US nano thrust tilts toward technology transfer

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2111

The trend of researchers packaging their ideas to fit into a category that includes the hyped prefix “nano” has slowed, as has the scaremongering of what the field might wreak, epitomized by the nanobots in Michael Crichton’s 2002 novel Prey. But nanoscience and nanotechnology are here to stay.

Since January 2000, when President Bill Clinton rolled out plans for the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI), huge advances have been made in developing, characterizing, and using nanomaterials. The NNI coordinates nanoscale R&D across the government, academic, and private sectors, but does not have its own budget. Rather, NNI investment is tallied across the 27 participating agency and departmental units, with NSF, the National Institutes of Health, the federal Energy and Defense Departments, and NIST spending the most. So far, including the fiscal year 2014 request, the federal government has put almost $20 billion into the NNI, and its current annual investment stands at about $1.7 billion.

Within a couple of years of the NNI’s launch, similar programs were started in 60 countries, says Mihail Roco, senior adviser for nanotechnology at NSF. “Nano is the most exploratory field as a general foundation. It penetrates everything,” he says. Control of matter at the nanoscale, defined for NNI purposes as 1–100 nm, has crosscutting implications from healthcare to climate change.

It’s hard to tease out those advances that are directly due to the NNI from those that might have occurred without it. But it’s safe to say that the NNI has done much to call attention to the field, create educational and research infrastructure, encourage cooperation among agencies, and build environmental health and safety awareness into a burgeoning field from early on. Now, says the DOD’s Lewis Sloter, “We are at a point of demonstrable and observable maturation in nanotechnology.” The NNI is shifting focus accordingly. Basic research and the creation of nanoscale components such as carbon nanotubes, graphene sheets, and quantum dots continue, but there is also a strong emphasis on technology transfer.

Broad, open-ended goals

From the outset, policy makers and scientists recognized that it could take two decades or more to achieve the NNI goals. The long-term, government-initiated thrust has led to comparison with the Apollo program of the 1960s and 1970s. The comparison is apt up to a point: Both brought visibility and focus to a field; both spawned many spin-off products and companies; both excited interest in science among the public and students. But the NNI goals are broader and more open-ended.

To date, a couple hundred nanotechnology-related medical therapies have either hit the market or entered clinical trials (see, for instance, the article by Jennifer Grossman and Scott McNeil, Physics Today, August 2012, page 38

Apart from nanotechnology applications, the NNI has made inroads in education, interagency collaborations, and society more broadly. The number of US universities offering courses in the field has skyrocketed. And nearly 100 interdisciplinary centers under the NNI umbrella have been established at universities and national labs in topics from cancer nanomedicine to integrated sensors to molecular spintronics. “The list is pretty astonishing,” says Cyrus Mody, a historian of science at Rice University. Another NNI legacy may be tighter collaborations among government agencies. “Take the EPA,” says Mody. “There is a solid group that is involved in nanoscience. That might not have happened if the NNI hadn’t drawn attention to the areas of mutual interest.” And, notes Sloter, the structure of the NNI is valuable in bringing all the federal agencies together “as a nexus for broad international collaborations in nanotechnology.”

Barbara Harthorn, director of the Center for Nanotechnology in Society at the University of California, Santa Barbara, notes that “the upstream involvement and raising of questions” in the public sphere has “elevated the discussion about responsible development.” Educational and societal research and outreach activities account for only about 2% of total NNI money. But, she says, “It has brought us to the table, and we fly around like crazy trying to articulate the cultural and historical contexts and fully engage people on the importance of weighing benefits and risks.”

“How safe is nanotechnology?” asks André Nel, director of the Center for the Environmental Impact of Nanotechnology at the University of California, Los Angeles. No disease or major environmental impact has occurred due to nanotechnology, he says, “but anytime you introduce a new technology, it’s important that you consider the potential adverse outcomes and seek ways to prevent them.” Nel points out that nanotechnology can be used for the good of the environment, especially for “reducing the footprint” of other technologies. Still, he notes, “we want to make sure that if nanomaterials end up in landfills, water sources, food, and nanomedicines, they do not have harmful effects.” In short, he says, “Work remains to be done” to make sure that nanotechnology is implemented safely and sustainably.

“Skin in the game”

“A big difference I see from the beginning of the NNI to now is the amount of understanding we have for making and controlling nanoparticles,” says University of Michigan computational physicist Sharon Glotzer. “More importantly, there has been a radical change in mindset about the way we do materials design and discovery. We are shifting our focus from self-assembly to assembly engineering, and that’s changing what we are able to do.”

Glotzer predicts that 3D printing “will be as disruptive as the internet.” Imagine a world in which you need a fork, a battery, or any inanimate object, she says, “and you go to something that looks like your microwave, dial in your item, and you get it—designed to your specifications.”

“We need the NNI in order to say the field is important enough that we will put sustained funding in over the long term. So nanotechnology is an area to which you should bring your best ideas and your brightest minds,“ says Glotzer. That is the power of the initiative, she adds. “It says we—the scientific community, industry, the funding agencies, the taxpayers—are all putting skin in the game.”

The field has reached a point “where you can say, Here’s a problem; is nanotechnology part of the solution?” says Sally Tinkle, who recently moved from a stint as deputy director of the National Nanotechnology Coordinating Office to the Science and Technology Policy Institute, which advises the White House and government agencies on S&T issues.

Signature initiatives

Cancer diagnosis and treatment, disaster recovery, potable water, renewable energy, and environmental cleanup are examples of problems for which nanoscience is often offered up as having solutions. Many of the areas in which nanoscience can play a role are big enough to be initiatives on their own. And indeed, some are, like the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership and the Materials Genome Initiative, launched in 2011, and the BRAIN Initiative, announced earlier this year.

Within the NNI the tack now is to create thrusts, known as “signature initiatives,” in areas expected to benefit economic growth, national security, and environmental protection. “If you want to have closer collaboration and coordination, nanotechnology has become too broad a category,” says Thomas Kalil, head of technology and innovation in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. “The signature initiatives are a device for more focused collaborations in areas where we want to make a big push.”

The first three of these initiatives were launched in 2010, and two more got started this past spring. They focus on solar energy, nanomanufacturing, nanoelectronics, computer modeling and data sharing, and sensors. To bolster attention to the topics, the NNI is reorganizing the categories it uses to keep tabs on money spent in nanotechnology by the partner agencies.

“The NNI has taught us to work in interdisciplinary teams,” says Eric Amis, director of physical sciences research at the research center for United Technologies Corp, a global aerospace and building systems company. “It has also created measurement facilities that can be helpful for companies like UTC.”

“Industry can play a more significant role going forward” with bringing nanotechnology to market, Amis says. “We are doing research to make more efficient air conditioners, elevators, and jet engines. The challenge is that to see the applications through, you have to deal with cost, quality, and reliability when you scale up.”

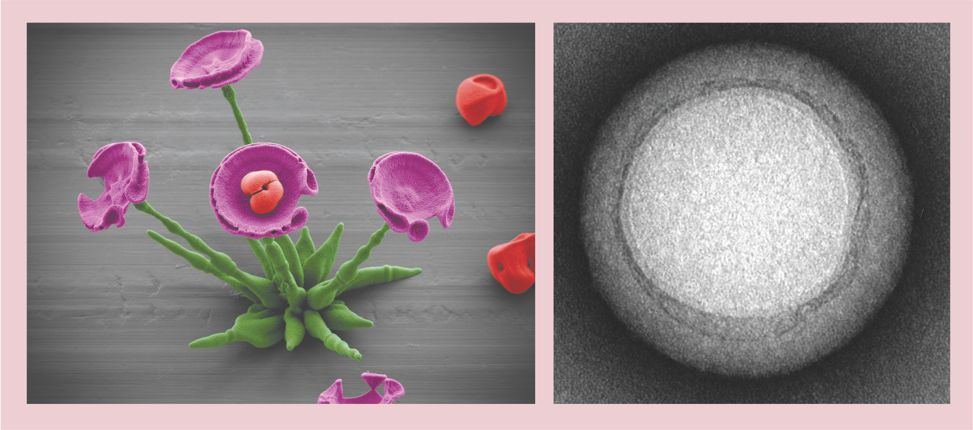

Chemically sculpted flower-like structures (left; in false color) up to 70 µm tall illustrate how micro-architecture is moving to a level of control needed for optical materials, catalysts, and other applications. And these 80-nm-diameter nanosponges (right), with their biodegradable, biocompatible polymeric cores camouflaged in red blood cell membranes, can circulate in the bloodstream to remove toxins such as E. coli and snake venom.

WIM NOORDUIN / ZHANG RESEARCH LAB AT UC SAN DIEGO

A passenger plane as conceptualized by researchers at MIT and NASA would exploit nanomaterials to cut weight, monitor performance to reduce emissions and improve safety, resist ice accretion, and change aerodynamic properties based on atmospheric conditions.

COURTESY NASA, MIT, AND SPRINGER (NANO 2020)

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org