Solid sorbent captures carbon

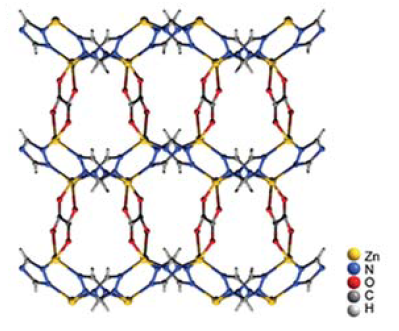

The metal–organic framework’s pore size enables it to reliably capture CO2 molecules.

J.-B. Lin et al., Science 374, 1464 (2021)

The promise of burning energy-dense fossil fuel without spewing its harmful byproducts into the atmosphere has motivated R&D in carbon capture and storage (see Physics Today, January 2022, page 22

Only a handful of power plants in operation today use carbon capture technology. They rely on chemical solvents that react with the gaseous waste stream after the fossil fuel is combusted. The chemical removal of CO2 from the flue gas is effective, but regenerating and recycling the solvents is energy intensive. Fresh solvents can replace old ones, but that’s costly and slows down operations.

A new class of sorption technology uses solid materials, one of which is the well-studied class of materials known as metal–organic frameworks, or MOFs (see, for example, Physics Today, June 2017, page 16

Now a collaboration of academic researchers and industry scientists has developed a MOF that’s suitable for capturing CO2. The team—led by Pierre Hovington (Svante Inc, Vancouver, Canada), Arvind Rajendran (University of Alberta), Tom Woo (University of Ottawa), and George Shimizu (University of Calgary)—tested the MOF in various conditions and found that it preferentially absorbs CO2 rather than water and retains its effectiveness in conditions with up to about 40% relative humidity.

The researchers crafted a zinc-based MOF with 38% of the volume composed of empty space, or pores. The critical part of the MOF is the center of the pores, which each have a strong binding site for CO2. The size of those pores, however, is small enough that water molecules don’t readily form hydrogen-bonded networks. The MOF isn’t meant to be used once: During a heating cycle, it releases the CO2 it absorbed and is then ready for another capture cycle.

Testing in various conditions showed that those properties make the MOF particularly effective at capturing CO2. In high-temperature flue gases over a six-day period, the MOF lost just 1.3% of its sorption capacity. And over a 2000-hour trial, including steam treatment and drying, the researchers found no appreciable performance loss. Additional experiments in more humid conditions showed a preference of the MOF for CO2 over water. About a year ago, Svante deployed the new MOF in one of its carbon capture systems at a cement plant, and the MOF has been trapping about 1 ton of CO2 per day.

The materials to make the MOF and the efficiency with which it can be produced also appear to be competitive against other sorbents. The oxalic acid and triazole used to produce the MOF, for example, are inexpensive and widely available. Zeolites—an aluminosilicate mineral commonly used as commercial sorbents—can be synthesized at a rate of 50–150 kg in a cubic meter of space per day. Laboratory production trials of the new zinc-based MOF, on the other hand, yielded about 550 kg/m3 per day. (J.-B. Lin et al., Science 374, 1464, 2021

More about the authors

Alex Lopatka, alopatka@aip.org