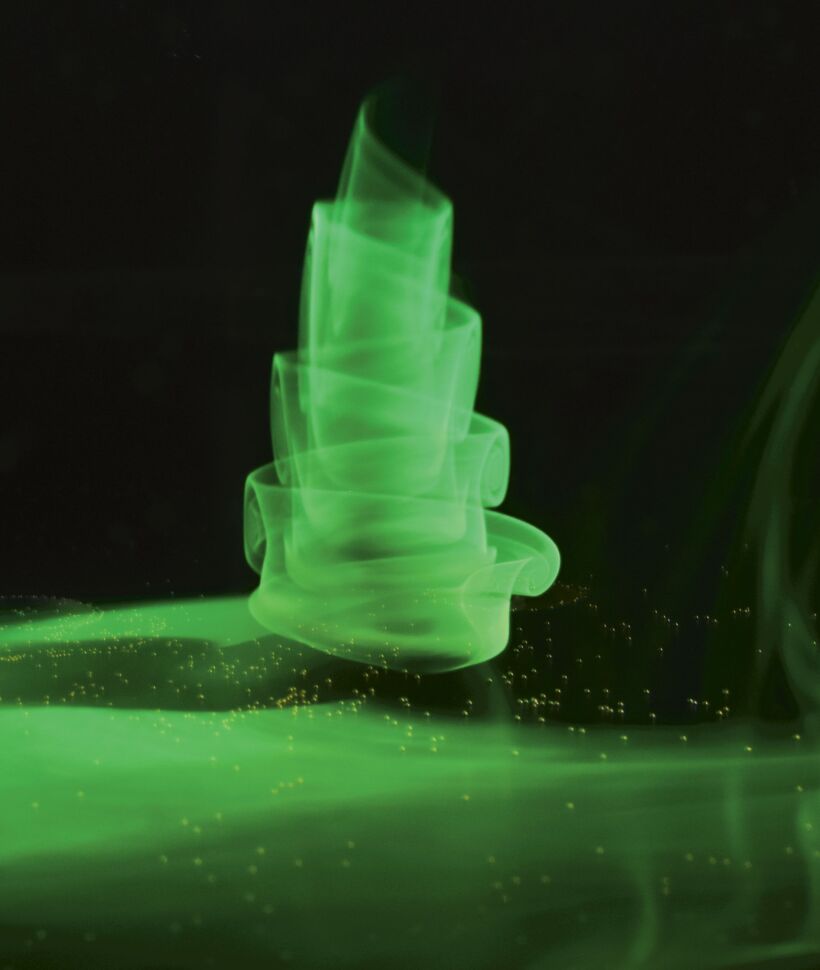

A wandering vortex

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4989

Vortices are found across a wide range of spatial scales and environments, including the water spiraling down a bathtub drain and the whirlpools of cooling plasma that sink into the Sun’s interior. To create a vortex in the lab, a tank of water is typically mounted on a rotating table. The water drain is aligned with the rotation axis, and a vortex appears and remains above the drain. Natural vortices, however, typically follow a more complicated motion.

To model that more realistic situation, Rick Munro (University of Nottingham, UK) and Mike Foster (the Ohio State University) set up a closed cylindrical tank with the drain located at its midradius, filled it with water, and rotated it at an angular velocity of 0.6 rad/s. A vortex initially forms over the drain but quickly moves off by self-induction and follows a more-or-less circular path around the axis until it finally comes to rest. From the tank’s outer rim, fluorescently dyed water spirals inward via the bottom boundary layer before moving upward as it swirls around the vortex core. That motion is seen in this photo, which was taken after 4.2 rotations of the tank. At that time, the vortex has moved a few millimeters off the drain and the dyed water has reached a height of 5 cm. After 25 rotations, it broadens and comes to rest as a hollow-core vortex. (Image courtesy of Cambridge University Press; R. J. Munro, M. R. Foster, J. Fluid Mech. 933, R2, 2022, doi:10.1017/jfm.2021.1098

More about the authors

Alex Lopatka, alopatka@aip.org