The melting underneath the Thwaites Glacier is complicated

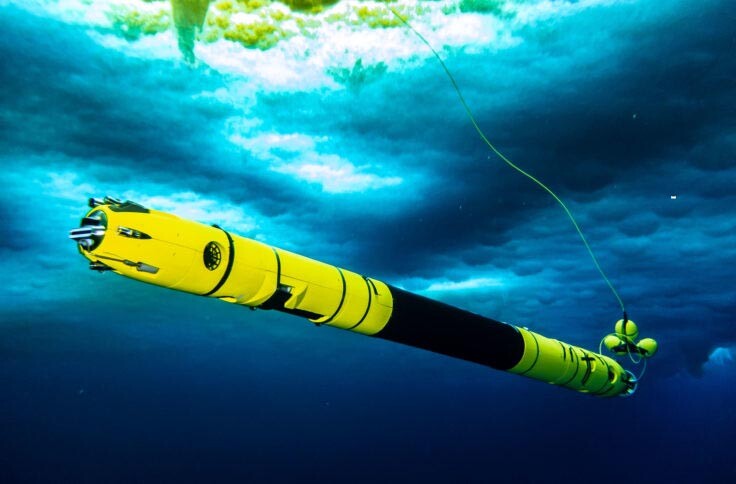

The robotic submersible Icefin is shown here underneath McMurdo research station in Antarctica.

Rob Robbins USAP

The Thwaites Glacier is one of the fastest receding ice masses in Antarctica, retreating by about 1 km/year. Because the depth to its base increases farther inland, it’s at a high risk of total collapse in the next several centuries, which would raise global sea levels by 0.5 m and around 3 m if it helps trigger a loss of the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet (see Physics Today, July 2014, page 10

Given the continent’s harsh conditions and remote location, most observations of the Thwaites Glacier have come from satellites, radar systems, and autonomous instruments. Those data, however, offer only a limited view of what’s underneath the ice and the processes that affect melt rates. (For more on Antarctica’s hydrology, see the article by Sammie Buzzard, Physics Today, January 2022, page 28

As part of the collaboration’s MELT project, researchers have now analyzed data collected from a conductivity, temperature, and depth profiler, which was deployed into a borehole drilled through the ice, and Icefin, a remote-controlled underwater vehicle, shown above. Findings from two simultaneously published papers show that although above-freezing water at the ice base is melting the Thwaites Glacier as expected, the rate varies substantially and unexpectedly depending on the topography, water density, and current speeds, all of which strongly vary with the measured location.

Over time, an ice base that slopes downward toward the land can exacerbate melting, steadily nudging the grounding line inland. The grounding line marks the boundary beyond which the glacier stops being supported by the land surface and where an ice shelf stretches over the ocean. As the grounding line retreats, more ice that was grounded flows into the ocean, causing sea levels to rise. And eventually, the entire ice shelf may become destabilized and collapse into the ocean.

Data from the borehole profiler and the nearby measurements collected by Icefin show water temperatures around −0.8 °C at the glacier’s base, warm enough to trigger melting. The water temperature and salinity steadily increase with distance from the ice.

The paper authored by Cornell University’s Britney Schmidt

Not only do the observations reveal heretofore unseen topography of the Thwaites Glacier, but they also act as critical benchmarks to evaluate ice models. In the absence of concrete data on the glacier’s basal conditions, modelers simulate melting ice assuming the ocean is well mixed. In that turbulence regime, melting rates—and by extension, sea-level projections—depend on a combination of the water’s flow velocity and its thermal forcing on the ice.

Under those assumptions, models would predict that the Thwaites Glacier is melting at a rate of 14–32 m/year, which is an order of magnitude higher than the 2–5 m/year predicted by the new work. In the paper authored by Peter Davis

More about the authors

Alex Lopatka, alopatka@aip.org