The gradual, then sudden, demise of an East Antarctic ice shelf

DOI: 10.1063/pt.uryu.shtv

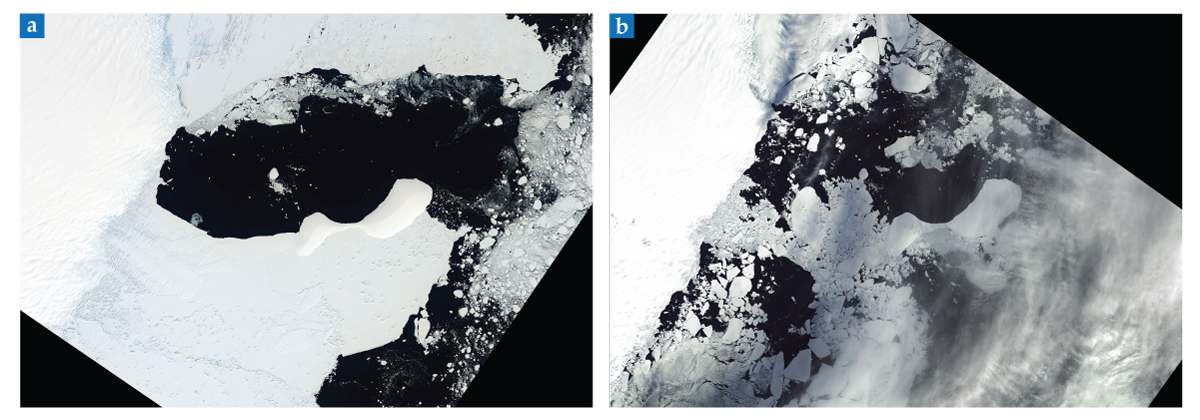

The Conger–Glenzer Ice Shelf, (a) although intact on 9 January 2022, (b) had shattered by 23 March 2022. The seemingly abrupt breakup was foreshadowed by a long period of ice thinning and crack formation. (Images by Lauren Dauphin/NASA Earth Observatory.)

In March 2022, Catherine Walker, of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, and her colleagues were poring over the latest satellite images of part of the Antarctic coast, when they noticed something alarming. A 1200 km2 ice shelf—not the one they were studying at the time, but one nearby—had abruptly shattered. Days later, it was all but gone.

The loss of an ice shelf isn’t an immediate threat. The ice is already afloat, so it doesn’t raise sea levels when it detaches from the continent, although it can destabilize adjacent land-bound glaciers. Moreover, the lost ice shelf, known as Conger–Glenzer, was not especially large; the Rhode Island–sized Larsen B, which collapsed in 2002, was 2.5 times as big. What made Conger–Glenzer’s demise concerning was its location. Larsen B was on the slender Antarctic Peninsula, where summer temperatures often rise above freezing. But Conger–Glenzer was in East Antarctica, a more reliably chilly region that also harbors the bulk of the continent’s ice mass.

The obvious culprit was an atmospheric river that had struck East Antarctica that season. Similarly to how they’ve been affecting the continental US and other temperate regions, formerly rare atmospheric rivers have increasingly been afflicting Antarctica with stormy weather and vast amounts of unusually warm precipitation. Still, Conger–Glenzer showed no signs of surface melting in the weeks before its collapse. Instead, the destructive force was wind, which churned the surrounding sea and stressed the ice shelf to its breaking point.

But now Walker and colleagues have dug deeper into the satellite record, and they’ve concluded that Conger–Glenzer’s demise wasn’t solely the result of a freak event. Rather, the ice shelf had been on the decline for decades. Its thickness decreased from 200 m in the 1990s to 150 m in the late 2000s. And in the late 2010s, it started to rapidly accumulate a network of large surface fractures. Those changes, among others the researchers noticed, left the ice shelf vulnerable to breakup when the storm of 2022 hit.

The glaciers that the Conger–Glenzer Ice Shelf had been stabilizing already appear to be flowing slightly faster into the ocean. But with the ice moving at a literal glacial pace, it’s far too soon to know what the long-term consequences will be. A better understanding of the signs that foreshadow an ice-shelf collapse could help researchers more accurately forecast Antarctica’s future. “We don’t actually have a good understanding of how ice breaks,” says Walker. “We have models of fracturing and melting, but we’re continually taken by surprise when these things happen.” (C. C. Walker et al. Nat. Geosci. 17, 1240, 2024

This article was originally published online on 20 December 2024.

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org