A molecular road movie

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4801

The development of instantaneous photography in the 19th century brought new understanding of human and animal movements that were too rapid to observe with the naked eye. Suddenly, it was possible to see with certainty that all four hooves of a galloping horse left the ground at once. Similarly, a central theme of modern physical chemistry is the observation of chemical reactions at the molecular level and in real time. So-called molecular movies allow researchers to view the intermediate steps of a reaction, not just its results (see Physics Today, August 2003, page 19

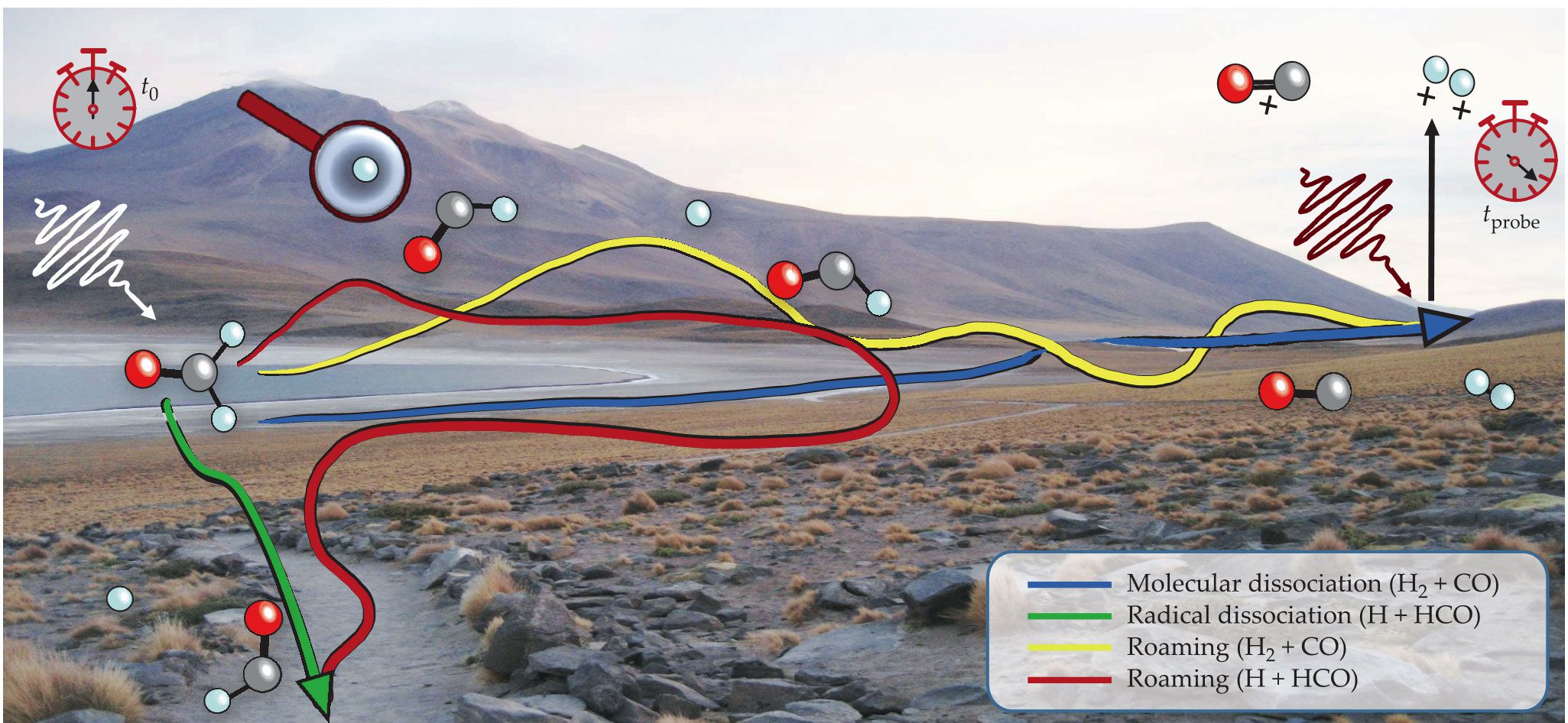

In the conventional view of chemical reactions, atoms follow straight, predictable paths, and one knows exactly where to find them. In a photodissociation reaction, in which a molecule breaks apart upon excitation with light, that simple picture gives rise to two basic types of reaction pathway: Either a single bond stretches until its breaks, or the atoms efficiently rearrange to form a new chemical bond while breaking two others. For the dissociation of formaldehyde (H2CO), those pathways are represented by the green and blue arrows, respectively, in figure

Figure 1.

Many roads on a molecular landscape. When formaldehyde (H2CO) is excited with a UV pulse (white, t0), it can dissociate into either H + HCO or H2 + CO. Conventionally, those reactions were thought to follow straight paths, as represented by the green and blue arrows, but it’s now known that they can follow more tortuous roaming trajectories. To catch the roamers on the road, we ionize the dissociating molecules with a probe pulse (brown, tprobe) and reconstruct their geometry from the ensuing Coulomb explosion. We found that roaming trajectories can lead not only to molecular products (yellow line) but also to radical products (red line). (Image by Heide Ibrahim, adapted from A molecular road movie, https://youtu.be/CQ3Cril0YSA

Sometimes, however, atoms slip loose and wander off into the wild. Their destinations are unknown, and their trajectories can be all over the map. Tracking their unpredictable paths is not easy, even when using the best time-resolved spectroscopic methods. We need to turn to powerful techniques sensitive to single molecules.

Roaming atoms

The elusive phenomenon now termed “roaming” surprised researchers when they discovered it in the dissociation of H2CO in 2004. It is illustrated in figure

Roaming is now known to occur in many molecular systems. It’s generally observed indirectly, through the spectroscopic imprint it leaves on the reaction products. When H2CO dissociates into H2 and CO, roaming reveals itself through the distributions of H2 vibrational states and CO rotational states. However, such indirect detection provides little information about the exact molecular pathway and the dynamics of the moving fragments. Even time-resolved experiments have, until now, been limited to the indirect observation of the outcome of processes that involve roaming. To observe roaming in real time, we must expand the concept of the molecular movie into a molecular-road movie: to identify not just the individual moving fragments but also the different roads they travel.

Directly observing roaming in dissociating H2CO is challenging because of the unpredictability of the process. Each roaming fragment follows its own path, no two of which are alike. Furthermore, although the roaming process itself lasts just a picosecond or less, it could take up to tens of nanoseconds to get started, so at any given instant, only a tiny fraction of molecules might be caught in the act of roaming. Finally, many of the molecules still follow the conventional, direct dissociation pathways, which cross the roaming pathways and can therefore be difficult to distinguish. We needed a way to extract the roaming dynamics hidden behind the overwhelming statistical background.

Explosive imaging

We chose Coulomb-explosion imaging, an established technique in which a short, intense laser pulse ejects several of a molecule’s electrons at the same time. The ionic fragments repel one another and fly apart, and from their trajectories toward a detector, we can reconstruct the molecular geometry at the time of ionization. Not only is the technique sensitive to single molecules, but we can also isolate specific channels from the background by using ion correlations and thus select statistical events. At the Advanced Laser Light Source, headed by François Légaré, we have filmed the roaming dynamics of deuterated formaldehyde (D2CO), which we chose over H2CO for experimental reasons.

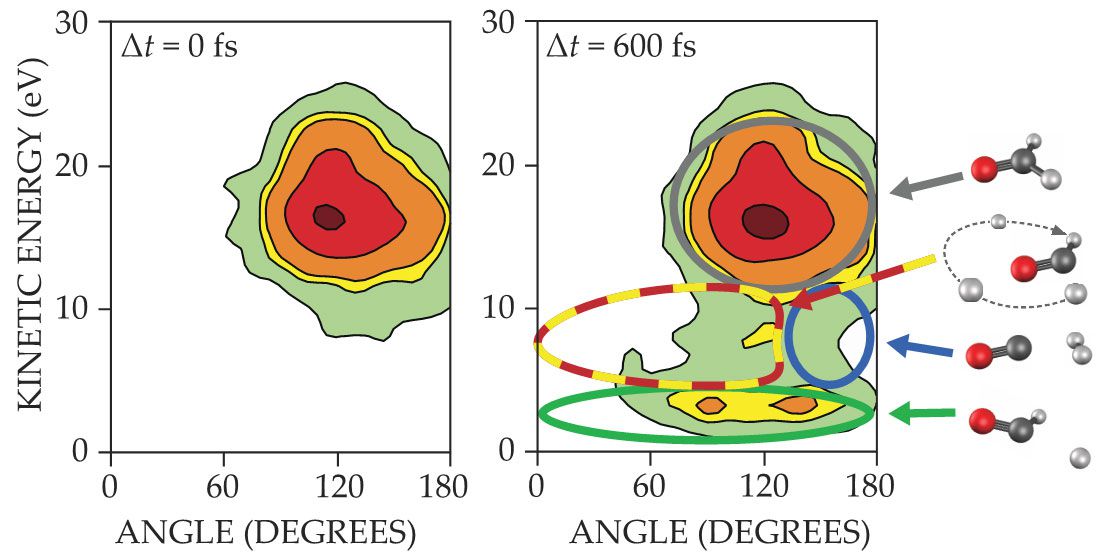

We can capture a snapshot of an ensemble of dissociating molecules at any desired moment with femtosecond precision by adjusting the time delay between the photoexcitation pulse and the ionization pulse and then correlating the signals from the D+, D+, and CO+ ion fragments. Supported by the theory groups of Michael Schuurman, Paul Houston, and Joel Bowman, we distinguished the possible pathways by plotting the kinetic energy released in the Coulomb explosion against the angle between the two deuterons’ momentum vectors as they fly apart. We cannot sharply separate all the regions, because deuterons undergoing conventional dissociation must pass through the same configurations as roaming ones. But for the most part, we can classify the pathways according to the outlines in figure

Figure 2.

Snapshots of dissociating D2CO molecules, with the total kinetic energy released in the Coulomb explosion plotted against the angle between the two deuteron momentum vectors. Geometries that correspond to different molecular roads are marked by the colored curves: gray, equilibrium; red–yellow dash, roaming; blue, molecular dissociation; green, radical dissociation. (Figure by Tomoyuki Endo and Heide Ibrahim.)

The gray circle marks the region of undissociated D2CO molecules. Before ionization, their atoms are bound together, so in the Coulomb explosion, the charged fragments strongly repel one another for a large kinetic energy release.

The blue circle indicates molecules following the conventional dissociation pathway to D2 + CO: The two deuterons are near one another but far from the CO fragment, so they fly apart in nearly opposite directions. The green ellipse represents the conventional pathway to D + DCO: The departing D atom is already almost gone, so its repulsion in the Coulomb explosion is small, and its momentum direction is almost uncorrelated with the other D atom’s.

The red and yellow dashed curve shows molecules in the act of roaming, with one deuteron roaming around the remaining DCO fragment. That configuration leads to a larger kinetic-energy release than the conventional D + DCO pathway but a smaller D–D angle than the D2 + CO pathway.

With this work, we generalized the definition of roaming to include processes recognized by their transient features, not just their outcomes. Because we catch the roamers on the road, we can detect them whether they complete the roaming path or end up in a conventional dissociation channel. Previous measurements of roaming in H2CO relied on the quantum states of CO and H2, so they were sensitive only to roaming pathways that yield those products, like the yellow trajectory in figure

References

► D. Townsend et al., Science 306, 1158 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1104386

► J. M. Bowman, B. C. Shepler, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 62, 531 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103518

► A. G. Suits, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 71, 77 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physchem-050317-020929

► M. S. Quinn et al., Science 369, 1592 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc4088

► T. Endo et al., Science 370, 1072 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc2960

► P. L. Houston, R. Conte, J. M. Bowman, J. Phys. Chem. A 120, 5103 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.6b00488

More about the authors

Tomoyuki Endo is at the National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology in Kyoto, Japan. Chen Qu is at the University of Maryland, College Park. Heide Ibrahim is at INRS in Varennes, Quebec, Canada.