Transuranic elements may be forged in stellar explosions

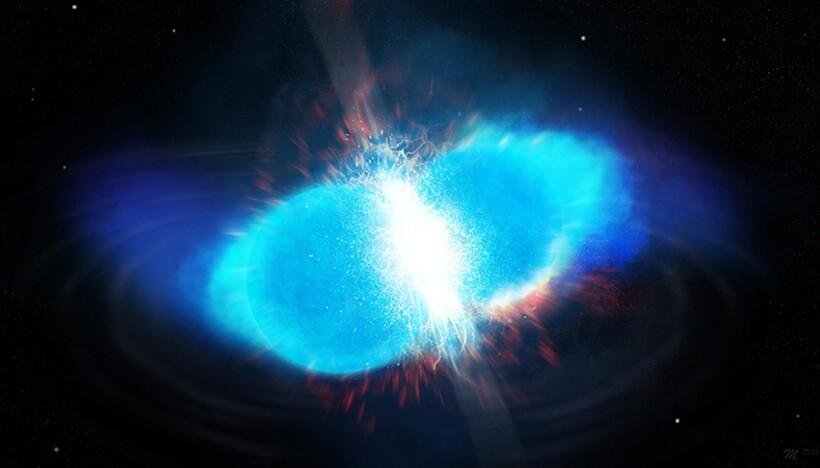

Two neutron stars collide in this illustration. The extreme conditions in the moments following such smashups likely result in the production of nature’s heaviest elements.

Los Alamos National Laboratory (Matthew Mumpower)

According to the periodic table posters hanging in virtually every chemistry classroom, the elements heavier than uranium are almost entirely sourced synthetically. But, as a new study shows, that doesn’t mean nature cannot produce them in bulk. After identifying a puzzling pattern in the stellar abundances of certain elements, North Carolina State University’s Ian Roederer and colleagues have concluded that one of the universe’s essential nucleosynthesis processes forges extremely heavy nuclei—well beyond uranium and its 92 protons—that then undergo nuclear fission to form more common elements.

About half the universe’s supply of elements heavier than iron likely originated during some combination of supernovae and neutron star collisions. In a transformation known as rapid-capture nucleosynthesis, or the r-process, superheated nuclei dispersed during those cataclysmic cosmic events climb the periodic table by ravenously gobbling up neutrons and converting some of them into protons via beta decay (see the article by Anna Frebel and Timothy C. Beers, Physics Today, January 2018, page 30

Rather than waiting on LIGO to offer another live look at rapid capture, Roederer and colleagues examined previously published spectral data to determine the compositions of several dozen Milky Way stars that are particularly enriched in r-process elements. By comparing the stars’ relative concentration of europium, nearly all of which is produced through rapid capture, with that of 31 other heavy elements, the researchers looked for evidence that the r-process is particularly adept at producing specific elements.

Roederer and colleagues found that the abundances of two sets of elements—those with atomic numbers from 44 to 47 and from 63 to 78—rose faster than expected as the stars’ overall r-process enrichment increased. Other elements showed no such correlation. The researchers considered other nucleosynthesis processes and previously identified quirks in the r-process mechanism, but none could explain the relative overabundance of those select elements, which include silver, palladium, and platinum.

The explanation that best fits the data is that some nuclei in those two groups are the daughter species of transuranic nuclei that formed via the r-process and then almost immediately split apart. The researchers’ conclusion is consistent with model predictions that a fissioning superheavy neutron-rich nucleus would yield two nuclei of differing mass. Still, no previous observations had yielded evidence of fission in the cosmos or of the formation of transuranic elements via rapid capture. To explain the stellar measurements, some r-process-produced nuclei would need to contain in excess of 260 protons and neutrons—22 more than inside the most abundant uranium isotope. (I. U. Roederer et al., Science 382, 1177, 2023

More about the authors

Andrew Grant, agrant@aip.org