Taking stock of the nanotechnology consumer products market

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2273

Children’s toys coated with antimicrobial silver nanoparticles and bicycle tires spiked with grip-improving carbon nanotubes are among the more than 1600 consumer products logged in the Nanotechnology Consumer Products Inventory (CPI). The free online database (http://www.nanotechproject.org/cpi

In the intervening years, the database grew, and it began to be criticized for not containing scientifically useful data. The CPI’s intended purpose was to stimulate discussion on the emergence of nanotechnology in commerce, but people were “misusing the information in the media and in peer-reviewed literature to make safety and toxicity claims,” says Kuiken.

So last fall, in response to those criticisms, the database received an overhaul, thanks to $25 000 from the Virginia Tech Center for Sustainable Nanotechnology, the Wilson Center’s new partner on the CPI project. Besides identifying the name of the product, manufacturer, and the nanomaterial ingredient, the database now includes scientific and safety information, such as the nanomaterial’s function and toxicity. Adopting a crowdsourcing model, the database invites registered users to upload relevant data from scientific literature and other publicly available sources.

Verifying the claims

Prior to the upgrade, many researchers in the Virginia Tech Center for Sustainable Nanotechnology used the CPI to find out what types of products and nanomaterials were entering the consumer market, says the center’s associate director, Marina Quadros. That information was then used to “identify new areas of research and to justify the need for further work assessing the environmental and human implications of nanotechnology.” The new CPI has search tags to “better describe the nanomaterials within each product, such as size and shape, composition, and location within each product, and the potential human exposure routes,” she says.

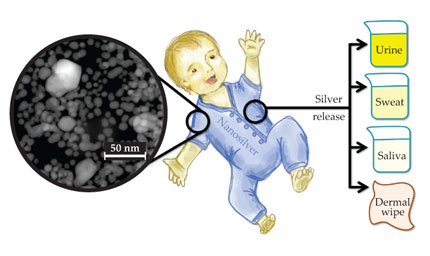

Touted as having antimicrobial benefits, nanosilver from fabrics, a plush toy, and other children’s products accumulates mostly in urine and sweat, according to a 2013 Environmental Science and Technology paper. Lead author Marina Quadros says she mined the Nanotechnology Consumer Products Inventory for some of the items used in the study, which was done in collaboration with researchers at the Consumer Products Safety Commission and the Environmental Protection Agency. (Adapted from M. Quadros et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 8894, 2013,

But according to the CPI’s own new data-quality rating—called “How much we know”—fewer than 10% of the entries currently provide supporting evidence that the nanomaterial works as claimed, or is even present in the product. One that does is an engine-oil additive under the “extensively verified claims” category, which identifies the nanomaterial (tungsten disulfide nanoparticle), its function (lubricant), its location in the product (suspended in liquid), and its potential human exposure pathway (dermal absorption and inhalation). The entry also includes quotes from research papers that validate the function and performance claims of the nanomaterial.

In contrast, the only information identifying the nanomaterial in a mountain-climbing ice axe found under the “unsupported claims” category is a quote from the manufacturer claiming that the product is made from a patented “Nanoflex” steel alloy that is “60% stronger than normal steel.” To make such data more reliable, the CPI “most needs the participation of contributors,” says Quadros. “In order to keep up with the fluidity of the consumer product market, we need help from manufacturers and researchers in updating the CPI data.”

Another criticism is that the CPI does not accurately reflect the size of the market. Given the website’s disclaimers, that criticism is unfair, says Duke University research scientist Stacey Frederick, who studies the impact of nanotechnology commercialization on industries and on geographic regions. “People were citing the number of products listed on the site as an official number of the market size, because there aren’t many other readily available sources to cite for this.”

Lists of shame?

In Europe, some consumer groups are also tracking products containing nanomaterials. In 2012 the Danish Consumer Council launched the Nanodatabase, which includes more than 1200 such products. Also in 2012, the European Association for the Coordination of Consumer Representation in Standardisation (ANEC) and the European Consumers’ Organisation (BEUC) published a database of 117 consumer products in the European Union market claiming to contain silver nanoparticles.

Unlike the CPI, the European databases explicitly seek to raise awareness of nanotechnology’s potential risks and to encourage government regulation. Products in the Danish database are color coded according to their potential risk to human or environmental health. (The CPI “refrains from making such judgment on the products because we seek active participation from manufacturers,” says Quadros.) The ANEC/BEUC collaboration urges the US and the EU “to set up an extensive mandatory reporting scheme of all nanomaterials used in all products available on the market”—already a requirement in France and one that Denmark is considering. One EU regulation already in place forces cosmetics manufacturers to provide the name of the nanomaterial—followed by the word “nano” in brackets—in the list of ingredients.

Government agencies in the US have been slower to act. The Consumer Product Safety Commission does not yet regulate nanomaterials, but it engages in environmental, health, and safety R&D through the interagency National Nanotechnology Initiative (see the report on NNI in Physics Today, September 2013, page 21

Not surprisingly, representatives from the private sector chafe at regulation. Steffi Friedrichs, director general of the Brussels-based Nanotechnology Industries Association, says her organization and its members do not support the idea of government-mandated reporting schemes. And the problem with the CPI and other inventories based primarily on product claims, she says, is that such databases contain “biased information” and “during the current debate on nanomaterial safety, [they] tend to unjustifiably turn into lists of shame.”