Mercury Telescope Spins Up

DOI: 10.1063/1.1634524

“Liquid mirrors have one single advantage. Only one. It’s cost,” says Ermanno Borra of Laval University in Quebec, Canada. In the early 1980s, Borra resurrected the idea of liquid mirror telescopes, first put forth in 1850 by the Italian astronomer Ernesto Capocci. The disadvantage is that they can’t be tilted, he says. “You are stuck with the strip of sky above you. But it’s not as bad as it sounds.”

Liquid mirror telescopes are suited to surveying classes of objects and to studying supernovae and other variable phenomena. “Look at Paul [Hickson],” says Borra. “He has a 6-meter telescope to do cosmology. With a conventional glass mirror, you can cover the whole sky, but you have to share with a lot of people. Cost, cost, cost. That’s what it’s all about.”

Hickson, an astronomer at the University of British Columbia, Canada, spearheaded the Large Zenith Telescope, the newest and biggest liquid mirror telescope. It is located about 60 kilometers east of Vancouver and partners come from Laval University, the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, SUNY Stony Brook, and Columbia University. The LZT cost about $500 000, says Hickson. “If you include the parts we borrowed, it would be about $1 million.” That’s more than an order of magnitude less than what a glass mirror telescope of similar size would cost.

Liquid assets

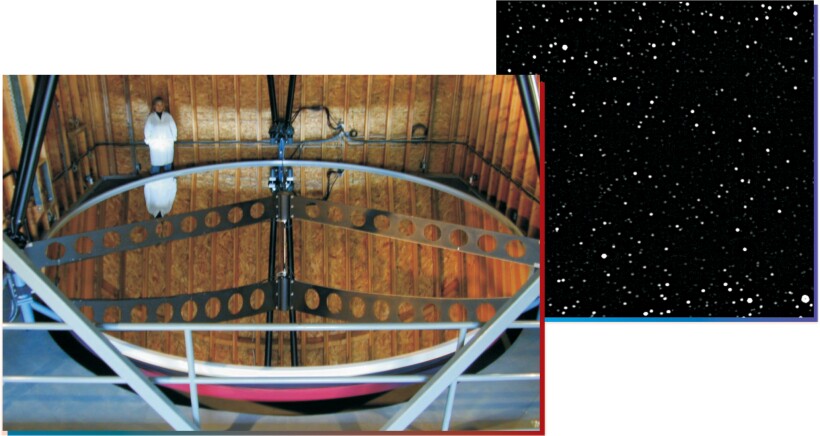

The cost difference lies largely in the ease of spinning a liquid into a smooth parabola compared with the difficulty of grinding and polishing glass to an accuracy of tens of nanometers. The LZT’s primary mirror consists of mercury spun to form a coating on a fiberglass and foam base. The mirror is supported by an air bearing and rotated magnetically. At the focus are corrective lenses and a detector whose positions can be minutely adjusted via six support legs. The focal length depends solely on gravity and the rate of rotation: It is 9 meters with a mirror period of 8.5115 seconds. Atmospheric seeing limits the resolution to about 1 arcsecond, and the telescope is sensitive in the mostly visible range of 0.3–1 micron.

It takes about 150 liters of mercury to get a continuous 5-millimeter-thick layer. Once the layer is stable, mercury is drained from the center; the thinner the final layer, the less the image is distorted by waves from the spinning. So far, Hickson has reached 2 mm; by fine-tuning the shape of the dish, he’s hoping to dip below 1 mm.

The mercury comes gratis from industries that are switching to less toxic materials. At the LZT, respirators are worn as needed—usually during the first 10 or so hours after spinning up the telescope, says Hickson. By then, a transparent oxide layer forms and seals the surface, and the level of mercury vapor, which can harm the brain and nervous system, plummets.

Proof pending

The LZT was built on the shoulders of, most notably, a 2.7-meter mercury telescope that Hickson made in his backyard. Other liquid mirror projects include 2.7-meter telescopes in Alaska and Ontario that physicists use to study the atmosphere with LIDAR (light detection and ranging) and a 3-meter New Mexico-based NASA telescope that, until last year, kept its eye on space junk. Borra, together with colleagues in Belgium, is working on an array of 4-meter liquid mirror telescopes.

Hickson “built the [LZT] almost single handedly. It’s amazing what he’s done,” says Stony Brook’s Kenneth Lanzetta. Along with Columbia, Stony Brook is contributing cash to the LZT and sees it as a stepping stone to a much bigger project, the Large-Aperture Mirror Array (LAMA). “We are interested in making sure that the telescope can deliver what it needs to convince people to fund the next step,” Lanzetta says. “We need to get some solid scientific results,” adds Hickson.

Still in the early planning phase, LAMA is foreseen as a close-packed array of liquid mirror telescopes with an effective aperture of 50 meters. The LAMA team estimates the array could be built within the decade for $50–100 million. Using corrective optics, LAMA could be steered by up to 4 degrees and track objects for up to 30 minutes. The tracking capability opens the door to correcting for atmospheric turbulence by adding adaptive optics to a secondary mirror. “We will pick fields that have one or more suitable reference stars,” says Hickson. Unlike most interferometers, which measure interference fringes, LAMA would use Fizeau interferometry, in which light from the constituent telescopes is combined to directly form a high-resolution image.

After attending a presentation on LAMA in September, Philippe Dierickx, project engineer for Europe’s Overwhelmingly Large Telescope, summed up astronomers’ attitudes about liquid mirror telescopes as “rather positive, with a very important reservation: This concept is very specific to certain scientific goals. The perception is that it can do targeted science for extremely low cost. It could fill a gap before a flexible ELT [extremely large telescope] comes into focus.”

Shooting for the moon

Meanwhile, progress on liquid mirror telescopes has propelled Roger Angel to propose putting a 20-meter one on the Moon. From the lunar South Pole, the University of Arizona astronomer says, “there is absolutely unique science you could do with a deep survey.” Such a site could be powered by the Sun, he says, and nearby craters that appear to contain water could be studied. Mercury would freeze on the Moon, but an organic liquid with an added reflective coating might work.

In the wake of the Columbia shuttle disaster, Angel says, “everyone is asking, ‘What do we use astronauts for?’ Mars is intrinsically interesting, but going to the Moon as an intermediate step is a heck of a good idea. I think the Moon and liquid mirrors were made for each other.”

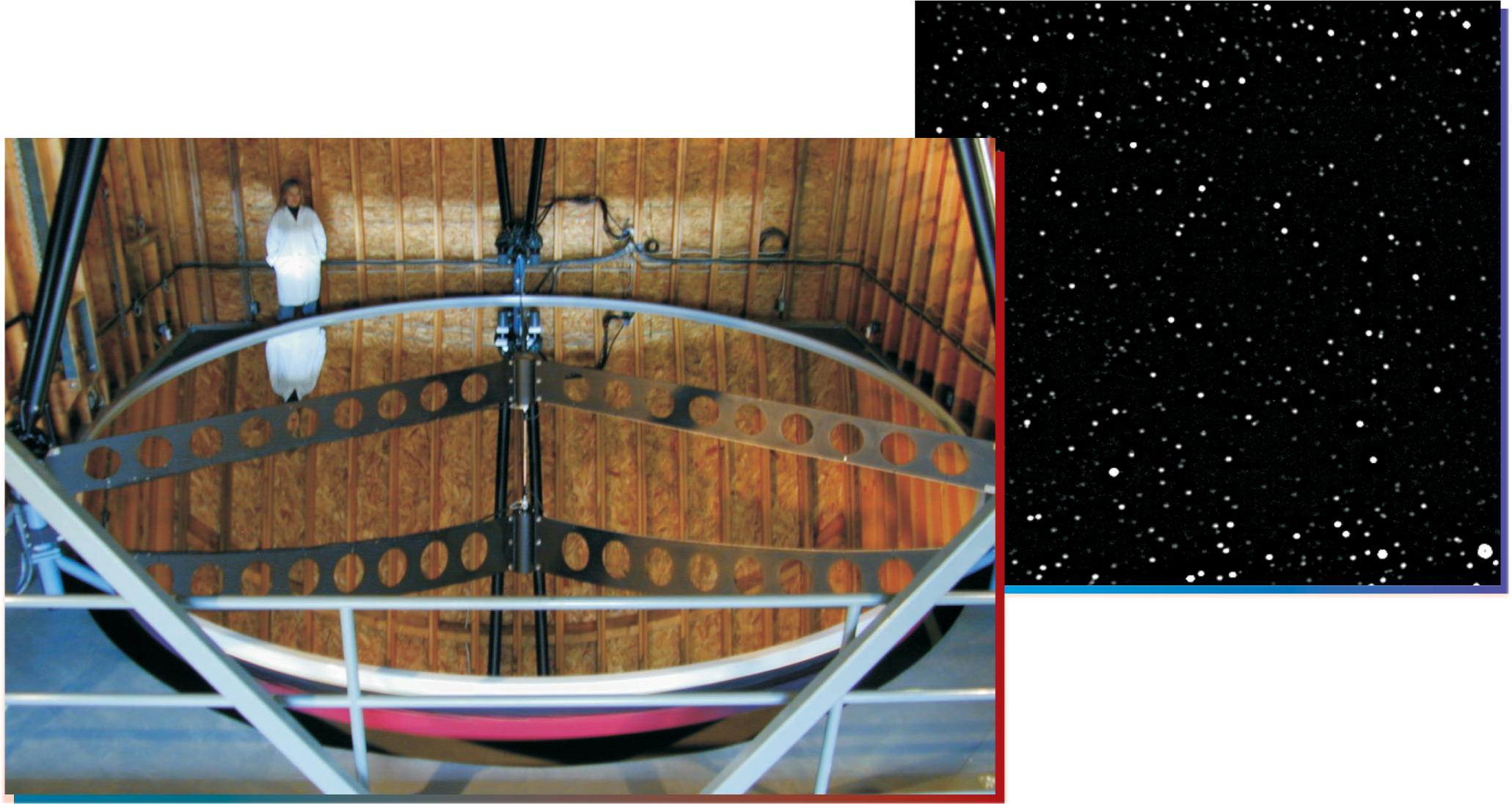

The 6-meter spinning mercury telescope outside Vancouver, British Columbia, is the largest of its breed. The star field (above), an early image collected by the telescope, is a 100-second exposure, one-quarter degree square in size.

PAUL HICKSON

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org