The crystal structure of a lower-mantle mineral

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2005

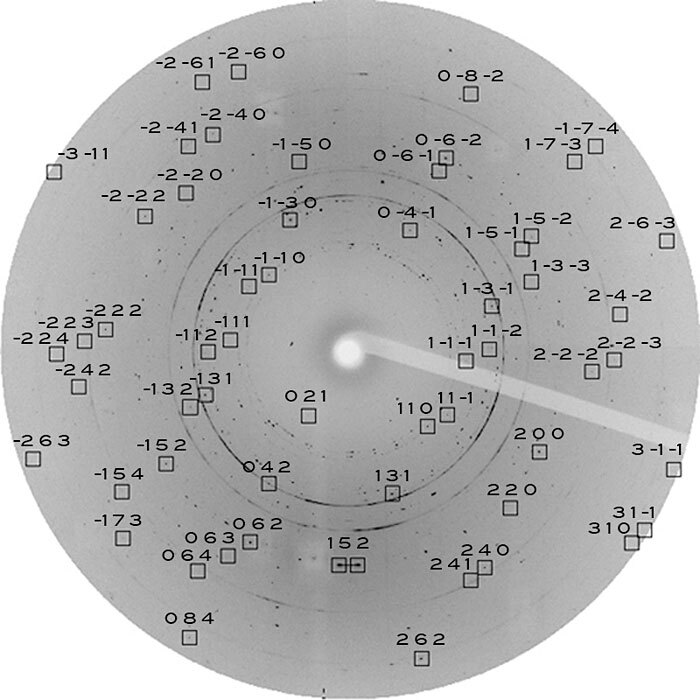

Just above Earth’s liquid outer core lies a 200-km-thick region, dubbed D″, whose properties differ from those of the rest of the mantle. Long a mystery, the origin of D″ became clear in 2004 when the most common mineral in Earth’s mantle, magnesium silicate (MgSiO3), was found to change its crystal structure at conditions that prevail in D″—that is, at pressures above 120 gigapascals and temperatures above 2500 kelvin. A new study by Ho-Kwang Mao of the Carnegie Institution of Washington and his collaborators sheds further light on the transition. Like their predecessors, Mao and his team used a diamond anvil cell to apply pressure, a laser to apply heat, and x-ray crystallography to determine structure. As the transition neared, a hundred or so randomly oriented crystallites of the high-pressure phase nucleated within the micron-scale sample. To gather enough structural information about the ensemble, Mao and team rotated the sample through 51° in 0.2-degree steps, yielding 256 sets of overlapping diffraction patterns (see figure for an example). A computer algorithm sorted through thousands of discrete spots to determine the crystallites’ orientations and structures. Besides confirming previous results, Mao’s study reveals that replacing 10% of the magnesium with iron barely alters the structure. An admixture of iron is expected in the lower mantle. Its lack of structural influence is encouraging, because it suggests that inhomogeneities in seismic data could be mapped to inhomogeneities in temperature and pressure, such as plumes and hot spots. (L. Zhang et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 6292, 2013, doi:10.1073/pnas.1304402110