Three crystallographers share this year’s chemistry Nobel

DOI: 10.1063/1.3273002

“This year’s prize,” announced Secretary General Gunnar Öquist, “rewards studies of how the DNA code is translated into life. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry jointly to Professor Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Professor Thomas Steitz, and Professor Ada Yonath.”

Translation is an apt metaphor. DNA and RNA, the bearers of life’s genetic blueprints, consist of strings of bases. Proteins, life’s principal building blocks, consist of strings of amino acids. Making proteins entails converting one molecular language to the other quickly and accurately. In all living things, from bacteria to baboons, the translator is the ribosome.

By the 1970s, molecular biologists had figured out what ribosomes are made of (a mixture of RNA and protein) and identified translation’s main steps, but they didn’t know the underlying chemistry. Because chemistry entails the exchange and sharing of electrons on scales of a few angstroms, understanding how the ribosome does its job requires determining its three-dimensional structure on those same scales.

Ribosomes differ somewhat from species to species, but each version is about 20 nm across. Only x-ray crystallography can yield the atomic structure of such biomolecular behemoths—provided, that is, one can make well-ordered crystals, obtain finely detailed diffraction patterns, and extract the atomic-level structure.

In 1980, after a decade of toil, Yonath of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, obtained the first ribosome crystals. 1 It would take a further two decades before improvements in crystal quality, x-ray detectors, synchrotron sources, and analysis methods made it possible to finally see the ribosome with atomic resolution.

Ribosome rudiments

The four bases that make up DNA come in two types. Adenine (A) and guanine (G) are purines; they each have two carbon-nitrogen rings. Cytosine (C) and thymine (T) are pyrimidines; they each have one carbon-nitrogen ring. That difference in molecular size informs DNA’s two-strand structure. When joined together, a purine on one strand always faces a pyrimidine on the other, and vice versa. Moreover, thanks to chemical compatibility, A always pairs with T and C always pairs with G.

DNA serves as a master copy of an organism’s genome. When it’s time to make a protein, the appropriate stretch of DNA is split open and the exposed gene is transcribed to a piece of single-stranded messenger RNA (mRNA). All types of RNA contain the same bases as DNA with the exception of uracil (U), which takes the place of the chemically similar T.

The genetic code consists of three-letter words or codons, each standing for one of the amino acids that proteins are made of. For example, GCA represents alanine; CAU, histidine. All 43 codons are used, despite there being only 20 amino acids. Some surplus codons encode the same amino acid. For example, ACA, ACC, ACG, and ACU all encode threonine. Other surplus codons serve as stop codons that demark the end of a gene. Special start sequences ensure that the codons, which abut each other without spaces or punctuation, are read correctly.

The role of associating a codon with its amino acid is performed by transfer RNA (tRNA). Thanks to its exposed sequences of bases, a strand of RNA can link to itself, forming pinched-off loops and DNA-style helices. A tRNA molecule has three pinched-off loops that resemble the leaves of a clover plant. The plant’s stem is the binding site for a particular amino acid. Opposite the stem, at the tip of the topmost leaf, is the anticodon: three exposed bases that are the complementary binding partners of the amino acid’s codon.

Not every codon/anticodon has a corresponding tRNA. Because the complementarity at the third letter doesn’t have to be exact, one tRNA suffices for an amino acid, such as threonine, whose several codons differ only in the third letter. Enzymes called RNA transferases attach the right amino acid to the right tRNA. At any given time, the 30 or so different tRNAs float freely in a cell. It’s the job of the ribosome to process them.

Ribosomes all have the same basic structure and function. Each ribosome consists of a small subunit and a large subunit. Although each subunit contains 20 or so distinct proteins, it is RNA, in the form of one long strand with loops and helices, that makes up the bulk.

When not engaged in translation, a ribosome’s two subunits are separated. The details of how translation begins differ in prokaryotes (microbes that lack cell nuclei) and eukaryotes (higher organisms whose cells have nuclei), but the principle is the same. With the help of various proteins, a small ribosomal subunit latches onto a strand of mRNA at an appropriate starting place. A large ribosomal subunit then binds to the small subunit, sandwiching the mRNA. Translation commences.

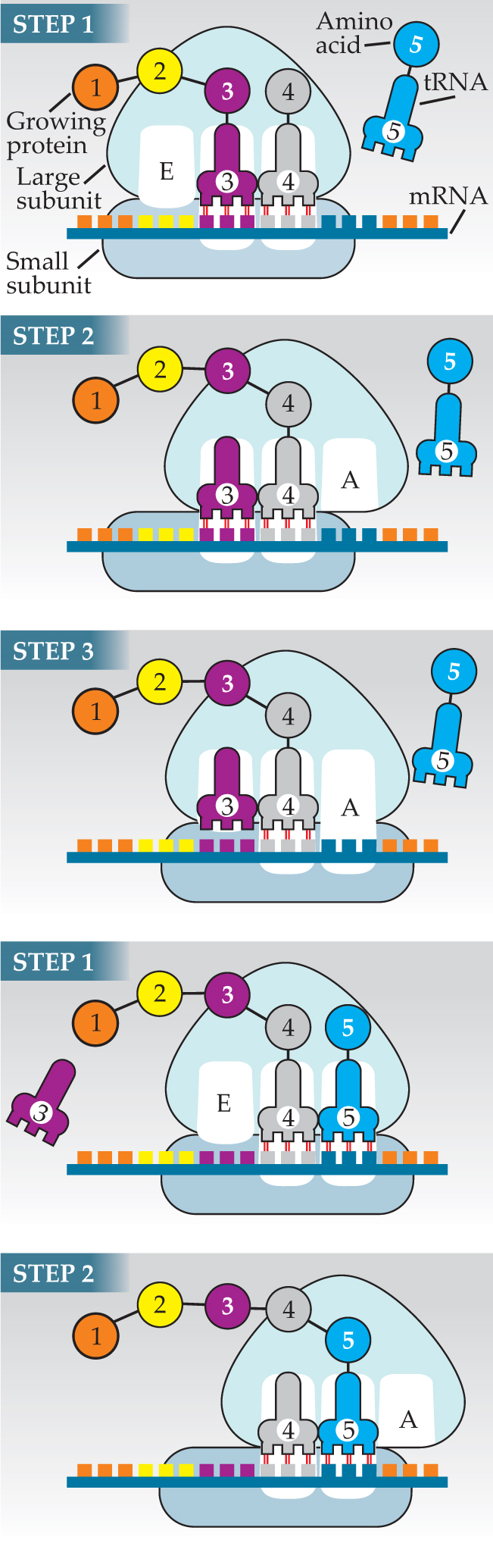

The large subunit has three sites for accommodating tRNA: A (for aminoacyl), P (for peptidyl), and E (for exit). Figure 1 depicts a ribosome as it’s about to add the fourth amino acid to a nascent protein. In step 1, a tRNA charged with an amino acid has found its way to the large subunit’s A site. The small subunit holds the codon corresponding to the fourth amino acid beneath the A-site tRNA. If, as is the case here, the tRNA’s anticodon complements the codon, the tRNA binds to the mRNA and remains in the A site. Next door in the P site sits the tRNA charged with the protein’s third amino acid.

Figure 1. Translation entails correctly matching the amino-acid-charged transfer RNAs (tRNAs) with the messenger RNA (mRNA) and adding the amino acid to the growing protein. The ribosome’s large and small subunits provide the site for translation as well as the catalysis required to speed the underlying reactions.

(Adapted from ref. 5.)

Two main things happen in step 2. The large subunit shifts with respect to the small subunit, repositioning the most recently arrived tRNA to the P site and its predecessor to the E site. During, after, or before the shift—the timing isn’t known—the large subunit catalyzes the removal of the third amino acid from its tRNA and its attachment to the fourth amino acid. The protein grows by one amino acid.

In step 3, the now uncharged tRNA in the E site leaves the ribosome and the small subunit shifts downstream to position the next codon in the now-empty A site to await the arrival of a new tRNA.

Hot-water bugs

The illustration in figure 1 represents roughly the state of knowledge in the 1980s. Molecular biologists knew what the ribosome does but not how it does it. For example, Francis Crick proposed the “wobble hypothesis” in 1966 to explain why anticodons and codons can tolerate a mismatch in the third letter. But exactly how the ribosome mediates that tolerance was unknown.

The answer to that question and others had to await the atomic structures obtained in 2000 by Yonath’s group, 2 and those of Ramakrishnan 3 at Cambridge University in the UK and Steitz 4 at Yale University. And before those structures could be obtained, someone had to crystallize a ribosome.

Yonath set herself that goal in 1970. At first she tried tackling the ribosome of the bacterium whose biochemistry is best known, Escherichia coli. When that tack failed, she switched to bacteria and archaea that live under harsh conditions, reasoning that their ribosomes could withstand the multiple traumas of extraction, purification, crystallization, and irradiation.

Having identified likely organisms, Yonath had to find optimal crystallization conditions. Nowadays, crystallographers use robots to fill thousands of tiny vessels with systematically different mixes of various promoters. Yonath mixed each combination by hand. Eventually, in 1980, she published her first success: crystals of the large subunit of Bacillus stearothermophilus, which lives in hot springs.

Even if those first crystals had been perfect, Yonath and anyone else who followed her recipes would not have been able to extract an atomic-level structure. The large and small subunits of the ribosome contain so many atoms that high x-ray fluxes and narrow beams are needed to yield a sufficiently clear and detailed diffraction pattern. Also needed is a method of ensuring the ribosome survives the intense irradiation long enough to cast a usable pattern. Third-generation synchrotrons, which came on line in the early 1990s, produced the requisite beams. Freezing the crystals, a technique developed by Yonath and Håkon Hope of the University of California, Davis, provided the requisite protection.

Advances were also needed in CCD detectors and structure determination algorithms. Solving crystallography’s notorious phase problem, however, did not require new methods. Nevertheless, applying the standard techniques, such as isomorphous replacement and multiple anomalous diffraction, was difficult for a molecule that was 10 times bigger than any attempted previously.

By the mid 1990s, when Steitz and Ramakrishnan joined Yonath’s ribosome quest, those technical hurdles had been surmounted. Figure 2 shows a sequence of structures determined by Steitz’s group, culminating with the 2.4-Å structure on the right. To reach that resolution, he and his group exploited not only the latest technology and techniques, but also structural information obtained from cryo-electron microscopy. Cryo-EM can’t yet yield true atomic resolution, but it can provide structural information without the need for crystallization. As a starting point for his 2.4-Å x-ray structure, Steitz and his colleague Peter Moore used a 20-Å cryo-EM structure derived by Joachim Frank of Columbia University.

Figure 2. This sequence of structure shows how important obtaining atomic resolution is. Only at 2.4 Å can one one see the helices of the RNA (gray) that form the bulk of the large subunit and the detailed structure of the ribosomal proteins (gold). The structures were obtained by Thomas Steitz and his collaborators in, from left to right, 1997, 1999, and 2000.

(Courtesy of Nenad Ban, ETH Zürich.)

Lessons learned

The atomic resolution structures immediately answered a fundamental question: Is the ribosome a ribozyme? That is, is the ribosome catalyst made of RNA? Biochemical evidence and low-resolution structures gave contradictory answers. Mutating ribosomal proteins slowed the ribosome’s activity, as if the proteins played a role in catalysis. On the other hand, the low-resolution structures didn’t show ribosomal proteins near the catalytic sites.

The atomic structures proved that, yes, the ribosome is a ribozyme. Only ribosomal RNA is found at the catalytic sites. As for the proteins, some of them have long thin tails that reach almost to the catalytic sites and bestow structural stability. Mutating them affected catalysis in so far as it loosened the ribosome’s structure.

Ramakrishnan’s group answered another fundamental question: How do ribosomes pick the right tRNAs? The part of the small subunit that mediates codon–anticodon pairing consists of a DNA-like helix. When the match is good, two bases in the helix flip out to stabilize the bonds between the first two letters. The base closest to the third letter doesn’t flip out. The lower degree of stability it provides accounts for Crick’s wobble.

Identifying how the ribosome catalyzes the growth of a protein chain was not clear from the atomic structure alone. But when combined with biochemical and computational evidence, the mechanism was shown to depend on the shuttling of a proton between the two tRNAs, which the ribosome helps by favorably positioning the tRNAs and by establishing a preorganized network of hydrogen bonds.

The structures and those that followed also provided insights into how certain antibiotics work. Erythromycin, for example, is used to treat respiratory infections in patients who are allergic to penicillin. Like other antibiotics, erythromycin prevents bacterial ribosomes from working, thereby condemning the bacteria to death as their proteins wear out without being replaced. Human ribosomes differ sufficiently from bacterial ribosomes that antibiotics don’t affect them.

This year, Rib-X, a company that Steitz cofounded, has just seen its first antibiotic phase II trials completed. The drug is designed to combat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Ramakrishnan was born in Chidambaram, India. He earned his PhD in 1976 from Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. He has been at Cambridge since 1999. Steitz was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He earned his PhD in 1966 at Harvard University. He has been at Yale since 1971. Yonath was born in Jerusalem. She earned her PhD in 1968 at the Weizmann Institute, where she continues to work.

Ramakrishnan

COPYRIGHT 2009 LABORATORY OF MOLECULAR BIOLOGY

Steitz

COPYRIGHT 2009 LABORATORY OF MOLECULAR BIOLOGY

Yonath

COPYRIGHT 2009 LABORATORY OF MOLECULAR BIOLOGY

References

1. A. E. Yonath et al., Biochem. Intl. 1, 428 (1980).

2. F. Schlünzen et al., Cell 102, 615 (2000).

3. B. T. Wimberly et al., Nature 407, 327 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35030006

4. N. Ban et al., Science 289, 905 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5481.905

5. B. Alberts et al., Essential Cell Biology: An Introduction to the Molecular Biology of the Cell, Garland Science, New York (1997).