Watching how DNA gets fixed at the atomic level

In this beam tunnel of the SwissFEL facility at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland, x rays are generated to probe the extremely fast processes of proteins and various chemical reactions, including how DNA gets repaired by a photoenzyme.

Paul Scherrer Institute/Markus Fischer

Against the harmful effects of sunlight on DNA, nature has developed some defenses. Incoming UV photons have enough energy to trigger consecutive DNA base pairs to distort the well-known double-helix geometry and form what are called cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs), which disrupt DNA replication and cause skin cancer. In response, some organisms—though not humans—have enzymes called photolyases. Powered by visible light, they repair the damage through a series of reactions on the CPDs.

Thanks to spectroscopy findings and theoretical studies, scientists have known about the DNA repair process for the past 30 years. But the exact mechanism and the structure of the chemical species at play have been difficult to visualize. Among the challenges is that the damaged DNA and the photolyase must be acquired in dark, oxygen-free conditions. And the repair process operates at atomic resolution over time scales of picoseconds to microseconds.

Now the repair has been caught in action. Two separate teams—Manuel Maestre-Reyna of Academia Sinica and National Taiwan University in Taipei and colleagues and Nina-Eleni Christou at the German Electron Synchrotron in Hamburg and colleagues—used a technique known as time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography to obtain snapshots of the process and make a timeline of its key events.

The results come from data collected at three of the world’s five hard x-ray free-electron lasers. Tiny crystals of a photoenzyme found in a species of archaea and its damaged DNA were repeatedly pulsed with high-intensity x rays. Each pulse lasted a few femtoseconds, so short that the x rays diffracted in many directions from the various crystalline faces of the samples before getting destroyed by radiation damage. By combining tens of thousands of diffraction patterns, the researchers created detailed atomic structures of the various intermediate complexes and then assembled them into time-resolved pictures of the DNA’s repair.

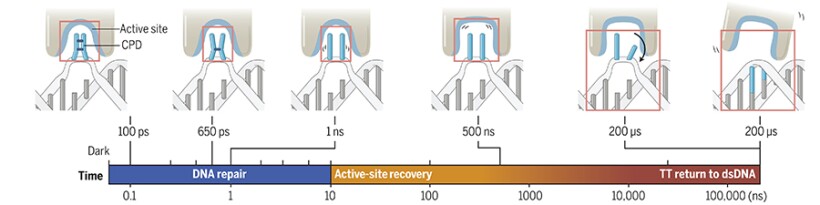

This series of images shows the steps that a photoenzyme takes to repair DNA damaged by the UV-induced formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs).

Adapted from M. Maestre-Reyna et al., Science 382, 1014 and eadd7795 (2023)

The timeline shows a few of the critical steps of the repair process. About 650 ps after the photons’ arrival, the photolyase (tooth-shaped structure) breaks one of the carbon–carbon bonds (dark blue bars) of the CPDs followed by another shortly thereafter, which opens the cyclobutane ring. The newly straightened thymine base pair is then able to rotate and reattach to the double-strand DNA. (M. Maestre-Reyna et al., Science 382, 1014 and eadd7795, 2023

More about the authors

Alex Lopatka, alopatka@aip.org