Putting holes in a sail to reach the stars

DOI: 10.1063/pt.ucrb.odut

Figure 1.

A high-powered laser on Earth could provide enough momentum to propel a simple light-sail spacecraft to Alpha Centauri in as little as 20 years. (Image adapted by Jason Keisling from L. Norder et al., Nat. Commun. 16, 2753, 2025

The Planetary Society, a nonprofit space organization, in 2019 launched a solar-sail-powered spacecraft that orbited Earth. Its reflective mylar sail used only the energy of solar photons to push it through space. The society demonstrated that solar-powered light sails can work locally, but more energy is needed for them to quickly travel greater distances. A high-powered laser fired for less than an hour from Earth’s surface could provide enough momentum to accelerate a sail to a fifth of light speed and reach Alpha Centauri within 20 years (see figure

Photons reflect off the sail, which is then propelled because of conservation of momentum. But as the sail picks up speed, the laser light becomes Doppler shifted. To reflect for as long as possible—and accelerate as much as possible—before getting out of range of the laser, a sail needs to reflect across a range of wavelengths. When designing the latest sail, Richard Norte (Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands) and his group targeted a range of 1.55–1.86 µm, where atmospheric absorption is low. That wavelength window provides a wider range than other theoretical designs so as to account for the Doppler-shifted wavelength of the proposed laser. Thus, the sail has lower reflectivity over a wider waveband compared with designs that have high reflectivity within a narrower waveband.

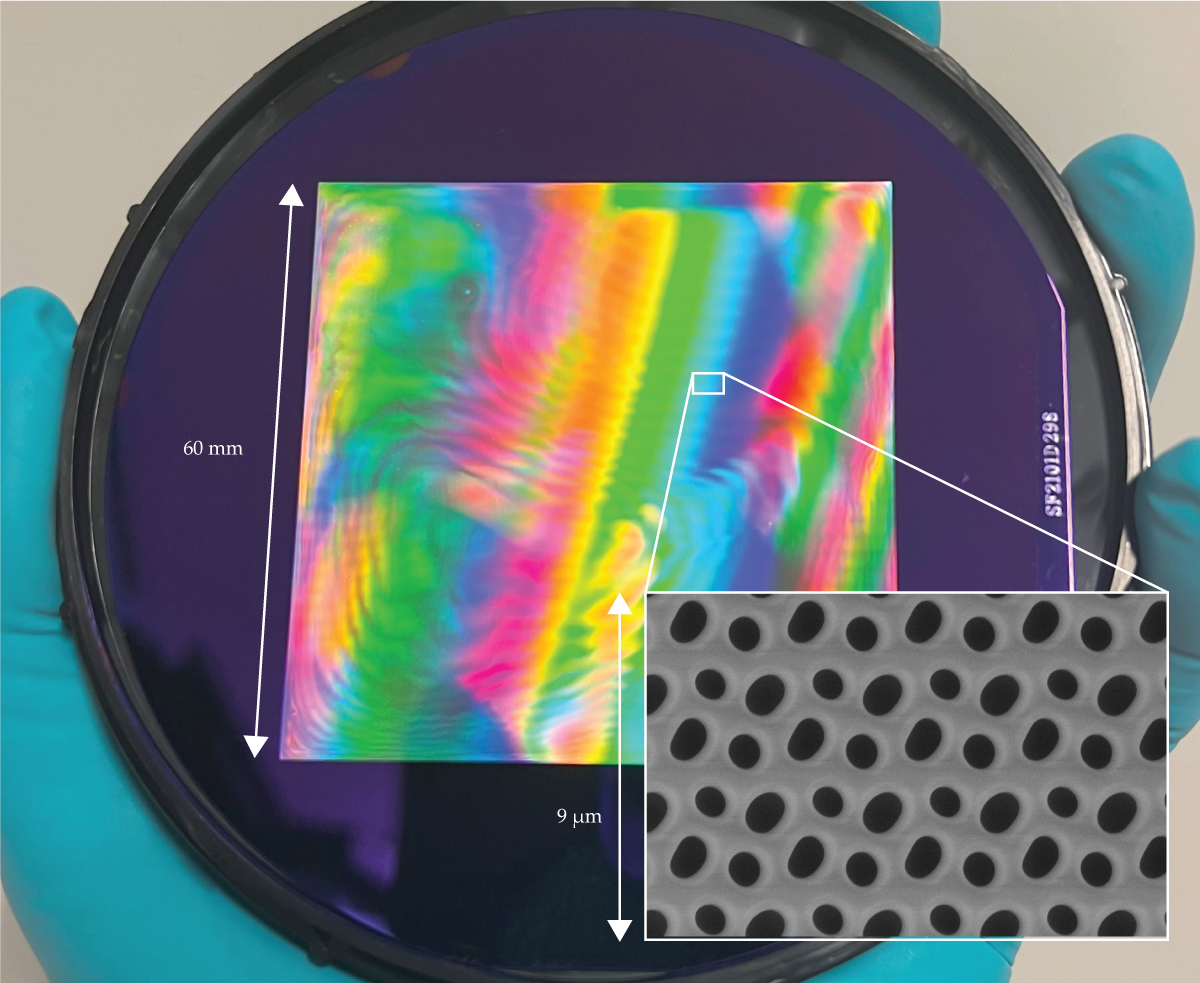

To reach relativistic speeds, the payload and the sail need to have masses of no more than 1 g each. The ultimate goal is a microchip payload carried by a 10 m2 sail, so the material needs to be lightweight yet strong. Previous light-sail designs have been multilayered to increase the broadband reflectivity at the expense of mass. Norte set his sights on a single-layer silicon nitride photonic crystal with subwavelength holes in the membrane that would determine what wavelengths are reflected. To design the pattern of holes, Miguel Bessa (Brown University in Rhode Island) used neural topology optimization to balance ideal hole sizes and arrangement for precise reflection against real-world manufacturing constraints. The result was a configuration featuring potato-shaped holes with slightly varied forms and sizes (see the inset in figure

Figure 2.

This 60 × 60 mm sail membrane has a repeating pattern of potato-shaped holes, as seen in the inset, imaged by a scanning electron microscope. Different hole sizes reflect different wavelengths of light, which allow the sail to continue reflecting laser light even when it is Doppler shifted. (Image adapted from L. Norder et al., Nat. Commun. 16, 2753, 2025

The pentagonal lattice pattern of holes lends strength to the membrane because its homogeneity creates a stable, crack-free suspension when unfurled. The repetitive pattern mask used to create the holes also reduces the manufacturing time of their 60 × 60 mm sail when compared to hole-by-hole fabrication. Although many technological advances are still needed before the meter-scale sail can be created, the thin sail material is projected to require a drastically reduced manufacturing time and be a promising final design for future light sails. (L. Norder et al., Nat. Commun. 16, 2753, 2025

This article was originally published online on 30 April 2025.