Recipe for LHC Success: Subtract Other Science, Add Accountability

DOI: 10.1063/1.1510275

Detailed spending records, revamped managerial responsibilities, redeployment of workers, contingencies for unexpected costs, and better communication. That’s the prescription of an external review committee (ERC) set up to investigate the ills at CERN after the Geneva-based laboratory revealed last fall that the Large Hadron Collider, a proton accelerator awaited by particle physicists everywhere, will exceed its budget by 850 million Swiss francs (roughly $574 million).

While placing blame for CERN’s current financial predicament squarely on the lab’s managers, the ERC praised the staff as “competent and dedicated” and underscored its confidence in the technical soundness of the LHC. Curtailing other scientific activities to focus on the LHC, the committee’s report says, “is the price to pay for the future possession of this powerful tool.”

CERN will take the medicine. Indeed, the committee’s recommendations, which were presented in June, are in tune with proposals developed by CERN management and five internal task forces for getting the LHC back on track. “The ERC made its report, and I am quite satisfied,” says CERN Director General Luciano Maiani. By the end of the year, Maiani says, “we will reshape the structure of reporting lines of the LHC.” CERN will also revisit the LHC’s tight construction and costing schedules.

Among the measures already being implemented are the inclusion, for the first time, of staff salaries in cost calculations. Excluding those salaries introduces a bias when weighing whether to do a job in-house or to outsource it, says Robert Aymar, who chaired the ERC and heads the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor. “It can induce the wrong decisions and cost you a lot.” CERN is also introducing a detailed accounting scheme whereby it will frequently check money spent against projected costs and incremental achievements.

These and similar measures—the ERC made some 20 recommendations—are intended to keep CERN tightly focused on successfully completing the LHC. The actual cost overruns will be covered through industry-related delays in the LHC’s startup by two years, until 2007; by slashing non-LHC programs; and by drawing out payment of the LHC until 2010. For example, CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron and Proton Synchrotron will be used less, and will then be shut off for at least a year beginning in 2005. Some engineers and technicians from those accelerators will be transferred to work on the LHC.

The new measures, says Maiani, “are the realization of how the lab has to cope with the famous [budget] cuts made in 1996. I hope we will have a new common basis between the council, the CERN management, and CERN people. It was not easy to get there, but we are really aiming to go forward.” (See Physics Today, February 1997, page 58

Prioritize and sacrifice

“The real plus was that everyone agreed that this is what needed to be done,” says Ian Halliday, who heads the UK’s Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council and is a delegate to the CERN council. “CERN is squirming, but they’ve accepted [the ERC’s recommendations]. It’s not a solution to the lateness. Not to the overruns. But at least we are beginning to get a clear picture. It’s a first step.”

CERN, adds Halliday, “[has] been told for six years now that the LHC is the priority. Cash is king—if other things are sacrificed, then so be it. Or raise money from elsewhere. Some [at the June council meeting] said it’s a shame. Others said you have to prioritize. Both are true.”

Indeed, what’s changing at CERN is that the LHC is not only called the priority, it’s now getting red-carpet treatment. The obvious and painful sacrifice is non-LHC research. One victim of the cuts is R&D for future particle physics facilities. Research on CLIC, a candidate for a next-generation linear collider, will continue, says Maiani, but at a minimal level. CERN hopes to fill this gap by working with other European high-energy physics labs.

As for other research, says CERN physicist Rolf Landua, “we realize that the LHC equals the future of CERN. We have to say, ‘My interests may be different, but if we don’t get the LHC going, then there is no future to discuss.”’ For his own group, Landua says, “Let’s try to get out of the crisis in the best possible way, and to do whatever we can to keep a tiny niche of antimatter research alive.”

But many CERN staff members and users have reacted to the plan with “discouraged resignation,” says CERN theorist Alvaro De Rújula. “Slashing both research and R&D may be suicidal. We may lose our scientific worth to a circumstantial policy, the way we lost much of our technical excellence to outsourcing requirements.” Michel Spiro, who heads particle physics and astrophysics research at France’s Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) and was just elected to CERN’s scientific policy committee, adds, “I hope that some budget and human resources will be available to react and fertilize new ideas that come from the particle physics community. To see a big lab like CERN, which is very creative, focus on just one project until 2010 is a bit frightening.”

CERN

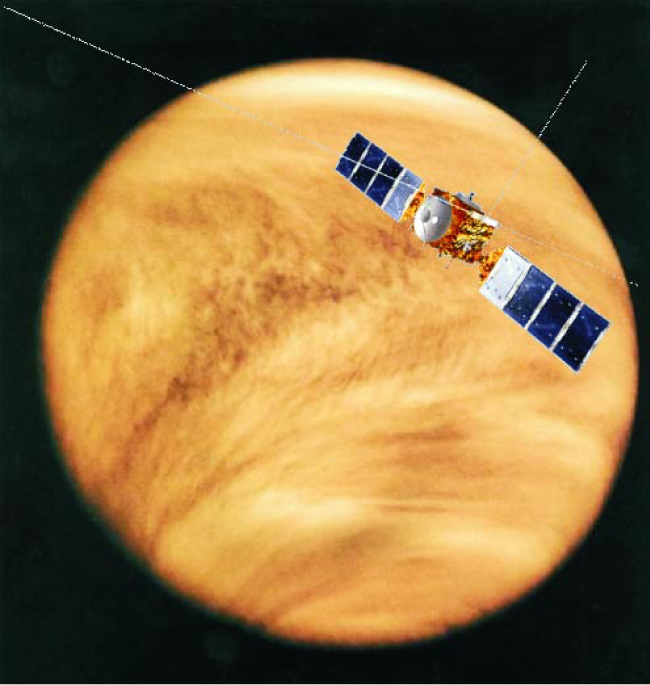

Luciano Maiani, CERN’s director general, and the lab’s governing council have agreed on a strategy for dealing with the financial crisis bedeviling the Large Hadron Collider (top), under construction beneath the French–Swiss border.

CERN

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org