Planetary Astronomers Worry About Future Funding

DOI: 10.1063/1.1554127

NASA has no business in ground-based astronomy. That sentiment, repeated often by Edward Weiler, the agency’s associate administrator for space science, is nothing new. But it’s getting stronger, say some US planetary astronomers, and despite the first budget hike in a decade, they fear for the future of their field.

Their fears were triggered by Weiler’s rebuff this past fall of a recommendation, in the first-ever Solar System exploration decadal survey, that NASA be a key partner in the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope. High on the wish lists of the planetary and astrophysics communities alike, the roughly $170 million LSST would scan the same large swath of sky to 24th magnitude every five days or so. The telescope would be a dark-matter probe and a data trove of dynamic bodies such as supernovae, Kuiper Belt objects, and asteroids. “We’ve never looked at the sky in this way,” says David Jewitt of the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy. “What makes the LSST different is the huge field of view. Keck and other telescopes can go deep, but not over the whole sky. [The LSST] is almost certain to change the way we do astronomy. [NASA] should be jumping all over this and trying to make it happen. Instead, they are saying this is not their area.”

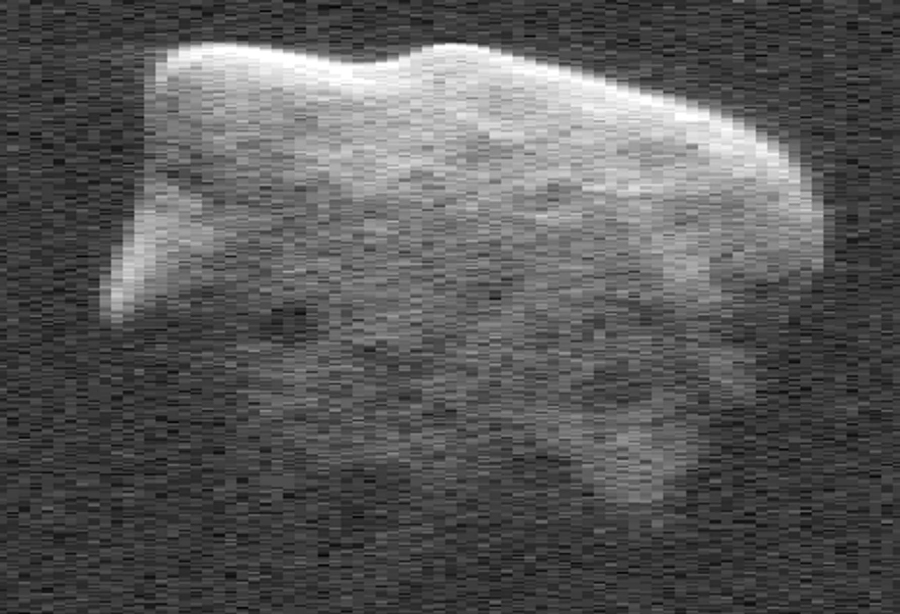

Compounding planetary astronomers’ concerns was NASA’s announcement in late 2001 that, as of the new year, the agency would cease paying for the planetary radar program at the NSF-owned Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Radar is one of the most powerful ground-based probes for studying nearby asteroids and comets, and news of the sudden cut prompted an uproar. But, says Weiler, “Why should we pay NSF to use their facility? We don’t charge them to use the Hubble.” John Hillman, who manages NASA’s planetary astronomy and atmosphere programs, adds, “NSF really loves the science that comes out of that radar program. Both [NSF and NASA] need it. NASAhas been paying for [the radar program] out of an ever-dwindling budget. NSF’s budget is growing like a bandit.” In the end, NASA temporarily restored funding, and the two agencies are close to an agreement under which, over the next few years, NSF will absorb the radar program’s roughly $600 000 annual operating costs—about 6% of NSF’s budget for the observatory.

Domino effect?

The Arecibo affair and the LSST rebuff, plus the chopping of individual grants have “people worried about a domino effect,” says Mike Belton, who chaired the Solar System exploration decadal survey. “It’s pretty clear that if Ed [Weiler] doesn’t take our recommendation [for the LSST] seriously, that might propagate to other areas.” One LSST priority would be to detect near-Earth objects down to 300 meters in diameter, extending the congressionally mandated “Spaceguard goal,” under which NASA is hunting for 90% of objects 1 kilometer in size or bigger that could potentially crash into Earth. To do that, says Belton, “you need specialized software. We felt this was a big job. And we felt it was important for NASA to be involved, just to be sure its objectives are actually achieved.”

The first item in NASA’s mission statement (see http://www.nasa.gov

As precedent, planetary astronomers point to NASA’s long history of funding facilities for ground-based planetary research—in contrast to ground-based astrophysics, which has always been NSF’s bailiwick. The list includes a 1.5-meter telescope, which NASA built at Bigelow Observatory north of Tucson, Arizona, to map the near side of the moon for the Apollo program; a 2.7-meter telescope at McDonald Observatory in western Texas, and a 2.2-meter telescope in Mauna Kea, Hawaii. NASA stopped supporting those telescopes years ago. Also in Hawaii, NASA has the 3-meter Infra-Red Telescope Facility (IRTF), holds a share in the 10-meter Kecks, and footed the bill for the smaller Keck outrigger telescopes. From its Solar System exploration budget of $590 million for fiscal year 2002, NASA spent about $8 million on individual grants and facilities for ground-based planetary astronomy, plus $3.5 million on the Spaceguard goal, compared with only around $2 million in grants for planetary astronomy by NSF.

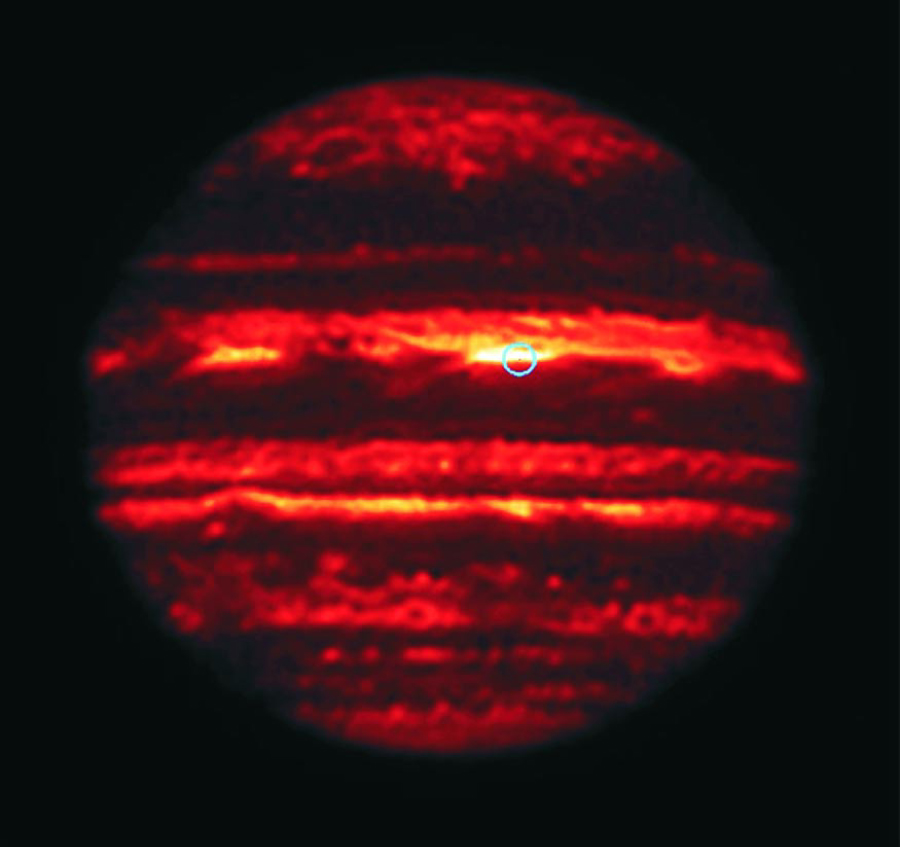

The initial discoveries that inspire space missions, the characterization of specific destinations for planning missions, and a context in which to interpret space results are all provided by ground-based observations, argue planetary astronomers. Take the Kuiper Belt, says Jewitt, who, with Jane Luu in 1992, found the first object in the ring of small bodies orbiting the Sun beyond Neptune. “We can study comets in their nursery before they are kicked into the inner Solar System. But how can you explore the Kuiper Belt if you don’t have a systematic survey of what’s in it? You have to find [the objects] first, measure them, determine their orbits, and then plan missions.” The LSST would do that, he adds. Another example is a probe that NASA sent to Jupiter. “It was a very good thing we had ground-based results,” says the University of Arizona’s Mark Sykes. “They showed that the spacecraft went into the one anomalous hot spot.” By investing a very modest amount in ground-based planetary astronomy, Sykes adds, “NASA leverages a much greater return on far more expensive [space] missions.”

S is for space

As it happens, NASA’s Weiler says he doesn’t plan to reduce support for ground-based planetary astronomy. But he’s not convinced that the LSST should be a NASA project. And he’s none too pleased at being told to take part in it by the Solar System exploration decadal survey. “Their charter was to provide scientific priorities. They went a step beyond that, and tried to give us implementation advice,” says Weiler. If NASA pays for the LSST, he adds, “they’ve also got to tell me which space mission I should cut off to get that money. That’s the kind of advice I’d like to get from advocates of the LSST.” If he were given the money to build the LSST, would he want to? “No,” he says, “I would still say NSF is the appropriate agency. The last time I checked, the S in NASA stood for space.”

Complicating the LSST situation is PanSTARRS, a smaller project whose science goals overlap those of the LSST. PanSTARRS was awarded $40 million last fall from the US Air Force. “If we are interested in using taxpayer dollars wisely, is the LSST the best investment?” asks Weiler. For their part, LSST proponents view PanSTARRS as a warm-up exercise, though some do worry that it could throw a monkey wrench into raising money for the bigger project.

Nor does Weiler dispute that ground-based observations support space missions. But, he says, “I could probably write a proposal justifying any telescope on Earth as supporting NASA missions. I am drawing the line at direct mission support.” That would include, for example, mapping out the orbit of Saturn’s moon Titan or identifying guide stars to help point the Hubble Space Telescope. Historically, NASA needed to do some planetary astronomy for its missions, says Weiler. “But somehow that got translated to general curiosity-based science.”

Weiler points to the so-called Augustine panel, which in 2001 advised the president against moving ground-based astronomy from NSF to NASA (see Physics Today, November 2001, page 27

Fuzzy support

But it is fuzzy for planetary astronomers. “If there is observational work that cannot be justified” as supporting space activities, says Sykes, “I can’t think of anything. It’s not like NASA is foreclosing any part of the Solar System to spacecraft investigation.” The situation, adds Jewitt, “shows a senseless lack of cooperation between NASA and NSF that is working against the best interests of the US in this area of science.”

For the most part, planetary astronomers are not worried about their field’s immediate future. And they’re all pleased by the 3% increase in NASA’s research and analysis budget—which, for planetary astronomy, covers mostly individual grants. “I’m not worried right now,” says Sykes. “But what I am worried about is whether NASA understands the need for doing [ground-based observing as] the necessary homework to get the most out of mission investments.”

As for NSF, Wayne Van Citters, who heads the agency’s astronomy division, says, “If NASA were to decrease funding for planetary astronomy, we would do our best to respond to the increased proposal pressure.” But, Van Citters adds, “I doubt we could respond fully without additional funds, which could take some time to develop.”

Still, for planetary astronomers, the worry about NASA’s bailing out is exacerbated by the nagging fear that “no” is the answer to a key question: Would NSF really pick up the slack?

Potentially hazardous asteroid. Although it won’t come close to hitting Earth for at least 1000 years, that’s the official designation for asteroid 1999 JM8. The asteroid measures 7 kilometers across and was 11 million kilometers from Earth when it was imaged in 1999 with Arecibo’s radar.

LANCE BENNER

Infrared imaging of Jupiter taken from the ground-based InfraRed Telescope Facility in 1995 revealed that NASA’s Galileo probe descended into an atypical hot spot (blue circle), which radiates at 5 microns.

GLENN ORTON, JPL

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org