Some white dwarfs are older than they look

For more than a century, astronomers have studied populations of stars by compiling color–magnitude diagrams. Magnitude is a logarithmic measure of a star’s apparent brightness (i.e. brightness as seen from Earth. Luminous, nearby stars have small (sometimes even negative) apparent magnitudes; dim, distant stars have large apparent magnitudes. Color is the difference between a star’s magnitude as viewed through two different spectral filters. And stars emit radiation more or less like black bodies, so the bluer the color, the hotter they are.

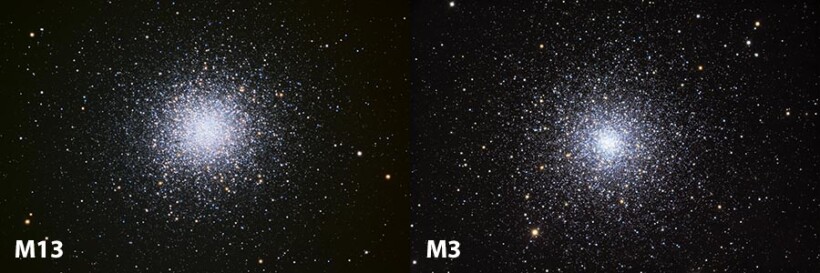

M13 and M3.

Sid Leach/Adam Block/Mount Lemmon SkyCenter, CC BY-SA 4.0

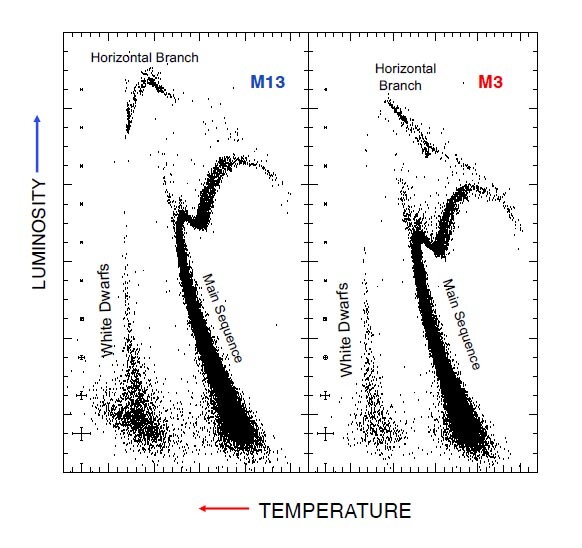

Francesco Ferraro of the University of Bologna in Italy and his collaborators have just published the color–magnitude diagrams of two globular clusters: Messier 3 in the constellation of Canes Venatici and Messier 13 in Hercules (shown in the images above). Because the observations were made with the Hubble Space Telescope, the diagrams are of unprecedented clarity. From them, the researchers deduced properties of the clusters’ white dwarfs.

A white dwarf is what’s left when a star with a mass up to about 10 times that of the Sun runs out of hydrogen and helium to burn. If the star were more massive, its own gravity would so squeeze the remaining oxygen and carbon that the elements would ignite. With thermal pressure restored, the star would resist further gravitational collapse. But in the absence of thermal pressure, gravity keeps squeezing the star until it’s so dense that electron degeneracy pressure kicks in and halts the collapse. The result is a white dwarf.

Francesco R. Ferraro

Without an ignitable source of fuel, a hot, fresh white dwarf is destined to cool and dim. As a white dwarf ages, its position in a color–magnitude diagram moves redward and downward. And that’s what Ferraro and his collaborators found in M3 and M13. White dwarfs of various ages were strung out in a narrow, near vertical strip at the bottom left of the diagrams (see figure).

Although M3 and M13 are similar in total mass, radius, and age, their distances from Earth differ: M3 is 34 000 light-years away; M13 is 22 000 light-years away. The difference in distance can be compensated for by shifting M3’s color–magnitude diagram upward in magnitude with respect to M13’s. If the two clusters’ stellar populations are similar, their color–magnitude diagrams should largely overlap.

Stars that belong to the main sequence—that is, ones that burn hydrogen in their cores—occupy a strip in the middle of a color–magnitude diagram. The main sequences of M3 and M13 did overlap after the shift, but the two populations of white dwarfs did not. Those in M13 appeared to be bluer and brighter than their counterparts in M3, as if they were younger.

What accounts for the apparent youth of M13’s white dwarfs? Ferraro and his collaborators propose that a small amount of leftover hydrogen continues to burn on the white dwarfs’ surfaces. The stars are not necessarily younger than their counterparts in M3. Rather, the extra source of heat means they take longer to slide down their track in the color–magnitude diagram.

Supporting evidence for the proposal comes from another difference between the two color–magnitude diagrams. The horizontal branch is a track occupied by stars that burn helium in their cores and hydrogen in their shells. Horizontal branch stars in M13 are bluer than the ones in M3 because of their slightly lower masses. This difference in mass affects those starts’ subsequent evolution and final fate.

Ferraro and his collaborators applied a widely used model of stellar evolution called BaSTI (Bag of Stellar Tracks and Isochrones). According to the model, the lower metallicity stars of M3 pass through a stage of life during which hydrogen in their shells is dredged inward to the core, where it burns. The higher metallicity stars of M13 skip the stage. When they eventually become white dwarfs, they have a supply of unburnt hydrogen ready to use.

Astronomers presume white dwarfs lack an internal source of heat and use the stars’ simple, predictable cooling as a clock to gauge the age of white dwarfs and their progenitors. Ferraro and his collaborators’ discovery adds a metallicity-dependent complication to that clock. (J. Chen et al., Nat. Astron., 2021, doi:10.1038/s41550-021-01445-6