RAPTOR Hunts for Celestial Flashes

DOI: 10.1063/1.1506743

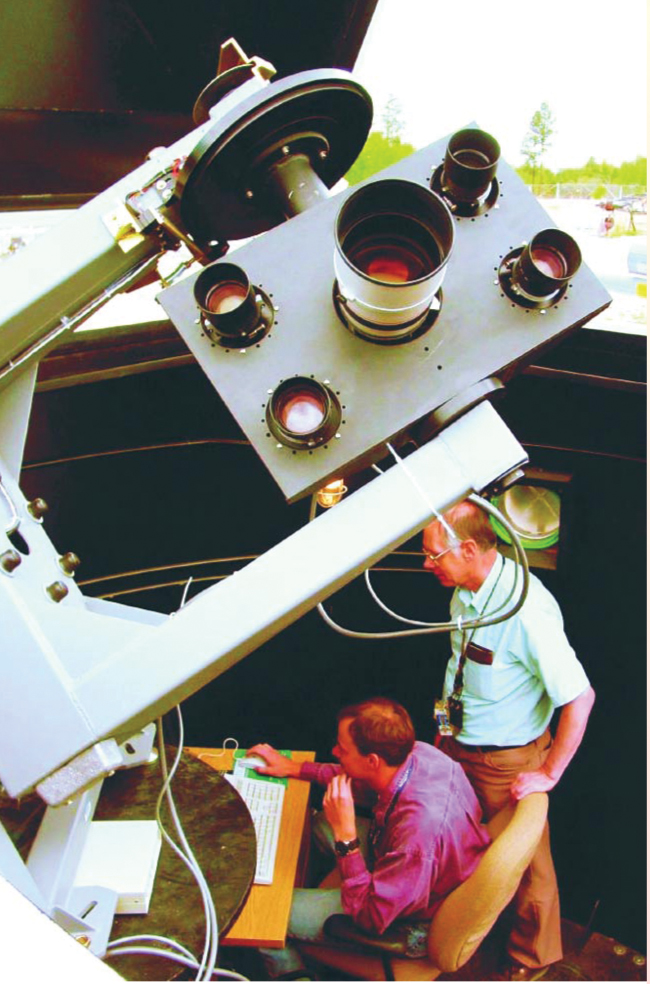

Anew bird of prey is scanning the skies in New Mexico: RAPTOR (Rapid Telescopes for Optical Response), a binocular robotic telescope developed by scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory, hunts for optical transients. One of its eyes is at the lab and the other is located 38 km to the west at Fenton Hill Observatory.

Unlike the ongoing and upcoming ground-based telescope projects that are triggered by satellite signals (see accompanying story), RAPTOR is self-triggering. It scans a 40×40° swath of sky and focuses in on transients. “It’s like human vision,” says project leader Thomas Vestrand. “We have a wide field of view, and when we want information about something in particular, we slew our eyes and put the foveae on the part we are interested in. The same with RAPTOR.”

RAPTOR seeks objects that change or move on timescales of a minute to more than an hour. “A perfect example that things like this exist is the famous optical burst from GRB990123,” says Vestrand. “Gamma-ray bursts as bright as that are not common, but there could be other things. And at the moment we have no way of knowing they’re there.”

Each RAPTOR telescope consists of an array of four camera lenses for scanning the sky, plus a fovea camera for zooming in on specific objects. The cameras are sensitive to 16th magnitude (some 10 000 times better than the naked eye) and each has a different color filter. “We want to get good spatial resolution, take images at a fast cadence, and get color information,” says Vestrand. Consecutive imaging, combined with checking for parallax shift from the binocular system, is used to verify that an object really is a celestial flash and not, for example, an image defect or a reflection off of space junk. Says Vestrand, “Nobody else is monitoring a significant chunk of sky to this sensitivity. Nobody else is doing this closed-loop thing—finding optical flashes, and following up, without human intervention.”

Hardware for the telescopes costs about $250 000 a pair, even with some parts bought on eBay, says Vestrand. Developing the software to run RAPTOR, he adds, “probably cost more than $1 million. The real heart of this is being able to handle the large database and detect changes—building the brain, if you will.”

RAPTOR (Rapid Telescopes for Optical Response) scans the skies and focuses on optical transients. James Wren (seated) and Don Casperson are among the dozen or so Los Alamos National Laboratory scientists involved in RAPTOR.

THOMAS VESTRAND

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org