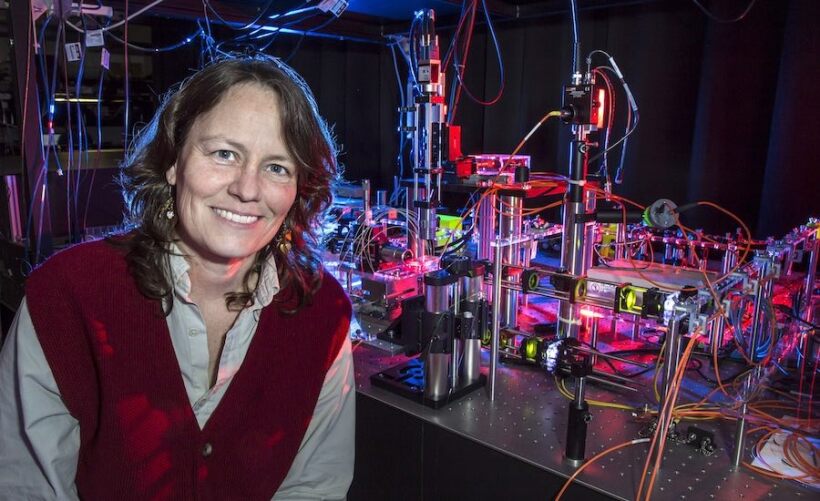

Q&A: Cather Simpson, founder of New Zealand’s powerhouse Photon Factory

University of Auckland

Standing in front of her poster at her first-ever scientific conference, Cather Simpson was pumped. It was around 1990, and Simpson, then an MD/PhD student at the University of New Mexico, was excited to share her results. So, with big names in cell biology crowded around, she was dismayed when her adviser grabbed the limelight and didn’t introduce her as the one who had done the work. Then Simpson got a shock: She heard her adviser lie about having done certain control experiments.

Later that night, she got another shock when she confronted her adviser. “Oh, no, we never got that control experiment to work,” the adviser said, “but I know how it would have turned out.” Simpson quit the lab. (She told her story on the 26 January edition of the Story Collider podcast

In her new field, Simpson discovered the passion that has driven her science ever since. “I wanted to understand how molecules decide what to do with the energy that they absorb in the form of light,” she says.

Simpson moved from the US to New Zealand in 2007 to become a professor of physics and chemical sciences at the University of Auckland. Two years later she founded the Photon Factory, which has quickly become a magnet for students and a hot spot for ideas and spin-off companies. She says there are estimates that the lab’s R&D will raise New Zealand’s GDP by 0.2%.

PT: How did you get into science?

SIMPSON: I took a class in cell biology during my first year at the University of Virginia. The professor, Richard Rodewald, invited me to come work in his lab for the summer. I said yes, thinking it would look really good on my med school application. But I fell in love with science.

Later, as an MD/PhD student, I realized I didn’t have the right people skills to be a doctor. The aha moment for me came during an examination of a mock patient. I said something along the lines of “Oh, you have the coolest leukemia!” I heard the medical people in the room gasp, and I realized what I had just said.

I had become very interested in the scientific side of medicine. That helped me realize that the clinical side wasn’t really for me.

PT: How did you make the switch into chemical physics?

SIMPSON: When I left the lab where I was encountering troubling challenges around ethics, I hid out in a different part of the university for a while to avoid the fallout. I went to work in a chemistry lab. It turned out that what my new adviser did was very exciting.

PT: Can you elaborate on the ethical challenges? Was the lie at the conference the only issue?

SIMPSON: No, it wasn’t. That kind of thing never happens in isolation. We had been having arguments in lab meetings about when to toss out experimental results as faulty. To me, it seemed like we were ignoring data because they didn’t fit with our models. I remember we did one experiment seven times until we got a four to three ratio in the right direction. That sort of thing was disconcerting to me. I even asked not to be included on a paper. The lie at the conference was the last straw. At the time it seemed like this tremendous moment, a lie that thundered around the world. It clarified for me how wrong things were and showed me that I needed to get out.

PT: Any idea why you were more bothered by these things than others in your lab?

SIMPSON: I grew up in a US military family, where you don’t lie, you don’t cheat. You use words, like honor and glory, that you don’t often see elsewhere in society. That part of my background was what made me think that the things I was seeing in the lab were unethical.

And also Professor Rodewald, my first science mentor, really instilled in me the sense that science is about the search for truth. If we got a bad result in our experiments, something that didn’t fit with the hypothesis, he changed the hypothesis. You let the science take you to where it’s going to go, rather than trying to fit the science you do to some preconceived notion.

PT: Was switching fields difficult?

SIMPSON: I didn’t mean to change fields. I intended to do rotations through other biology labs when the brouhaha calmed down.

In the new lab, I started messing about with lasers. I had no experience with chemistry or physics and very little with mathematics. I had a great time learning the mathematics, quantum mechanics, and thermodynamics, picking up on all that stuff.

In retrospect, the moment I changed fields was when I came up with a hypothesis about what happens when the heme molecules in your blood absorb light—how they don’t photodegrade but rather dissipate that energy as vibrations, essentially molecular-scale heat. My adviser said, “You’ll never be able to measure that. It happens too fast.” I said, “Of course I will, and I bet you a pitcher of beer.”

I spent the weekend in the dark, taking the spectrum of my own hemoglobin molecules, and I won my pitcher of beer. All of a sudden I realized I had discovered something new, important, and unexpected: The hemes that make your blood red are surprisingly light-hardy. I was off.

PT: Where did you go from there?

SIMPSON: After I finished my PhD, I got a postdoc at Sandia National Laboratories. By then I knew that I wanted to study how molecules turn light into more useful forms of energy. Light is a way to move energy around: Vision is all about a molecule in your eye turning light into mechanical motion; in plants, photosynthesis is just about turning light into a little-bitty battery; and in your skin, hemes absorb light and turn it into molecular-scale heat.

I got a tenure-track job at Case Western Reserve University in the chemistry department. I set up a laser lab to study these energy and dynamics puzzles at the fundamental level.

PT: So how did you land in New Zealand?

SIMPSON: I had just gotten tenure, and my partner and I were having those horrid two-body problem conversations. You know, who is going to give up what for the career of the other? He got an offer in Auckland in the English department that was a huge step up, and I took a parallel step.

PT: Tell me about the Photon Factory.

SIMPSON: It’s a laser facility whose core mission is to help research and development for all New Zealanders—everyone from scientists and engineers to universities and companies to schoolchildren. We use our exotic, very short duration [roughly 100 femtosecond] laser pulses to do fundamental science and to help industry. Most of our government funding—$25 million NZD [$18 million] so far—comes from the Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment to do research in laser micromachining: cutting, making, and shaping things with our extremely short laser pulses.

We’ve made advances in laser surgery of bone and air-quality sensor chips. We are also studying how pigments fade in art, testing molecules that might help cure cancer using light, and exploring basic laser–material interactions.

We have 50 students and staff from engineering chemistry, physics, and biology. In New Zealand, undergraduates don’t usually do research. But since I didn’t know that when I arrived, a good number of our team members are undergraduates, and some have published significant first-author papers. Almost everyone does fundamental stuff, applied stuff, and entrepreneurial stuff. I very strongly believe that you can’t do good applied research unless you do basic research as well.

PT: What kind of commercial applications have resulted from work at the Photon Factory?

SIMPSON: We have two spin-off companies and a third one on the way. The first uses a laser to sort sperm by sex for the dairy industry. My favorite elevator speech starts with “I’m passionate about lasers—and sperm.”

The company uses microfluidics and photonics to allow dairy farmers to choose whether they have male or female offspring in their dairy cows. Earlier methods, with flow cytometry, are expensive, require expert technicians, and damage sperm. We use one laser to orient sperm cells, a second to do fluorescent measurements to distinguish cells carrying X and Y chromosomes—the males are slightly less bright because the Y chromosome is slightly smaller than the X chromosome—and a third laser to separate them.

India, for example, has 45 million dairy cows, but it takes three Indian cows to make the same amount of milk as one New Zealand dairy cow. That’s because they haven’t used artificial insemination a lot. With our technology, they could accelerate genetic gain through the use of artificial insemination. That would provide Indian families the same protein source with one-third the cattle. The reduction of dairy’s environmental impact would be amazing.

The other spin-off we call point-of-cow diagnostics. It looks at milk composition for every cow at every milking. So a farmer can learn about the productivity, the nutritional status, and the health status of every cow in their herd. They’d like to know, say, that Bessy is their highest protein producer. Or that Buttercup has an udder infection. Right now what farmers see is the herd-level average.

PT: Are you concerned about the gender-typing technology being used with humans?

SIMPSON: It can be used for humans, but we are not planning to go in that direction because of the ethics. There are some reasons for doing sperm sorting for humans—there are X-linked and Y-linked diseases. As soon as you can identify a disease genetically, you can test for it and get rid of it. But it’s a bit of a slippery slope.

PT: It sounds like, in some ways, you have come full circle in terms of working in medical-related areas and in terms of ethics. Have you had to deal with ethical issues as a professor?

SIMPSON: You see ethical issues with students cheating and plagiarizing everywhere, so yes. I like the University of Auckland’s system. If a student cheats in any way, shape, or form, the first offense goes into a registry in a sealed envelope. The envelope never gets opened, and it gets thrown out when the student graduates if he or she never gets caught again. I think that’s okay. I recognize that people make mistakes. I believe in redemption.

PT: What are your plans?

SIMPSON: We are looking to take the Photon Factory to the next level. I would like to see other academics be able to build their careers in the Photon Factory, using our facilities and our people, but without working directly for me. I’d like for the Photon Factory to become a kind of innovation hub.

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org