Newton’s “force” and fake doors: The “geometric spirit” in the arts

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.5228

The science of Isaac Newton became a major part of the larger intellectual milieu during the long 18th century. Newton’s influence dominated all areas of human concerns—scientific and otherwise—as scientific principles were applied to all aspects of life in the Enlightenment. 1 “The geometrical spirit is not so tied to geometry that it cannot be detached from it and transported to other branches of knowledge,” proclaimed the French polymath Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle 2 in 1699. This “century of lights” could just as well have been called “the century of Newton”: The poet Alexander Pope once wrote in an epitaph for him, “God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.”

The Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain. (Courtesy of Emilio J. Rodríguez Posada, CC BY-SA 2.0

The art of the 18th century reflects a renewed interest in classical form with Newtonian symmetry and balance, an emphasis that earned the period the name neoclassicism. 3 That classical revival, which followed on the heels of the French and English Baroque period, began in the second half of the century and extended well into the following century. The period saw a transition from the fanciful, overdecorated ornamentation of the Baroque to the unpretentious, balanced style of neoclassicism—in which the emphasis was on symmetry and the pureness of form. In the UK, that classical revival was marked by the metamorphosis of highly ornamented Stuart architecture into reasoned, properly proportioned styles and Palladian supersymmetry. In an age rebelling against excess, Cartesian swirls yielded to Newtonian balance and simplicity.

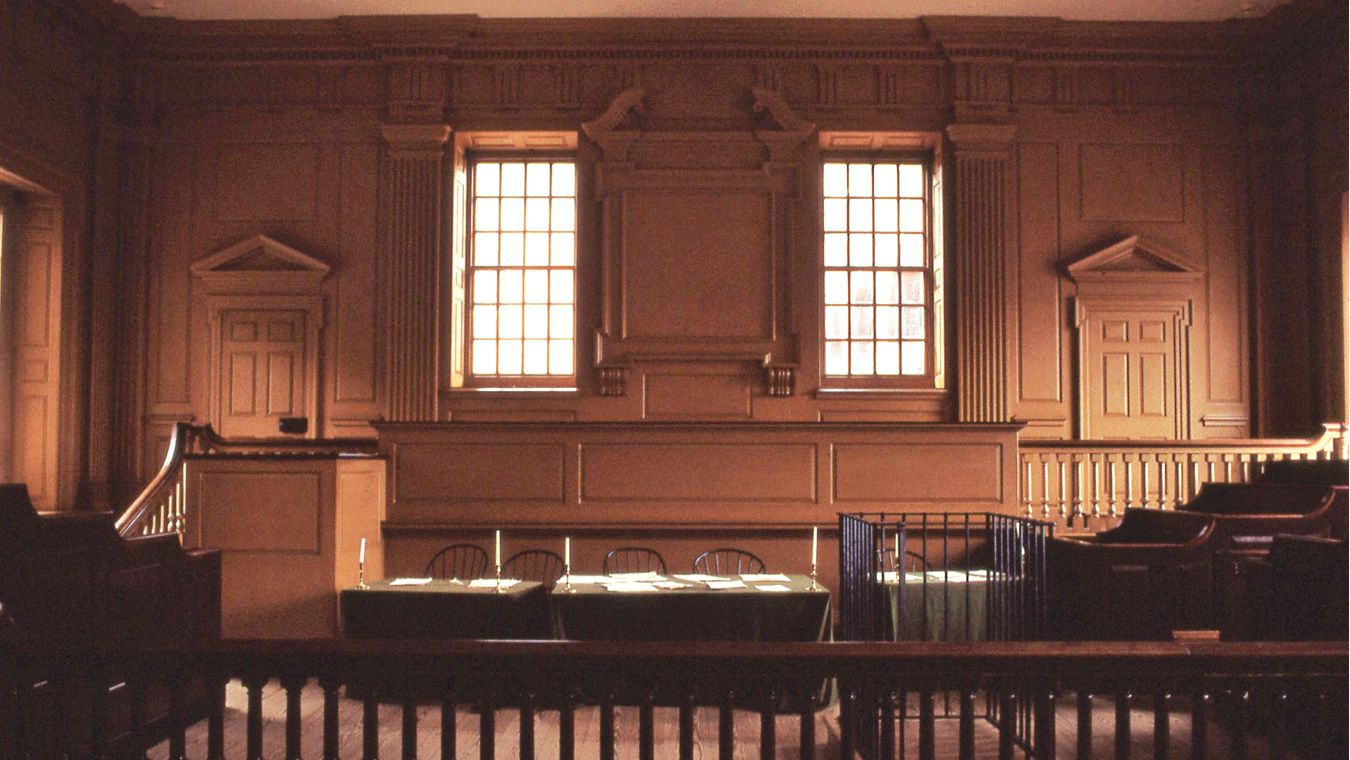

The old Pennsylvania Supreme Court Chamber in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall.

ROBERT FLECK

Newtonian neoclassical balance is evident in several monumental buildings of the period, which display on a rather ostentatious scale the century’s vogue for mathematical regularity in architecture. Examples include Vienna’s Schönbrunn Palace, remodeled in neoclassical style starting in 1743; the Circus, a ring of townhouses built beginning in 1754 in Bath, England; and Madrid’s Prado Museum (see page 11), designed in 1785.

Lesser known is the interior of the old Pennsylvania Supreme Court Chamber, which I photographed when I visited Philadelphia’s Independence Hall (see above)—itself a building symmetrical and balanced in design, like much of Georgian colonial architecture. Here, the door on the left is real and functional; the one on the right, however, is fake: It is inoperable, but necessary to preserve the overall symmetry of the room. The English architect-scientist and Newton contemporary Christopher Wren declared that “the geometrical is the most essential part of architecture.” 4

While connections between science and the cultural expressions of society are interesting in and of themselves, appreciating them helps bridge the science–humanities “two cultures” divide. As emphasized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, science literacy “includes seeing the scientific endeavor in the light of cultural and intellectual history.’’ 5 Recognizing that relationship enhances and enlivens education in and awareness of STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics) and, at the very least, helps humanize science.

References

1. J. H. Randall Jr, The Making of the Modern Mind: A Survey of the Intellectual Background of the Present Age, 50th anniversary ed., Columbia U. Press (1976).

2. H. Butterfield, The Origins of Modern Science 1300–1800, rev. ed., Free Press (1965), p. 185.

3. H. W. Janson, History of Art, 3rd ed., Prentice-Hall (1986), p. 574.

4. M. Kemp, Nature 447, 1058 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/4471058a

5. American Association for the Advancement of Science, Project 2061, Science for All Americans Summary, AAAS (1995).

More about the authors

Robert Fleck, (fleckr@erau.edu) Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Daytona Beach, Florida.