One man, one hundred meetings, and a physics subfield

DOI: 10.1063/1.3001861

“Joel is remarkable.” “Everybody feels like he is their brother or father.” “He has a magnetic personality.” Comments like those come from everyone who knows Joel Lebowitz. And everyone knows him, or at least everyone remotely involved in statistical mechanics does. As Michael Fisher, a theorist at the University of Maryland, College Park, puts it, “Anyone who knows Joel, and sees him in action, loves him as a person.”

The action that most people have seen is the statistical mechanics meeting that Lebowitz has orchestrated twice a year since 1959. The 100th meeting—but not the last—will take place in December at Rutgers University, where Lebowitz is on the physics and mathematics faculties. “It’s truly astonishing to think that one person has organized 100 meetings,” says Haverford College experimentalist Jerry Gollub. “It’s an amazing service to science.”

“The Yeshiva–Rutgers meetings”—the informal name for the meetings based on where Lebowitz has held them—“have played a huge role in the statistical mechanics community. The field was the Cinderella of physics, and Joel has become a focal point for the field,” says Fisher. “The exact solution of the mean spherical model was announced there. The solution of the Percus–Yevick equation for hard spheres was announced there. In 1971 all the renormalization group ideas—for which Ken Wilson got the Nobel Prize—were presented, and everything exploded,” adds David Chandler, a theoretical chemist at the University of California, Berkeley. “I remember the first time I went, in 1967. There was a guy snoring next to me. Joel said, ‘Professor Onsager, it’s your turn,’ and he gets up and gives a talk. For me it was thrilling—I was a graduate student, and here I was having [Lars] Onsager almost snoring on my shoulder.” Onsager won the Nobel Prize the following year.

Chemistry, math, condensed matter, biophysics, chaos, econophysics, and bioinformatics are among the fields that have been represented at the Yeshiva–Rutgers meetings. “When things are cooking in [statistical mechanics], Joel has the judgment to bring it to the forefront of the stage, and as a result, he has nurtured an awful lot of science,” says Chandler, who a few years ago started a smaller annual conference inspired by Lebowitz’s meetings.

Says Pierre Hohenberg, New York University’s senior vice provost for research, “Theoretical physics is omnivorous and universal and its practitioners do not hesitate to venture into far-flung areas of knowledge. That is in the spirit of these meetings.” And, he adds, the meetings have been key in fostering good communication. “Every field will have its rivalries, and this is a place where one can work things out. Joel has played a role in creating a fruitful scientific environment. It’s quite unique.”

At the conference, a few invited talks last 20–30 minutes, but most people give 5-minute talks “with no visual aids,” says Lebowitz. “I learned that if they had a slide, they’d put up 27 equations. I tell them to think of their talk as an abstract,” and then people can talk more over coffee or cocktails. “The conference is very equalizing,” says Jennifer Chayes, a mathematical physicist who heads Microsoft Research New England. “This is something special about Joel. He views everyone as equals, and that has a wonderful effect on the field. I don’t know of anywhere else where it would work for both famous professors and grad students to give these short talks.”

The meetings, originally one-day affairs, were inspired by a meeting in general relativity at his then home campus, the Stevens Institute of Technology, Lebowitz says. Now they last three days, and in recent years Lebowitz has added celebrations of significant birthdays. The meetings are intended, he says, “to foster openness and collegiality, to bring in younger people, minority people, to give younger people a chance to present their work when senior people are listening. I want to keep a fraternal, informal spirit in the community.”

Every meeting features a session on human rights. At December’s meeting Alan Beyerchen, an Ohio State University science historian and author of Scientists Under Hitler: Politics and the Physics Community in the Third Reich (Yale University Press, 1977), will talk. Many meeting attendees attribute Lebowitz’s commitment to human rights to his own imprisonment in Auschwitz during World War II. “Joel gives everyone the impression that you need to be a good citizen, not just a good scientist,” Chayes says.

For the upcoming 100th meeting, Lebowitz’s friends have taken over a banquet night. Says Princeton University’s Michael Aizenman, “We want to celebrate both the jubilee of these remarkable meetings and the exceptional person who established them.”

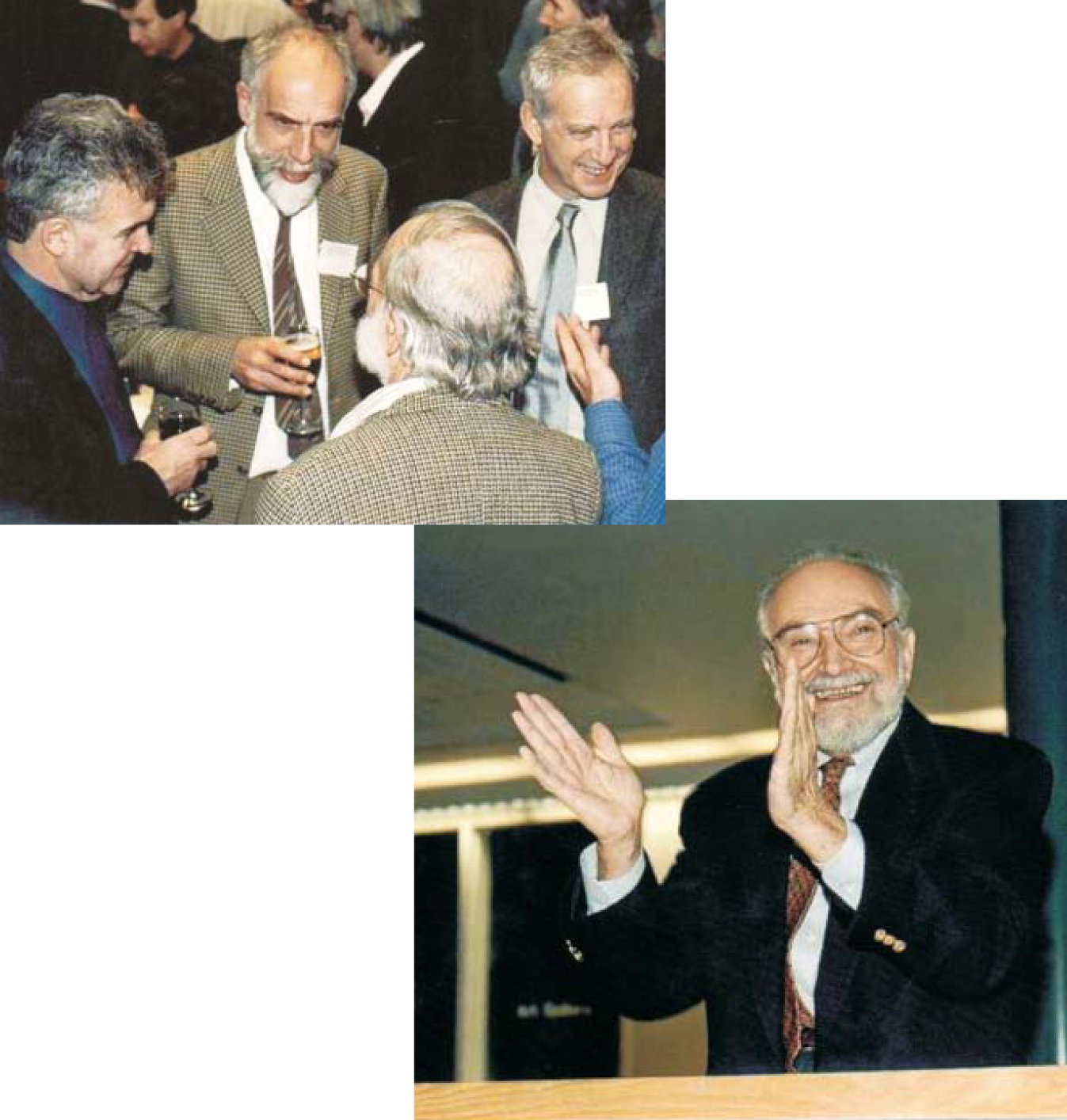

Joel Lebowitz at the December 2003 statistical mechanics meeting (below), which honored Freeman Dyson on his 80th birthday. At the same meeting (from left) Gene Stanley (Boston University), Jürg Fröhlich (ETH Zürich), Édouard Brézin (École Normale Supérieure, Paris), and, with his back to the camera, Michael Fisher (University of Maryland, College Park) chat over cocktails.

JEFF MOZZOCHI (C.J.)

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org