Why Pluto looks so patchy

Even before the New Horizons space probe sent back the first close-up images of Pluto, astronomers knew that the solar system’s largest trans-Neptunian object (TNO) has a surface whose albedo varies dramatically from place to place. In principle, Pluto’s obliquity (a body’s axial tilt with respect to its orbital plane) and its substantial orbital eccentricity (0.24) could be responsible for the patchy appearance. At 119°, the high obliquity yields huge seasonal variations in insolation that alter Pluto’s frigid surface through the periodic deposition and sublimation of ice.

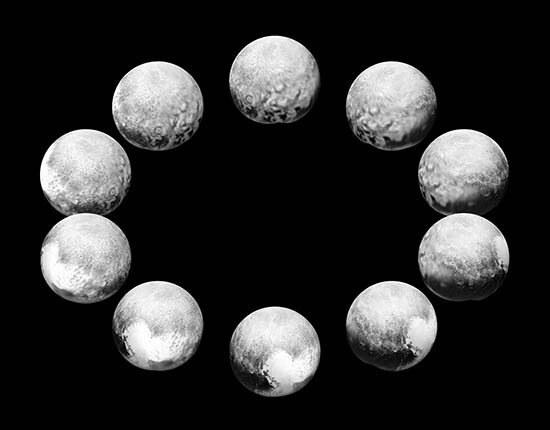

NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

On 14 July 2015, when New Horizons made its closest approach, spring was coming to Pluto’s northern hemisphere and the TNO was about one-quarter of the way around its 248-year orbit from perihelion to aphelion. As the accompanying figure shows, Pluto’s north pole (the white area in the bottom images) is indeed icy. But if obliquity and eccentricity were the only influences in play, why does Pluto’s albedo vary not just with latitude but also with longitude?

To answer that question, Alissa Earle of MIT and her collaborators modeled how Pluto’s majority surface constituent, nitrogen, responds to variable insolation. Effects due to Pluto’s 6.4-day diurnal rotation were averaged out, but the model incorporated the long-term periodic variation in obliquity (±23° in less than 3 million years) and the precession of the orbit’s major axis (360° in 3.7 million years). The model divided Pluto into three 120°-wide longitudinal zones and covered them with ice of three albedos: 0.1, 0.3, and 0.6. And if all the ice at a location sublimated away, a subsurface of albedo 0.1 would be exposed.

In general, the model found that the amount of ice deposited at the polar regions depended little on albedo: When a pole faced the Sun, it would have thin ice; when it was in shadow, it had thick ice. A more interesting effect occurred in equatorial and midlatitude regions. Pluto’s high obliquity created the possibility for what Earle and her colleagues call runaway albedo. Once an area attains a low albedo, it tends to keep it because the surface stays warm enough to forestall the deposition of ice, which would raise the albedo. Similarly, once an area attains a high albedo, it tends to keep it because the surface stays cold enough to forestall sublimation, which would lower the albedo. In the model, the albedo variation with longitude was put in by hand. On Pluto, the variation arises naturally when dark organic molecules precipitate from the atmosphere. The study suggests that, once established, dark and light patches on Pluto’s surface can persist for millions of years. (A. M. Earle et al., Icarus 303, 1, 2018