the team has not had to wait on federal funding cycles to progress to the main project; combined with the startup-style approach, that disentanglement from federal funding has enabled the project to move more quickly than traditional government-reliant projects. The next-generation Very Large Array, for instance, would complement the DSA-2000, but the project doesn’t yet have solid NSF funding despite being in the works for years. Construction on the estimated $3.2 billion project won’t start until late this decade at the earliest.

“We can tailor things like reviews and funding cycles to fit the project needs rather than have an overarching umbrella process that everybody has to go through,” says Arpita Roy, director of Schmidt Sciences’ Astrophysics & Space Institute.

The NSF-funded Deep Synoptic Array-110 at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory in California began operations in 2023. (Photo by Vikram Ravi/DSA team.)

The funding model for the DSA-2000 is also notable given the federal government’s recent attempts to cut the budgets and staff of science-funding agencies, including NSF, the largest funder of US ground-based astronomical research. The DSA-2000 has evaded some of that uncertainty, although the group hopes that NSF will fund the telescope’s operation and still needs to finalize the funding for construction.

Victoria Kaspi, an astrophysicist at McGill University who is not affiliated with the project, notes that Caltech has a long history of projects enabled by private funding, like the Space Solar Power Project. “It would be wonderful to have this be replicable for other projects, since providing resources for the very best science would have the highest impact,” she says. But given the necessary special sauce of variables—money, access, and expertise on staff—it could be difficult for other institutions to follow suit.

Looking ahead

With the promise of the DSA-2000 going into action sooner rather than later, collaborators have signed on from national observatories and universities. The DSA-2000 team is considering making the telescope’s data freely available immediately, in contrast to most observatories’ data, which have a proprietary period.

Kaplan stands to benefit from the DSA-2000’s science. He’s a member of the NANOGrav (North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves) collaboration, which uses a net of pulsars tracked by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Green Bank Telescope and other facilities to search for gravitational waves. The DSA-2000 team is discussing a collaboration with NANOGrav that would commit some of the facility’s observing time to timing pulsars.

The bulk of observing time, however, will go to surveys. “Every radio telescope ever built has detected about 10 million sources,” says Hallinan. “We’ll double that in the first 24 hours.” By imaging the entire sky many times over five years of operation, the array should detect more than 1 billion radio sources, he says. Complementing other next-generation telescopes, the DSA-2000 will pinpoint radio counterparts to sources found at other wavelengths with the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, SPHEREx, and others.

With high time resolution, the DSA-2000 should also detect thousands of transient sources. “I think the DSA-2000 is a very exciting project,” says Kaspi. “It is likely to have significant impact on understanding fast radio bursts.” The observations could also help probe dark matter and galaxy evolution by tracing neutral hydrogen gas.

The DSA-2000’s first prototype antennas are now set up at Caltech’s Owens Valley Radio Observatory. Says Ravi, “We’re very excited to be using them and starting to shake them out and making sure that they do what they need to do.”

This article was originally published online on 15 August 2025.

Editor’s note, 20 August 2025: This article was updated to clarify the state of the DSA-2000 team’s data-availability plans and its possible collaboration with NANOGrav.