University researchers get back to their experiments

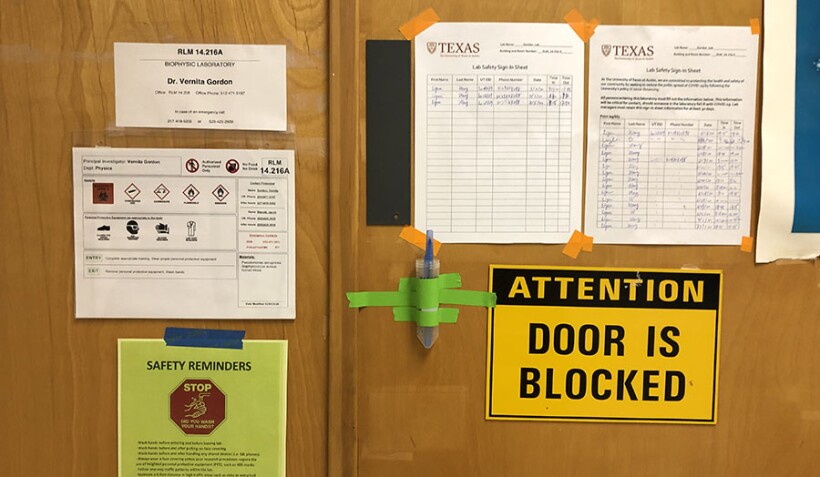

The lab door of biophysicist Vernita Gordon at the University of Texas at Austin reveals that things remain far from normal even as experimental research resumes in labs across the country.

Liyun Wang

Are you wearing a mask? Have you filled out a health screening form? Do you have an assigned time slot? Did you wipe off the doorknob?

Researchers at US universities are restarting their experimental programs after an unprecedented hiatus that began in March when the COVID-19 pandemic prompted lockdowns across the nation. The startup requires health monitoring, limited occupancy and hours, disinfection of surfaces and equipment, and other precautions. The rules vary by state and institution, but before anyone can set foot in a lab, a safety protocol individually tailored for that lab must be approved.

To maintain social distance, universities and departments have imposed occupancy limits. Roughly 30% occupancy is typical—in early July it jumped to 50% in some places—but implementation varies. At the University of Texas at Austin, for example, 30–40% of each research group can go into a lab. Only those people specified by a professor are allowed in the building. Vernita Gordon, a UT biophysicist, chose a postdoc and a senior graduate student in her group, both of whom are close to finishing their projects.

At the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, experimental physics research started up again in early June, with three members of each research group allowed to work in the lab at any given time. To keep within the building limits and optimize work, offices remain off-limits, says physics chair David Gerdes.

At building entrances on the Michigan campus, health officers measure people’s temperatures and ask health-related questions. A cleared person then wears a sticker that says, “I’ve been screened.” Many universities use an honor system that requires people to take their own temperature and certify a lack of symptoms before they can enter campus. At Michigan and most places, entry is via card key, and a record of who has been where is retained so that contact tracing can be implemented if someone contracts the coronavirus.

Dan Stamper-Kurn of the University of California, Berkeley, worked out safety protocols for his lab in consultation with colleagues around the country. The air filters that keep the optics clean, he says, also help clear the lab of any aerosols that may be present. Each researcher in the group now has their own laser goggles, computer keyboard, and mouse, since those are hard to disinfect. Like many other scientists, Stamper-Kurn and his group are working on making equipment remotely operable. The buildings at Berkeley reopened with limited hours, from 8:00am to 8:00pm, largely so custodians can maintain social distancing when they clean.

Dan Ralph is a condensed-matter physicist at Cornell University who works on magnetic devices. During the shutdown, he says, people could enter their labs for maintenance purposes or for COVID-related studies. The gradual reopening prioritized areas of research, starting with health, agriculture and food, national defense, and research in support of other essential businesses. With those categories, most physical sciences could start up to some extent, Ralph says. “In my lab, no more than one person can be in a room at a time.” Most groups arrange shifts in hours, but because of research needs, some groups are blocking out shifts of several days. Many labs also require some time to elapse between successive researchers.

At the University of California, San Diego, Alex Frano is a condensed-matter physicist who studies transitional metal oxides. His group synthesizes samples and characterizes them on site and at national synchrotron light sources. He had beam time canceled because of the pandemic, he says, but so far still has plenty of data to analyze. Some synchrotron user facilities are starting to let people send in samples and oversee measurements remotely.

Graduate students Ruben Rojas (left) and Artur Perevalov celebrate completing a step toward draining 12 tons of metallic sodium from a 3-meter-diameter model of Earth at Dan Lathrop’s University of Maryland lab.

Ruben Rojas

A bottleneck for many physicists is sample preparation. Says physicist James Analytis of the University of California, Berkeley, “The way we make materials is laborious, with assembly, chemical reduction, weighing, and grinding. This work is best done by teams of people, and social distancing makes that tricky.”

“We are all very happy to be somewhat back in the lab,” says University of Maryland physicist Dan Lathrop, whose group is investigating how Earth generates its magnetic field. The three-year project is four months behind due to the lockdown, he says.

Nearly everywhere, research is progressing more slowly than usual, and many groups are supplementing experiments with simulations and theoretical calculations, doing literature reviews, and writing papers and grant proposals. “We are trying to stay as productive as we can given the circumstances,” says Ralph. “Any student who can do their candidacy exam is doing it now.”

The requirement for social distancing makes training new graduate students nearly impossible. “We haven’t figured out how to do this without people being close together,” says Pat Watson, director of user programs at the University of Pennsylvania’s Singh Center for Nanotechnology. What’s more, he notes, his university hasn’t allowed undergraduates back into the labs. The local Research Experience for Undergraduates was among the programs canceled this year, he says. Some universities are mentoring REU students remotely. Some are restricting entrance to visiting scientists.

Under the current constraints, says Analytis, research is by necessity more focused and less spontaneous than usual. “There is less ‘Let’s try this and see what happens,’ ” he says. “It’s a shame. My best discoveries have been serendipitous.”

With the pandemic still raging, uncertainty persists about teaching, funding, prospects for early-career researchers, and more. As a scientist, says UT’s Gordon, the restrictions and stunted progress can be frustrating, but as a human, she thinks it’s worth erring on the side of caution. With COVID-19 cases soaring in Texas, she says, “I’m worried we will go back to a complete shutdown.”

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org