To redefine kilogram, experiments must weigh in

DOI: 10.1063/1.2207031

The measurement of mass is due for a makeover, pending convergence of two experiments. That consensus was reached last October by the International Committee for Weights and Measures, and the kilogram—along with the ampere, kelvin, and mole—could be redefined in terms of fundamental constants as early as 2011.

“One has to go back to the original definitions of the meter and the kilogram at the time of the French Revolution,” says Terry Quinn, emeritus director of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), located outside Paris. “What they wanted to do was to have some unit that was universal, available to everyone, and not based on the length of the king’s arm.” A century later, in the late 1800s, following the rise in trade and manufacturing, industrial nations formalized definitions for weights and measures, he adds. Since 1889, the international standard kilogram has been a cylinder made of a platinum–iridium alloy and housed at the BIPM.

In the meantime, the second has gone from being a fraction of a day to being linked to the period of a hyperfine transition of cesium. And the meter has progressed through being a fraction of the Paris meridian, the length of a reference bar, and the wavelength of a transition of krypton to the current definition, set in 1983, as the distance light travels in a vacuum in 1/299 792 458 of a second. Indeed, the kilogram is the only unit in the International System of Units (SI) still based on a material artifact. By comparing the international standard to national copies, says Richard Davis, head of the BIPM mass section, “we estimate the mass has changed by about 50 parts per billion [ppb] over 100 years.” Adds Quinn, “We want to have our reference standard better than that—units need to be defined to at least the precision with which measurements can be made. It’s not a matter of whether to redefine—it’s really a matter of what’s the timing.”

Exact constants

A proposal early last year by Quinn and four others to move ahead immediately met with opposition in the mass metrology community. “If the kilogram were redefined prematurely, before experiments attain sufficient uncertainty, I think we would have problems,” says Michael Gläser of Germany’s national standards lab in Braunschweig. In particular, the value of the kilogram might have to be tinkered with.

In an article in Metrologia this spring, Quinn and his coauthors widen their proposed SI overhaul. They favor redefining the kilogram so as to fix the Planck constant h to an exact value, although linking it to the Avogadro constant N A is also an option. They would also redefine the ampere to fix the elementary charge e, the kelvin to fix the Boltzmann constant k, and the mole to fix N A. The new definitions would shunt the uncertainties from fundamental constants to units, and from microscopic to macroscopic quantities. “You can’t get rid of the uncertainties,” says Quinn. “They pop up somewhere else.”

The kilogram can be related to h using a moving-coil watt balance, which weighs electrical power against mechanical power, or to N A by counting a large number of atoms in a crystal using a combination of x-ray and optical interferometry. So far, results from the two methods are off by about one part per million—far more than the suspected drift of the standard kilogram.

The best prospects for resolving the discrepancy lie with the Avogadro experiment: An international team is preparing to measure the lattice spacing, density, and molar mass of a single-crystal sphere of isotopically enriched silicon, rather than using nature’s mix of three isotopes as in previous experiments. If the discrepancy between the two approaches proves real, says NIST’s Barry Taylor, a proposal coauthor, “that would tell us something is peculiar with the physics. But we think it’s measurement problems.”

Redefining the kilogram hinges not only on the results converging, but also on driving the uncertainty down and reproducing the result on more than one of the five watt-balance apparatuses worldwide. “Ours is presently quoting the best uncertainty,” says proposal coauthor Edwin Williams of NIST in Gaithersburg, Maryland, which late last year reported measurements good to 50 ppb. “We have an uncertainty budget that has 15 or 20 components, and we have to work on each of these,” he adds. “We think we can get down to the 20 parts per billion required by the Committee [for Weights and Measures] within the year.”

“The world is not perfect with our kilogram standard, but the problems we have had have not had an impact on science and technology,” says the BIPM’s Davis. “If the watt-balance and Avogadro experiments improve to 10 to 20 parts per billion relative uncertainty, then there is no argument against changing the definition.”

“Intense discussion”

None of the other proposed redefinitions have stirred up debate. The kelvin is now based on the triple point of water; redefining it in terms of k, or energy per degree of freedom, would link the kelvin to other SI units. Defining the mole in terms of the Avogadro constant means loosening the connection between the mole and the kilogram but, says Taylor, that “affects only chemistry, and chemists never need to know the molar mass of anything to better than parts per million.” And pegging the ampere to the elementary charge frees it from dependence on the kilogram—at present, the ampere is defined in terms of the force, in kg m/s2, between two infinitely long, parallel, current-carrying wires—and, together with tying the kilogram to h, would be a boon for electrical measurements, Taylor says.

For example, the Josephson constant 2e/h and the von Klitzing constant h/e 2 underlie practical measurement of voltage and resistance, respectively. Once those constants are exact, says Taylor, “you can realize electrical units exactly.” A host of other constants and conversions among different energy units also become exactly known, he adds. The only catch is that permeability and permittivity of free space, µ0 and ε0, become experimental quantities, he says, “but no one could care less.”

The other top candidate for redefining the kilogram links it to the Avogadro constant. Peter Becker of Germany’s standards lab says, “It’s sure that the experiment which reaches the best uncertainty will be the basis for the new definition.” But if the watt balance and the Avogadro experiment give similar uncertainties, he adds, “the question will be, Should we define the kilogram through the Planck constant or the Avogadro constant?” It’s conceptually more elegant and understandable to base it on atomic mass, he argues. “The definition will be taught in schools, and h is very abstract. We are collecting arguments in favor of the Avogadro definition.”

Either way, Taylor notes, the changes in the definition will not be noticeable in everyday life. “Customers in the supermarket will never know it happened. But it ties the units more explicitly to the invariants of nature, and the SI unit of mass will be realizable in different laboratories, not only at the BIPM. Hopefully, it will foster better understanding of the relations among constants. It might stimulate people to think of new experiments.”

To be considered at the 2011 General Conference on Weights and Measures, the international diplomatic body responsible for formally adopting any changes, new results have to be in hand by late 2010. “We have to make sure there is broad agreement,” says Quinn. “We are now embarking on a couple of years of intense discussion. It’s very exciting.”

The international prototype of the kilogram is 39 mm in diameter and 39 mm high. This is a copy of the actual reference standard.

BIPM/INTERNATIONAL BUREAU OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

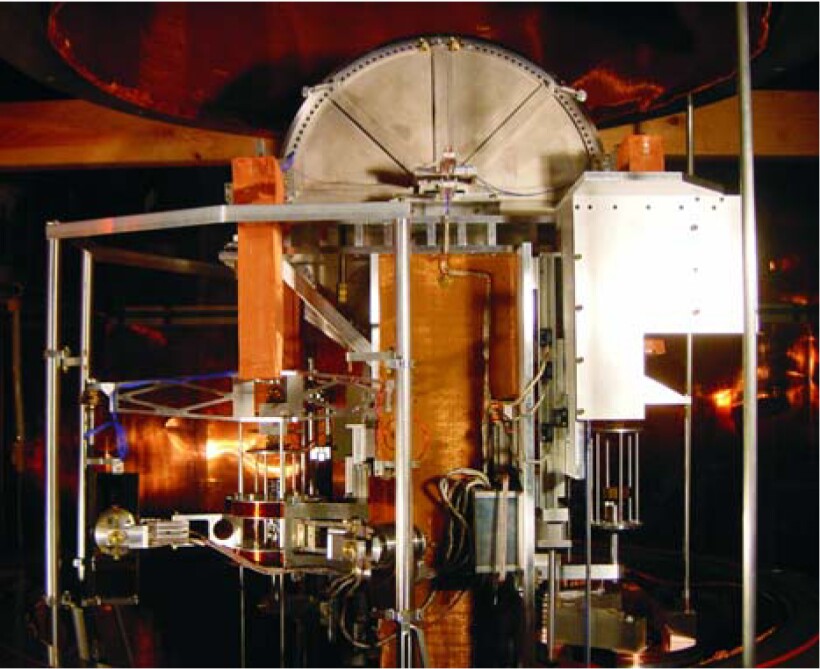

The moving-coil watt balance at NIST holds the record for relating a mass standard to the Planck constant. Of five such experiments worldwide, it’s the only one that uses superconducting magnets.

EDWIN WILLIAMS/NIST

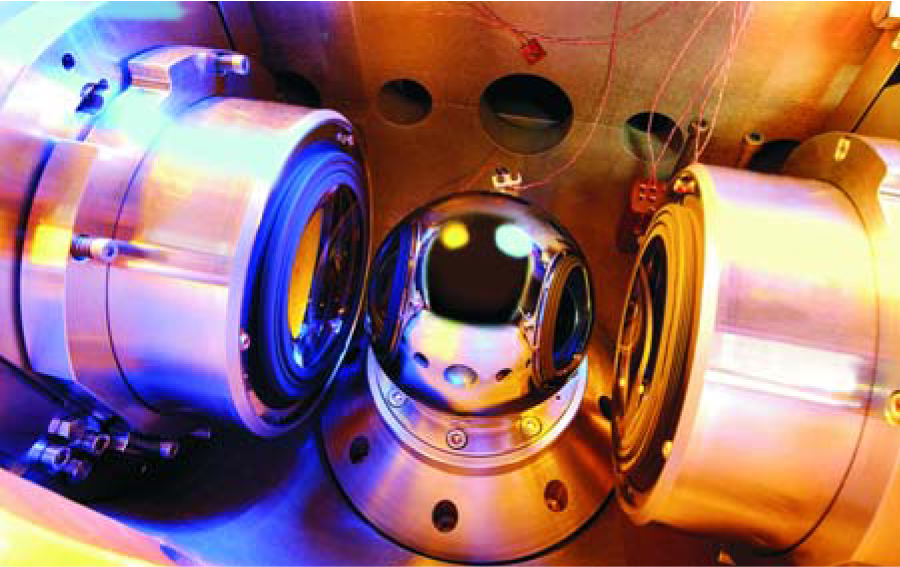

A 1-kg silicon sphere used for counting atoms is set up here to have its roughly 92-mm diameter measured interferometrically.

PHYSIKALISCH-TECHNISCHE BUNDESANSTALT

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org