Magnetic field induces spatially varying superconductivity

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.5034

In 1957 the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory emerged as the first quantum mechanical model of what would become known as conventional superconductors. Below a critical temperature, the highest-energy electrons in those materials form pairs with antiparallel spins. Pairing up allows the electrons to act like bosons rather than fermions and condense into a collective state that moves without resistance. (See the article by Howard Hart Jr and Roland Schmitt, Physics Today, February 1964, page 31

But other models for superconductivity exist. In 1964, for example, Peter Fulde and Richard Ferrell and, independently, Anatoly Larkin and Yuri Ovchinnikov predicted that a large magnetic field could induce a different type of superconducting state. 1 Known as Fulde-Ferrell-Larkin-Ovchinnikov (FFLO) superconductivity, the state’s parameters would vary periodically in space, unlike the homogeneous BCS state.

Direct evidence of FFLO superconductivity has long been elusive, however, in large part because the predicted state is unstable. A few materials, such as quasi-two-dimensional organics and the heavy-fermion system cerium cobalt indium-5, have shown some signatures of a potential FFLO state. Now Kenji Ishida of Kyoto University in Japan, his graduate student Katsuki Kinjo, and their colleagues have found the most direct evidence to date of the state.

2

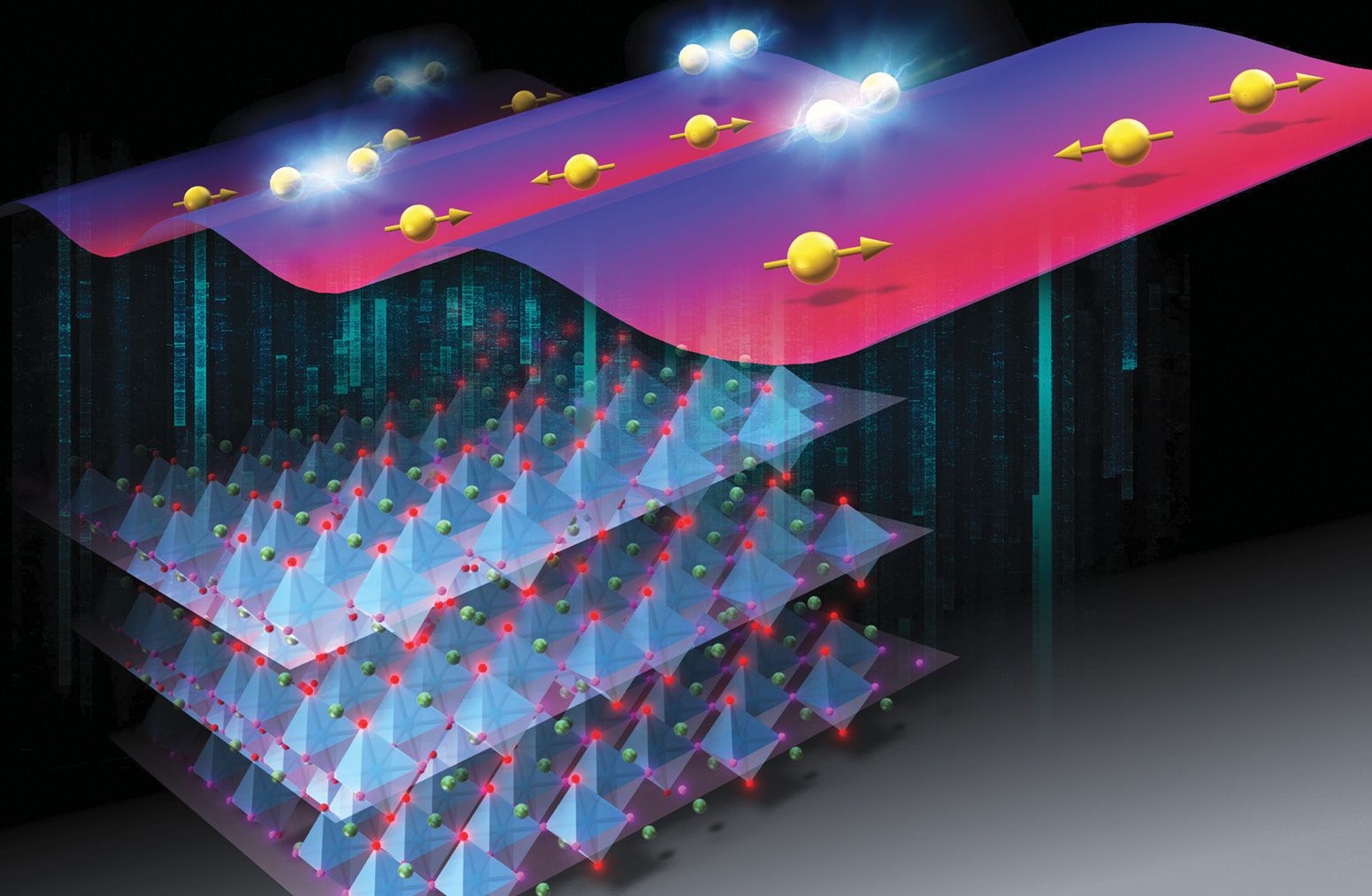

Their observation of modulations in strontium ruthenate’s spin density, illustrated in figure

Figure 1.

Strontium ruthenate, illustrated in the bottom left, becomes superconducting at temperatures less than 1.5 K. The nature of that behavior has been the subject of excitement and debate since the mid 1990s. New results add another theory to the mix: an unusual and hard-to-find form of superconductivity whose order parameter varies spatially under the influence of sufficiently strong magnetic fields. Those variations, depicted by the sinusoidal surface at the top, take the form of regions of superconducting electron pairs and regions of high spin density that result from unpaired electrons. (Courtesy of Kenji Ishida.)

Gaining momentum

The key difference between BCS and FFLO superconductivity is the response to magnetic fields. In the case of BCS, an applied magnetic field, if strong enough, twists the spins apart and destroys the material’s superconductivity—a phenomenon known as Pauli pair breaking. An FFLO superconductor also eventually succumbs to pair breaking under the influence of a sufficiently strong field. But when subjected to slightly weaker fields, the FFLO gains its signature inhomogeneity.

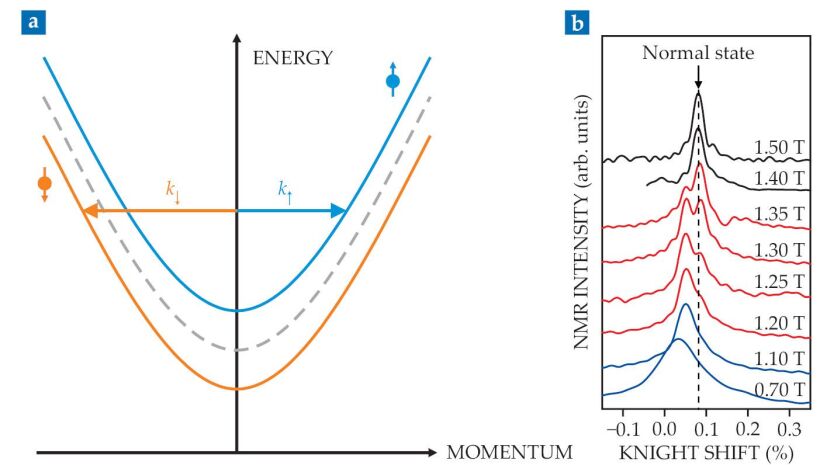

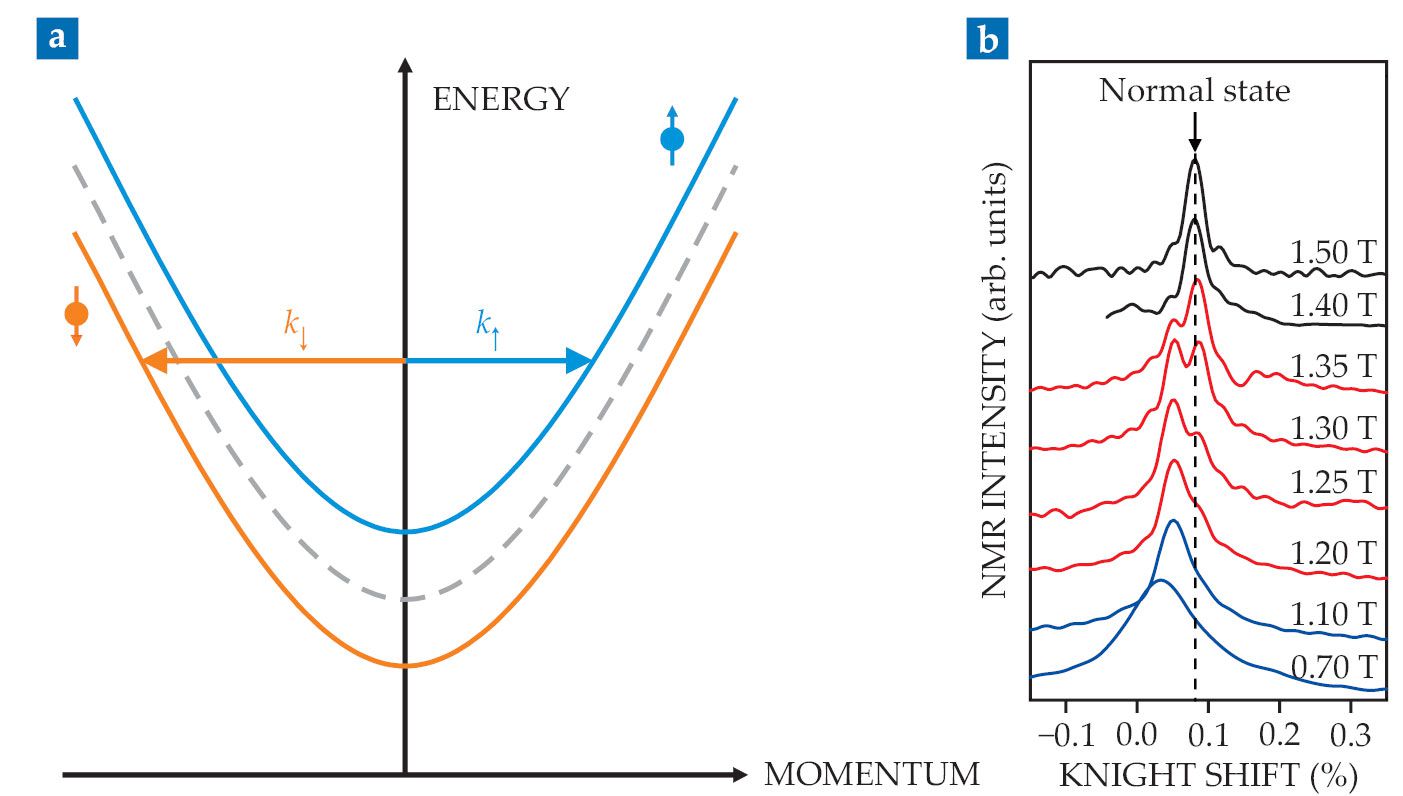

To understand how, consider the simple band structure depicted in figure

Figure 2.

FFLO superconductivity arises from Zeeman splitting. (a) In the absence of a magnetic field, spin-up and spin-down electrons have the same energies and momenta (gray dashed curve), so when the highest-energy electrons pair up in the superconducting state, the net momentum is zero. But in the presence of a magnetic field, spin-up (blue) and spin-down (orange) electrons take on distinct momenta k. When the highest-energy electrons pair to form an FFLO state, the pairs have nonzero net momentum and create spatial modulations in the spin density. (b) For strontium ruthenate at 70 mK, NMR measurements—given in terms of the Knight shift, which quantifies the NMR frequency shift—show the transition with increasing magnetic field from homogeneous superconductor (blue) to FFLO superconductor (red), characterized by double peaks, to nonsuperconducting (black). (Adapted from ref.

Many superconductors, including most elemental ones, are well-described by BCS theory; finding materials suitable for an FFLO state has been a challenge. For starters, unlike robust conventional superconductivity, even dilute defects in the sample prevent the state’s formation. So a candidate material must be quite pure and nearly perfectly crystalline. Its carriers must also undergo strong Zeeman splitting. Finally, the FFLO state requires high magnetic fields—higher fields than those at which superconductivity disappears in most materials as a result of induced vortex currents. So a suitable material must have Pauli pair breaking, rather than vortex formation, as the limiting factor on superconductivity.

Strontium ruthenate—Sr2RuO4 or SRO—is, in many respects, a promising candidate for FFLO superconductivity: It can be fabricated with few defects and possesses charge carriers with large effective mass, which produces large Zeeman splitting. Its layered structure, shown in the bottom left of figure

For many years, however, SRO was thought to be a spin-triplet superconductor, which has electron pairs with parallel spins. In 1998 Ishida’s group was the first to produce NMR data that seemed to confirm that supposition. Spin-triplet superconducting pairs would be manipulable with magnetic fields, which makes them promising for spintronics and quantum computing. But they can’t form an FFLO state. Zeeman splitting would have no effect on the net momentum of spin pairs pointing in the same direction.

After two decades of experiments in support of the spin-triplet interpretation, studies in 2019 and 2021 by Stuart Brown of UCLA and his colleagues reported NMR results that contradicted that picture.

3

(See Physics Today, September 2021, page 14

Seeing double

Ishida and his colleagues first replicated Brown’s results. 4 They then used the same technique to examine SRO close to the critical magnetic field, above which the material returns to its normal state. The low-energy NMR pulses may prevent heating, but they also make the signal weak. So each spectrum took an order of magnitude longer than a typical NMR measurement. The researchers tested a range of temperatures from 70 mK to 1.6 K and magnetic fields up to 1.5 T.

The NMR spectra are given in terms of the Knight shift, which quantifies the NMR frequency shift. They indicate the electron-spin susceptibility in the vicinity of the probed nuclei, in this case oxygen-17. In its normal state, SRO has a certain, uniform spin susceptibility, with electrons and their accompanying spins spread out evenly. That state produces one NMR peak, as shown in black in figure

Just below the critical field of 1.4 T, a second NMR peak appears, shown in the red spectra in figure

Kinjo, Ishida, and their colleagues constructed a full phase diagram for the homogeneous and the FFLO superconducting phases, with the FFLO occupying the high magnetic field, low-temperature region. The magnetic fields in their study were about a tenth of those necessary for previous FFLO candidates, which makes SRO a practical choice for future FFLO investigations.

Although encouraging, the new result isn’t conclusive. The only definitive evidence would be an observation of spatial modulations in the superconducting order parameter through, for example, measurements of the superconducting gap—the small energy gap that opens when electrons pair up. That smoking gun could come in the future from scanning tunneling microscopy measurements.

References

1. P. Fulde, R. A. Ferrell, Phys. Rev. 135, A550 (1964); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.135.A550

A. I. Larkin, Y. N. Ovchinnikov, Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 47, 1136 (1964).2. K. Kinjo et al., Science 376, 397 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb0332

3. A. Pustogow et al., Nature 574, 72 (2019); https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1596-2

A. Chronister et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2025313118 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.20253131184. K. Ishida et al., J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 89, 034712 (2020). https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSJ.89.034712