Early debates in space science

DOI: 10.1063/pt.ecmu.lpmo

Engineers working on Voyager 2 in 1977. (Image from NASA/JPL-Caltech.)

As the space age dawned at the end of World War II, the list of open questions in space science was vast. What was the source of the charged particles that caused auroras? How were those charged particles able to penetrate Earth’s magnetic field? What was the nature of the Moon’s surface? Those were but a few of the mysteries that remained unresolved in part because observations up to then had all been made from Earth.

Starting in the 1960s and 1970s, probes launched by the US and the Soviet Union helped to bring about a sea change in our understanding of our solar system, galaxy, and universe. The new phenomena detected by those probes forced scientists to refine their astrophysical models or develop entirely new ones. As new data poured in, physicists and astronomers often spent extended periods of time engaged in spirited debate as to which explanatory model was correct.

This article examines five significant debates in the early history of space science that helped shape our current view of the universe.

The solar wind

Observations of comet tails led German astronomer Ludwig Biermann to hypothesize in 1951 that a continuous flow of particles emanated from the Sun. His work attracted the attention of Eugene Parker (see figure

Figure 1.

Astrophysicist Eugene Parker, pictured in front of a blackboard. (Photo from the University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-11096, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.)

One of Parker’s colleagues at the University of Chicago, Joseph Chamberlain, made an alternate proposal in 1960. He theorized that the flow of plasma from the Sun was due to the evaporation of ionized particles from the hot solar corona. 2 Chamberlain’s mathematical model resulted in what he called a solar breeze, because the plasma would move considerably more slowly than Parker’s proposed solar wind.

In subsequent papers addressing each other’s hypotheses, Parker and Chamberlain modified their models. Parker generalized his to show that there was only one physically reasonable solution to his hydrodynamic flow equations, one that resulted in a high-velocity solar wind. Chamberlain, recognizing that his evaporation model could be “severely unrealistic,” 3 began investigating a hydrodynamic approach that incorporated thermodynamic principles that Parker had ignored. He maintained that measurements taken by spacecraft would show outward flowing plasma speeds of about 18 km/s.

Launched in 1959, the Soviet Union’s Luna 1 and Luna 2 probes put Parker’s and Chamberlain’s proposals to the test. As a team led by Russian physicist Konstantin Gringauz reported in a fall 1960 paper, the Luna particle detectors measured positively charged particles with energies exceeding 15 keV, which implied that proton speeds exceeded 50 km/s. 4 Unfortunately, the spacecraft were not equipped to determine the direction of particle flow. The debate was finally settled in Parker’s favor two years later, when an instrument on the US Mariner 2 spacecraft, operated by Marcia Neugebauer and Conway Snyder of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, determined that the plasma was coming directly from the Sun at a velocity of about 400–700 km/s. 5 The solar wind is now an integral part of our understanding of the solar system.

Open or closed magnetosphere?

Space physicists soon realized that Earth’s magnetic field would form an obstacle for the solar wind. But the extent to which it would do so was unclear. The big question was whether the space in which the motion of charged particles is determined by the terrestrial magnetic field—what is now termed the magnetosphere—is open or closed to the entry of solar wind particles. In the open model, magnetic field lines embedded in the solar wind merge with Earth’s magnetic field, allowing the particles to enter the magnetosphere. That is not the case for the closed model.

The roots of that debate lay in the immediate postwar period, when physicist Ronald Giovanelli of the National Standards Laboratory in Sydney, Australia, noticed that solar flares seemed to be associated with the oppositely directed magnetic fields that are found near sunspots. In 1946, he speculated that those field lines might merge, energize plasma, and cause flares. 6 One of the external examiners for Giovanelli’s PhD thesis was Fred Hoyle at the University of Cambridge. Hoyle soon suggested to another student, James Dungey, that he examine how magnetic field lines merge to determine if that process might explain the precipitation of charged particles into Earth’s atmosphere and produce auroras. By 1953, Dungey had articulated a theory of what is now called magnetic reconnection, in which sheets of oppositely directed magnetic field lines merge, causing electrical discharges and the release of charged particles. 7

The US Pioneer 5 spacecraft, launched 11 March 1960, carried a magnetometer positioned so that it could measure the solar wind magnetic field perpendicular to the spin axis of the spacecraft, which was in the ecliptic plane. It found that the magnetic field often pointed out of the ecliptic plane, which in part led Dungey to develop an open model of Earth’s magnetic field. 8

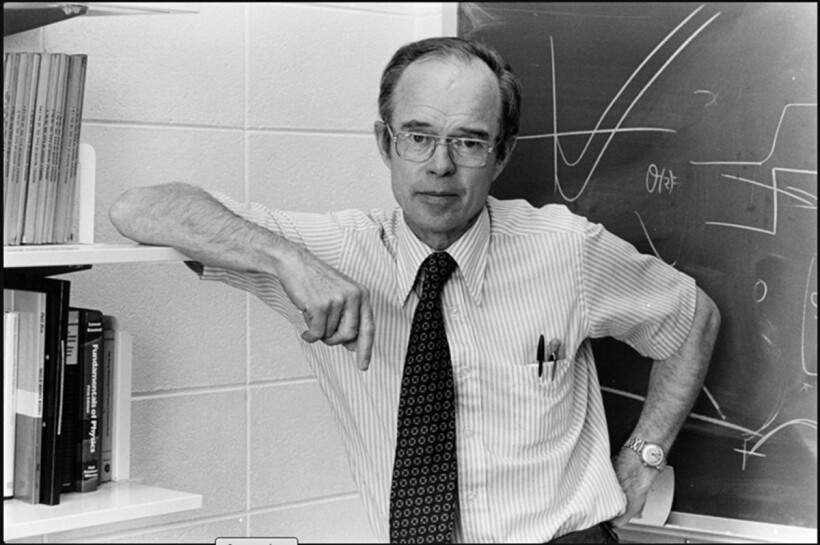

But a colleague of Dungey’s, space physicist Alexander Dessler of Rice University, saw the same data as evidence that Earth’s magnetosphere was closed (see figure

Figure 2.

Schematic renderings of the open (left) and closed (right) models of Earth’s magnetosphere developed, respectively, by James Dungey and Alexander Dessler. (Images courtesy of GreenPepper Media.)

The debate continued for several decades. Spacecraft instruments gradually improved and became able to detect magnetic merging at small distance scales. Finally, in 2015, NASA launched the Magnetospheric Multiscale mission: four satellites that fly in formation in an orbit that encounters the nose of Earth’s magnetosphere. Led by James Burch of Rice University, the mission took measurements definitively establishing that the magnetic reconnection process occurred on the electron scale, thereby demonstrating that the magnetosphere is open to solar particles. 10 Both field-line merging and the open magnetosphere model are now essential components of our understanding of the behavior of astrophysical plasma.

Lunar dust

In the 1960s, as NASA was planning to land humans on the Moon, space scientists were also turning their attention to Earth’s natural satellite. The first crewed landings were to be on the large lunar basins, which many had long assumed were formed by ancient lava flows. But in 1955, Thomas Gold of Cornell University had proposed that the large basins were instead filled with fine dust that resulted from millions of years of bombardment by meteoroids. 11 Suggesting that the dust was “fluidized” either by hot gas generated during meteoroid impacts or by electric forces associated with the photoemission of electrons from the lunar surface, Gold warned in 1958 that the “top few feet [of the lunar surface] may well be extremely loose and more treacherous than quicksand.” 12 His provocative claim set off a heated scientific debate among Gold and several distinguished scientists, including Harold Urey, Fred Whipple, Gerard Kuiper, and Eugene Shoemaker.

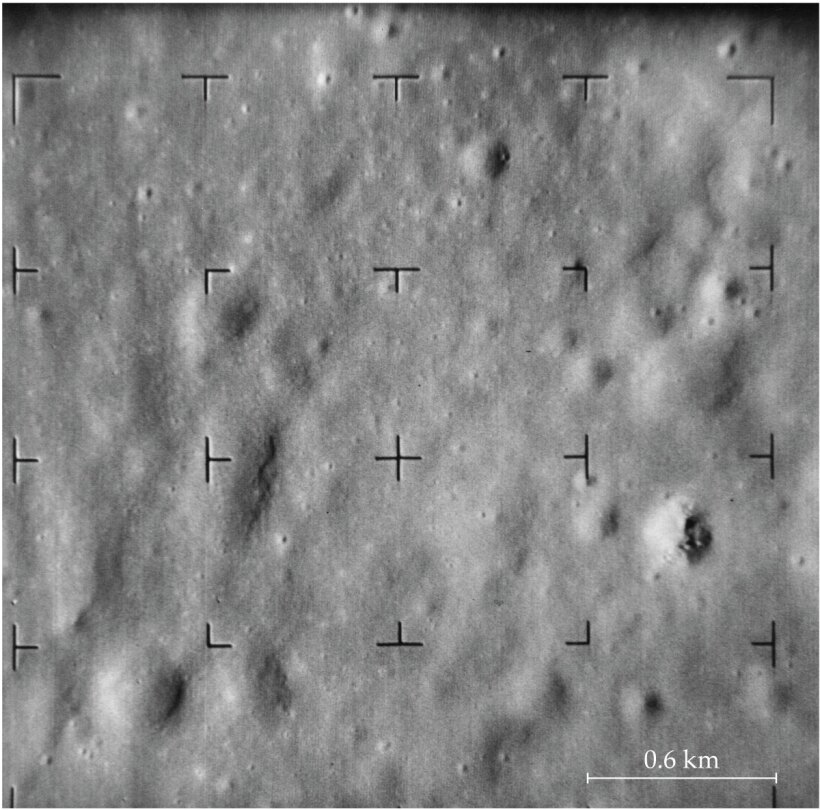

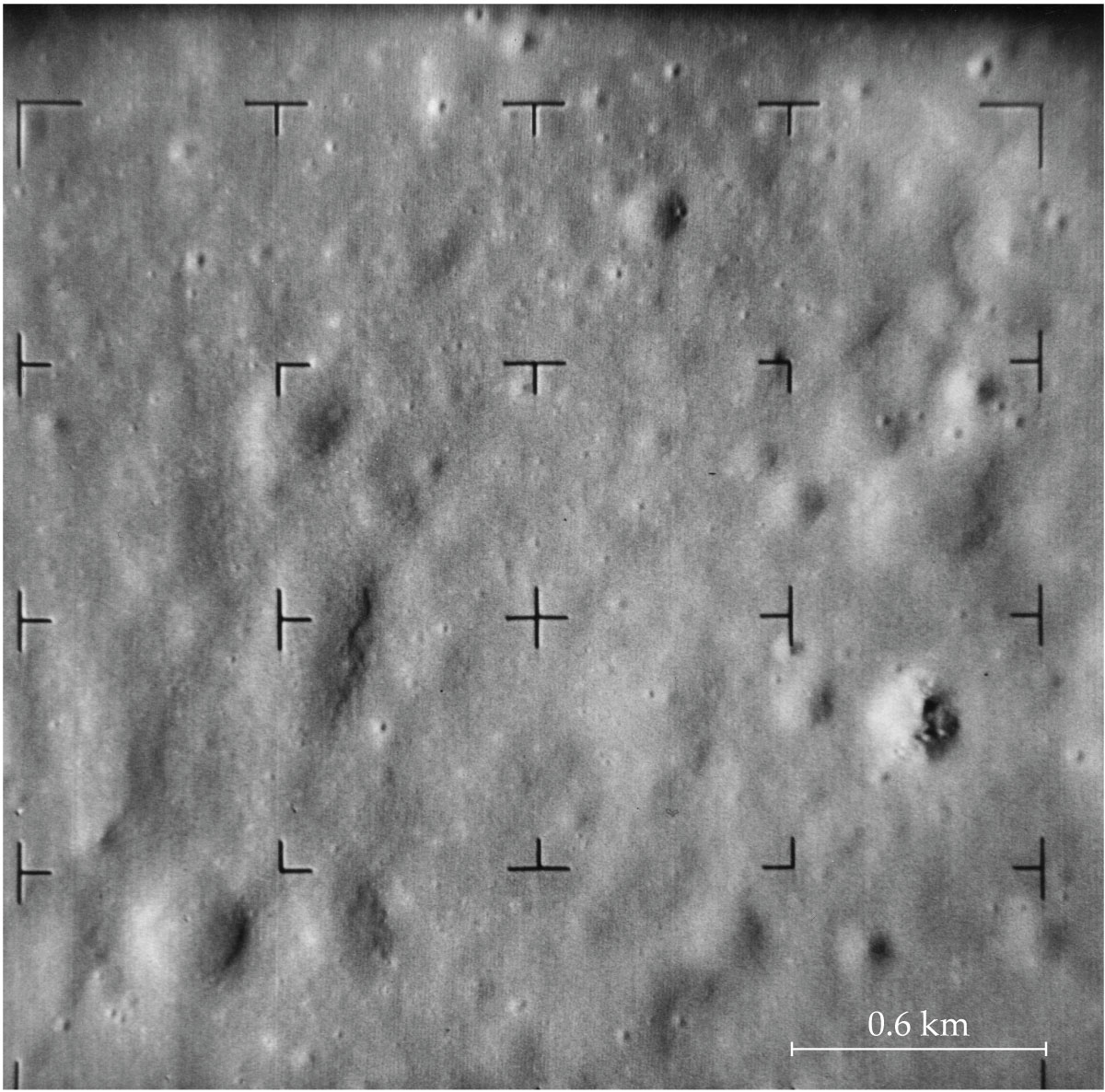

To reconnoiter the lunar surface prior to the first Apollo landing, NASA sent a series of spacecraft that took photos as they approached and ultimately collided with the Moon. The first images, which were returned in 1964, showed small craters with rounded edges that Urey termed “dimple craters” (see figure

Figure 3.

An image of the lunar surface, taken by the Ranger 7 spacecraft in July 1964. (Image from NASA/Lunar and Planetary Institute.)

Subsequent landings by the Soviet Luna 9 and the US Surveyor program allayed NASA’s fears about the success of Apollo exploration of the Moon: The two spacecraft did not sink significantly into the lunar surface. In the end, although the Apollo astronauts had no trouble traversing the lunar surface, they did report the ubiquitous presence of dust that infiltrated equipment and space suits. Dust was blowing so strongly during the Apollo 12 landing that pilot Pete Conrad could not see the surface and had to rely entirely on instruments for the landing.

Gold received a lot of criticism from lunar scientists during the debate about the Moon’s surface. But, as Urey pointed out, “Like all proposals of this kind that any of us make, they are likely to be only partly right, and we ought to be immensely pleased if they are only partly right. I think Gold has made a great contribution in calling our attention to the possibility of dust on the surface of the moon.” 14 Indeed, future crewed missions to the Moon will also need to contend with the hazard of blowing dust during landing.

Sizing up the heliosphere

The Biermann comet-tail paper that sparked Parker’s initial interest in the solar wind also prompted the question as to the size of the cavity the plasma carved out of the surrounding interstellar medium. The first prediction of the size of what we now term the heliosphere in fact pre-dated Parker’s work. Made in 1955 by Caltech physicist Leverett Davis Jr, it estimated the distance to the heliosphere’s boundary—now called the heliopause—to be 2000 astronomical units (AU). 15 Davis’s calculation was based on a rough estimate of the restraining pressure from the interstellar magnetic field.

At a 1960 symposium in Varenna, Italy, Francis Clauser of Johns Hopkins University pointed out that a standing shock wave would slow the solar wind to subsonic speeds—namely, speeds slower than those of hydromagnetic waves in magnetized plasma—at a distance from the Sun short of its boundary with the interstellar medium. Parker, who was also in attendance, then gave a rough estimate of 160 AU as the distance to the standing shock wave, now termed the termination shock. Figure

Figure 4.

A simulation of the Sun’s termination shock in a household sink.

In more than four decades of speculation and cordial-but-spirited debate, estimates of the distance to the termination shock varied widely, from 2 AU to 100 AU. Theoretical and experimental information that formed the basis of the debates included such topics as the measured gradients of galactic cosmic rays in the inner solar system, the entry of interstellar neutral hydrogen into the solar system, the friction of cosmic rays with the solar wind, and planetary and heliospheric radio emissions.

Astronomers hoped that the instruments onboard Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which both launched in 1977, would be able to detect the termination shock and the heliopause. By 1989, with Voyager 1 about 36 AU from the Sun, the termination shock had not yet been detected. That year, attendees at a space science conference at the University of New Hampshire were polled as to when they thought the probe would encounter it. The average response was 61 AU. Voyager 1 would only cross the termination shock in 2004, when it was approximately 94 AU from the Sun. Voyager 2 crossed the termination shock in 2007 at about 84 AU.

Although the debate on the distance to the termination shock was thus resolved, it prompted another significant debate as to the shape of the heliosphere. At least three contemporary models exist: one that is comet shaped, one that looks more like a croissant, and another that takes the form of a beach ball. 16 Space scientists express hope that NASA’s Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, set to launch as soon as this year, will settle the debate.

Sources of gamma-ray bursts

Following the adoption of the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which banned nuclear weapons tests anywhere except underground, the US launched a set of orbiters designed to monitor the Soviet Union’s compliance with the agreement. Known as the Vela satellites, they soon began detecting short-lived bursts of gamma rays, which researchers quickly realized did not come from nuclear explosions. So where did the gamma rays come from? Nearby sources were quickly ruled out: In 1973, Ray Klebesadel, Ian Strong, and Roy Olson demonstrated that the measured gamma rays with bursts as short as 0.1 seconds and as long as 30 seconds could not come from Earth or the Sun.

Further investigations were made by Gerald Fishman and his colleagues at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, who took high-altitude balloon flight measurements in 1975 and 1977 and found no gamma-ray bursts. That led them to state that the sources of the bursts were unlikely to be at extragalactic distances and that they must be in the neighborhood of the Milky Way galaxy.

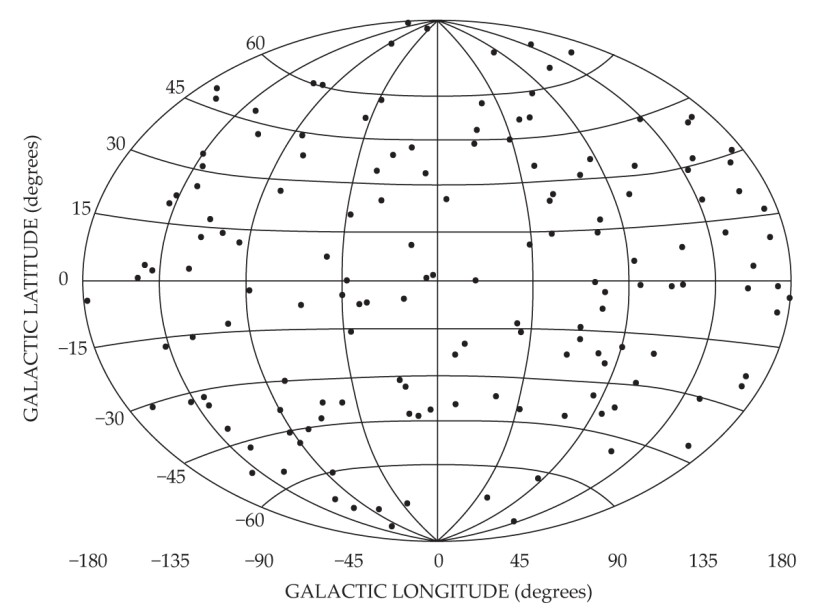

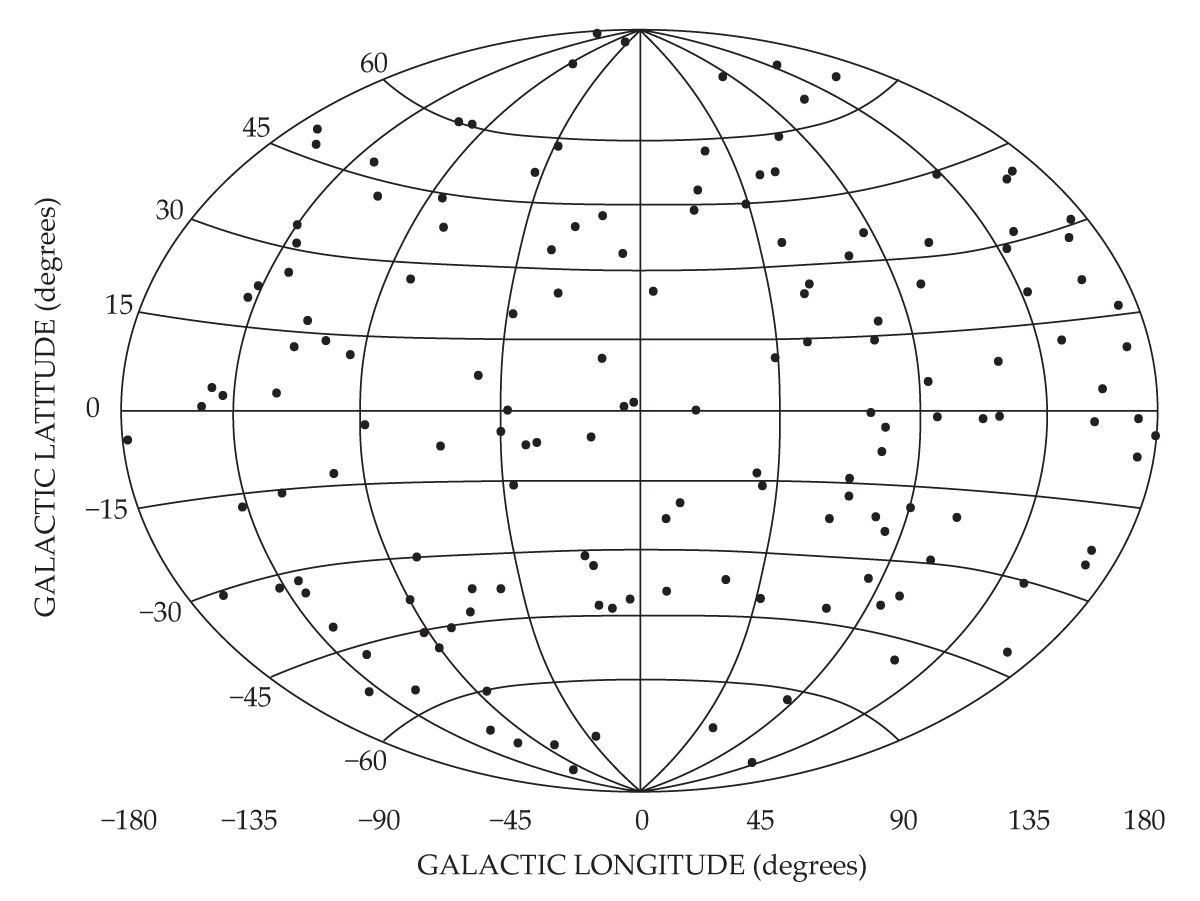

But unlikely is not the same as surely. So Fishman and his team proposed the Burst and Transient Source Experiment (BATSE), an instrument carried by the Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory, which was launched in 1991. Activated in April of that year, BATSE began to record gamma-ray bursts at a rate of about one per day. By 1992, it had demonstrated that the distribution of the bursts is isotropic across the celestial sphere (see figure

Figure 5.

A plot of the 153 gamma-ray bursts detected by the Burst and Transient Source Experiment, an instrument on the Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory, as of January 1992. The angular distribution of the bursts is isotropic across the entire cosmos. Subsequent observations have confirmed that isotropy. (Image adapted from C. A. Meegan et al., Nature 355, 143, 1992

Some researchers at the time argued, however, that the gamma rays might come from a halo of neutron stars around the Milky Way. They suggested that some supernovae could impart high-velocity kicks sufficient to propel neutron stars out of the galaxy. Over time, those ejected neutron stars might form a nearly isotropic halo around the galaxy, which could theoretically produce the distribution of bursts measured by BATSE.

On 22 April 1995, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History hosted a debate between the two sides (see figure

Figure 6.

Buttons worn by attendees at the 22 April 1995 debate between Bohdan Paczyński and Donald Lamb about the origins of gamma-ray bursts. Those who believed that the bursts come from beyond our galaxy wore the red buttons; those who believed that they occur in our galaxy wore the blue ones. (Photo by Pflatau/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

The 1995 debate did not resolve the dispute. A combination of space- and ground-based observations two years later did. In 1997, Jan van Paradijs, of the University of Amsterdam, and his students were able to associate a gamma-ray burst with a specific galaxy. Unfortunately, they were unable to measure the spectra of the emission lines in the host galaxy. Only a few months later, however, a group led by Mark Metzger of Caltech found an optical flash and a gamma-ray burst occurring simultaneously in the same galaxy. The flash contained emissions from elements within the galaxy, and the spectra of those emissions could be measured. The Doppler shift of the emission lines in the gas of the host galaxy established beyond doubt that the burst sources were outside our galaxy. 18 We now know that gamma-ray bursts are the most powerful phenomena in the universe. Studying them has helped astronomers further refine our understanding of the cosmos.

This article was originally published online on 13 January 2025.

References

1. E. N. Parker, Astrophys. J. 128, 664 (1958). https://doi.org/10.1086/146579

2. J. W. Chamberlain, Astrophys. J. 131, 47 (1960). https://doi.org/10.1086/146805

3. J. W. Chamberlain, Astrophys. J. 133, 675 (1961). https://doi.org/10.1086/147070

4. K. I. Gringauz et al., Sov. Phys. Dokl. 5, 361 (1960).

5. M. Neugebauer, C. W. Snyder, Science 138, 1095 (1962). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.138.3545.1095.b

6. R. G. Giovanelli, Nature 158, 81 (1946). https://doi.org/10.1038/158081a0

7. J. W. Dungey, Lond., Edinb., Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 44, 725 (1953). https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440708521050

8. J. W. Dungey, Cosmic Electrodynamics, Cambridge U. Press (1958).

9. J. W. Dungey, J. Geophys. Res. 99, 19189 (1994), p. 19190. https://doi.org/10.1029/94JA00105

10. J. L. Burch et al., Science 352, aaf2939 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf2939

11. T. Gold, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 115, 585 (1955). https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/115.6.585

12. T. Gold, in Vistas in Astronautics, Volume II: Second Annual Astronautics Symposium, M. Alperin, H. F. Gregory, eds., Pergamon Press (1959), p. 265.

13. T. Gold, Science 145, 1046 (1964), p. 1048. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.145.3636.1046

14. H. C. Urey, in The Nature of the Lunar Surface: Proceedings of the 1965 IAU–NASA Symposium, W. N. Hess, D. H. Menzel, J. A. O’Keefe, eds., Johns Hopkins Press (1966), p. 20.

15. L. Davis Jr, Phys. Rev. 100, 1440 (1955). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.100.1440

16. M. Opher et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 800, L28 (2015); https://doi.org/10.1088/2041-8205/800/2/L28

K. Dialynas et al., Nat. Astron. 1, 0115 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-017-011517. B. Paczyński, Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 107, 1167 (1995); https://doi.org/10.1086/133674

D. Q. Lamb, Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 107, 1152 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1086/13367318. J. van Paradijs, C. Kouveliotou, R. A. M. J. Wijers, Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 38, 379 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.astro.38.1.379

More about the authors

For more than 30 years, David Cummings was the executive director of the Universities Space Research Association in Washington, DC. Louis Lanzerotti is a Distinguished Research Professor of Physics at the Center for Solar–Terrestrial Research at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in Newark. This article is based on their book, Scientific Debates in Space Science: Discoveries in the Early Space Era, published by Springer in 2023.