Levitating beads reveal radioactivity

DOI: 10.1063/pt.uehq.hnej

The beads under study by David Moore’s group at Yale University barely move as they hover inside a vacuum chamber. A focused laser confines the 3-micron-wide silica spheres and cools them to minimize thermal jitters. Yet every now and then, the beads jolt 10 or so nanometers. The cause of each abrupt kick: the recoil of a nucleus in the bead that underwent radioactive decay. The new demonstration offers a blueprint for measuring radioactivity without the need to detect often-elusive decay products.

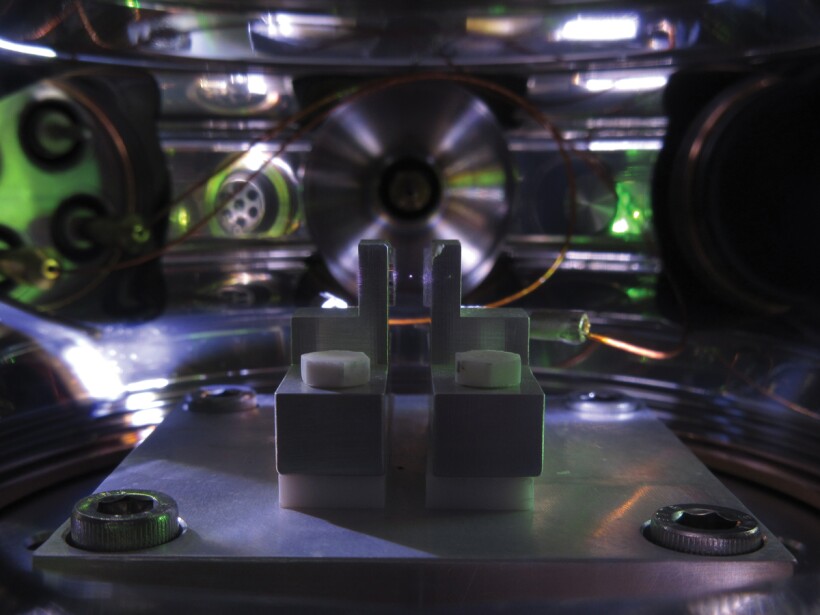

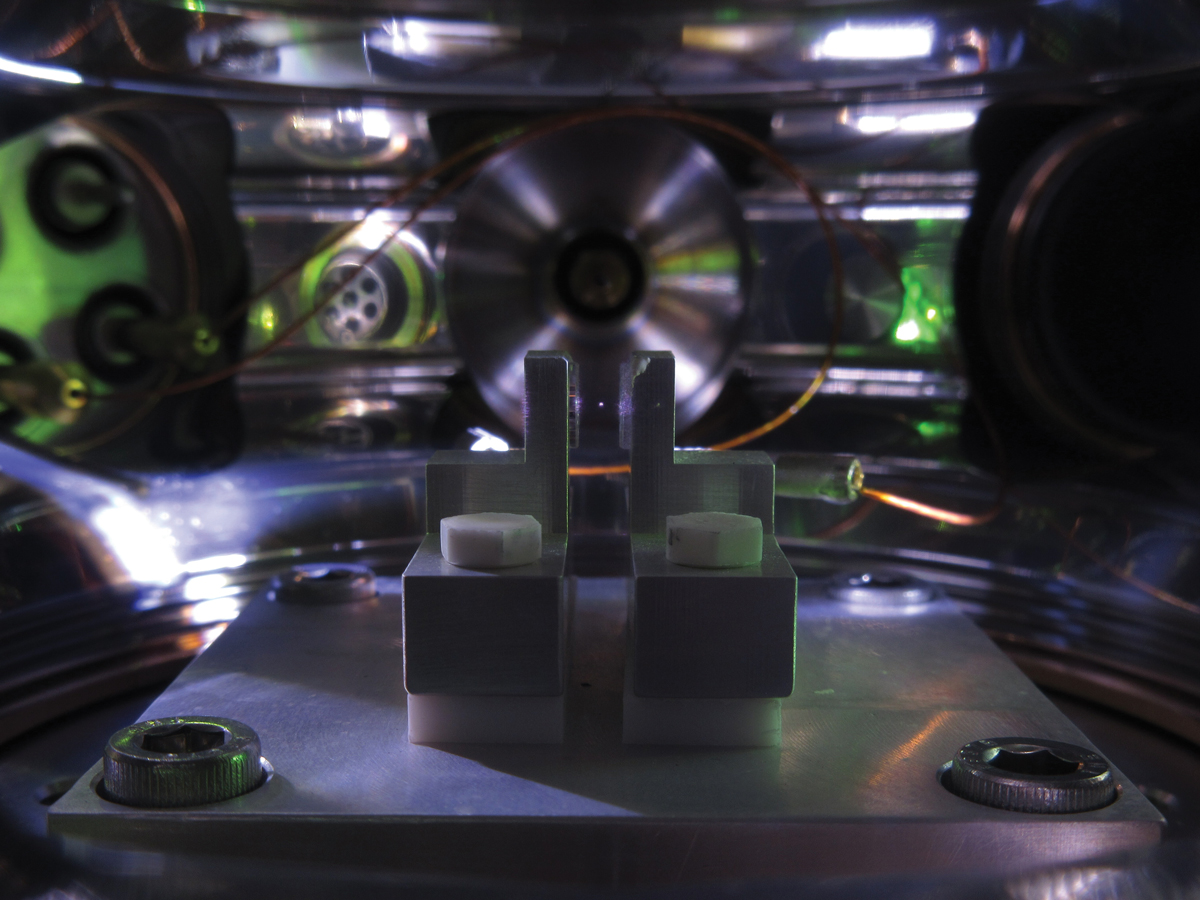

A small silica sphere hovers nearly motionless in a vacuum chamber. Credit: Yale Wright Lab

The technique works by measuring the momentum of a radioactive nucleus that recoils in one direction upon emitting a particle in the other. The researchers embedded solid beads with radioactive lead nuclei and loaded individual beads into the optical trap. Observing each bead continuously for up to three days, Moore and colleagues recorded a series of sudden jumps. The events could be explained by nuclei that emitted alpha particles, recoiled, and then transferred their momenta after crashing into neighboring atoms in the bead. By also tracking the overall charge of each bead, the researchers were able to confirm that changes in charge accompanied those in position.

The technique should work for all types of radioactive decays: Nuclei recoil regardless of whether their emissions include alpha particles, which are generally easy to measure via traditional detectors, or neutrinos, which are not. That thoroughness could prove valuable for researchers probing fundamental physics or investigating the precise compositions of nuclear materials. But first, they will have to improve the technique’s sensitivity to enable the detection of lower-energy radioactive processes, such as beta emission and some hypothesized rare decays. Moore’s group plans to spot the recoils associated with those processes by using smaller, less-massive spheres. (J. Wang et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 023602 (2024)

The article was originally published online on 30 May 2024.

More about the authors

Andrew Grant, agrant@aip.org