Lowering Earth’s temperature with a dust shield

The Sun illuminates Earth’s atmosphere in this photo taken last year from the International Space Station.

NASA

Purposefully manipulating Earth’s climate by managing the amount of solar radiation that reaches the atmosphere has the potential to lower global temperatures, but the approach is controversial. Geoengineering doesn’t address the root cause of the problem—copious emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases—and it brings up moral questions. Why should we reduce our use of fossil fuels if we can burn them and keep Earth at our preferred climate equilibrium? And given that some changes to the climate may benefit certain regions, who should decide whether to use geoengineering tools and to what extent? (See, for example, Physics Today, June 2021, page 22

Geoengineering approaches that add aerosols into the atmosphere to better reflect sunlight could also bring unintended consequences to weather patterns and the environment. To lower temperatures without modifying Earth’s atmosphere, some researchers have studied space-based geoengineering, which would put large mirrors into orbit or use swarms of small satellites or dust clouds from asteroids to shade the planet.

Benjamin Bromley

Adapted from B. C. Bromley, S. H. Khan, S. J. Kenyon, PLOS Clim. 2, e0000133 (2023)

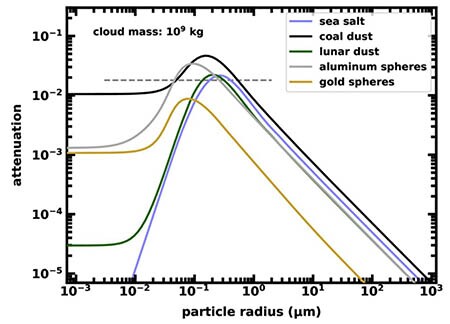

The amount of shade that a dust cloud offers depends on the individual particles’ cross-sectional area, absorption properties, and light-scattering efficiency. The graph shows how attenuation of sunlight by a particle cloud varies with the particles’ size and, more weakly, their density. (Of the dust types in the figure, coal dust is the least dense, and both lunar dust and aluminum spheres are the densest.)

In their simulations, the researchers considered a cloud of equally spaced dust particles at the Earth–Sun L1 Lagrange point. That spot is 1.5 million km from Earth and has an uninterrupted view of the Sun. Dust grains located at L1 can remain there for only hours to days before they’re moved elsewhere because of the enhanced gravitational forces of attraction and repulsion from the Earth–Sun system. To see meaningful temperature reductions on Earth, a dust cloud would need to stay at the L1 point for at least a few days.

Bromley and his colleagues show that such a target could be reached, and the most promising approach based on their calculations would be to seasonally launch dust clouds toward L1 from the lunar surface. Not only does the Moon have optimal-sized grains for shading Earth, but it also has a lower escape velocity than Earth so less energy would be required to launch dust grains from its surface. In fact, the calculations suggest that a solar-panel array with an area of a few square kilometers could do the job. (B. C. Bromley, S. H. Khan, S. J. Kenyon, PLOS Clim. 2, e0000133, 2023

More about the authors

Alex Lopatka, alopatka@aip.org