LANL Rescues Cosmic-Ray Detector

DOI: 10.1063/1.1506745

Gus Sinnis was pleasantly surprised when he and his colleagues got the High Resolution Fly’s Eye purring this past May. They’d never touched the ultrahigh-energy cosmic-ray detector before, and it had been collecting dust for nearly eight months ever since heightened security after last September’s terrorist attacks stopped the experiment dead in its tracks.

The new security measures banished the university scientists who run HiRes from their experiment, which sits on two hills on the US Army Dugway Proving Ground in western Utah. The site is for testing equipment to protect US forces against biological and chemical attacks. Ironically, one reason scientists chose to build HiRes and its predecessors at Dugway was because the army base offered protection against vandalism.

With binocular vision from two arrays of mirrors separated by about 12 km, HiRes scours the atmosphere for fluorescence flashes caused by impinging cosmic rays with energies of 1017 eV and higher. “Somehow nature is accelerating subatomic particles to macroscopic energies. It’s a mystery what the mechanisms are,” says HiRes spokesman Pierre Sokolsky, a physicist at the University of Utah. “We’d just got both of our sites fully operational at the beginning of 2000, and then—bam!—we were kicked off. So this was particularly frustrating. To do the physics we want to do, we need three to five years of running.” (See the article by Sokolsky and colleagues in Physics Today, January 1998, page 31

The deal that got HiRes back on the air was brokered by Gene Loh, a member of the HiRes collaboration. Currently an NSF program officer for Milagro, a cosmic gamma-ray detector at Los Alamos National Laboratory, Loh wondered if the Milagro scientists, with their LANL security clearance, might be allowed onto the HiRes site. Dugway said yes, and Milagro project scientist Sinnis and about a dozen other LANL scientists, engineers, and technicians volunteered their help.

In practice, helping HiRes means sending four people a night during the two darkest weeks of the month. “The first night, I was on the phone almost the whole night,” says Sinnis. “After that, it was once or twice a night, and then not much. It was relatively painless.”

But LANL scientists don’t come cheap. Each two-week shift costs about $75 000. “NSF had sticker shock at what it cost for us to operate,” says Sinnis. At press time, LANL scientists were completing a second shift, and the HiRes collaboration was trying to rustle up money for the coming months.

“We are very grateful to LANL,” says Sokolsky. “We are very happy that they have volunteered to help, and that they would take our plight so seriously.” But for the longer term, he says, the HiRes team is seeking other solutions, including obtaining security clearance for some of its members, converting HiRes to remote operability, and moving. “As a university group, this doesn’t work. We must have research opportunities for non-US citizens. Half of our professors, and a larger fraction of our grad students, are not US citizens.”

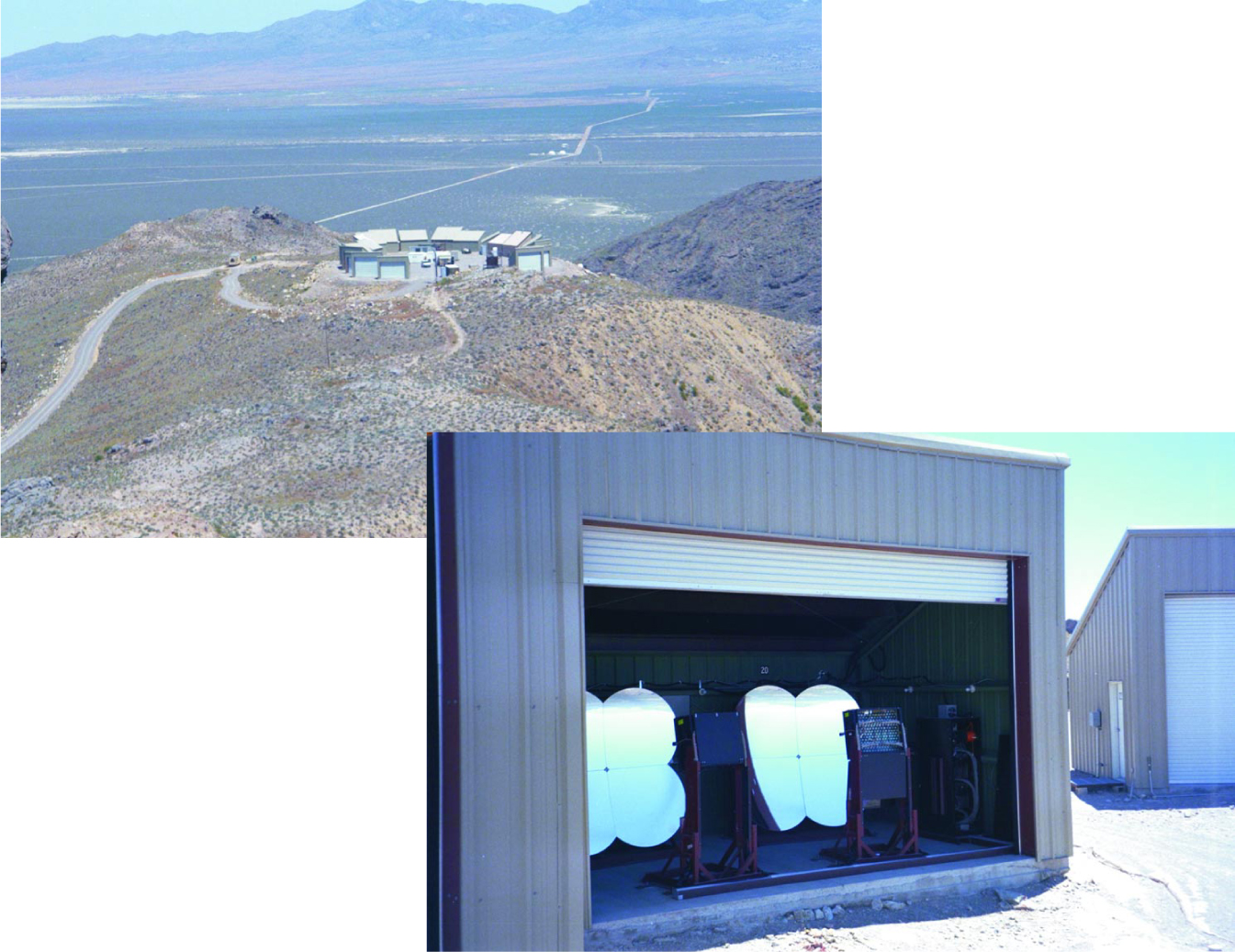

Hires monitors the sky for fluorescence flashes due to ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays. Together, two groups of mirrors, housed in sheds (bottom) arranged in circles (top), give the experiment binocular vision.

LAWRENCE WIENCKE

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org