Juggling dual-country careers: The interviews

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.2424

The challenge of working in more than one country was the topic of a story

- Katherine Brown, biophysicist

- Reinhard Genzel, astronomer

- Morten Hjorth-Jensen, nuclear physicist

- Hitoshi Murayama, particle physicist

- Lidia Smentek, condensed-matter physicist

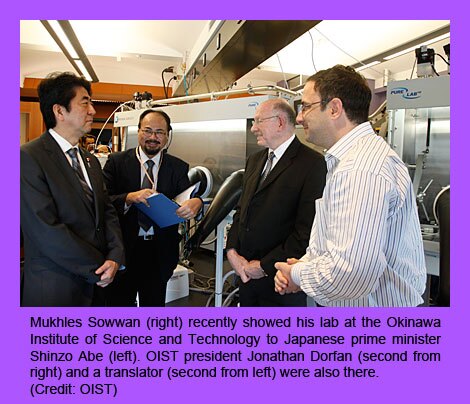

- Mukhles Sowwan, nanoparticle physicist

Katherine Brown is a biophysicist who has been commuting between the UK and the US for about eight years. She first split her time between Imperial College London and the University of Texas at Austin; her UK base is now the University of Cambridge. Her research is in military medicine, on blast-related injuries and biodefense vaccines and diagnostics. Family reasons are what pushed her to opt for this more taxing, split life, but it ‘would not be possible without Skype,’ she says.

PT: Why did you switch from working full-time in the UK to going back and forth between the University of Texas at Austin, and Imperial College London, and more recently between UT and the University of Cambridge?

BROWN: My history for doing this is completely personal. I started to work remotely [at my UK job] to help my father, who was in the US, when he was diagnosed with cancer. Then I discovered I was pregnant and decided it was going to be way too much, having an ill father and a new baby and a husband based in the US. So this precipitated a move to go part time with my position in the UK and to try to come up with a part time position in Austin.

I am now in the physics department at the University of Cambridge developing projects in blast-injury research.

I have worked for nearly 20 years in the UK system. It’s in my interest to keep retaining a post in the UK, partly because I already have an established research reputation there and for my pension.

PT: How do you split your time?

BROWN: It works out to a little more than five months a year in the UK and in the US, closer to seven. The arrangement is flexible, and in reality, I work for both jobs every day. I split my time in a way that is aligned with the working hours of both countries.

PT: What are the benefits of the arrangement?

BROWN: One of the great advantages if you are directly involved in two institutions is that you have a much broader outlook about what is happening both in European and US research. I have found that to be incredibly beneficial for my research at both institutions.

There is one advantage that is kind of personal, but also professional. In the UK, I am on my own most of the time, and that allows me to work much extended hours. It’s this time I use to write grant applications, work on papers . . . And since it happens quite periodically, then when I am in the US I feel I can spend more time with my family knowing I will have these blocks of time to get caught up on writing when I am in the UK. I am not teaching right now, so I have considerable flexibility in terms of travel.

PT: What are the professional disadvantages of straddling two countries?

BROWN: One is that at the moment I live off soft money, and that is not as pleasant as it was when I didn’t live off soft money.

Also, sometimes, because you are not there full time, you end up being a little bit on the fringes of some of the political sides of the department and the decision-making processes. And it takes more work to actually deal with problems. Fortunately, though, I tend to be fairly organized, and my projects always involve collaborations, so usually there is someone [on site] who I can work with to address things in my absence.

PT: What about personal disadvantages?

BROWN: The obvious one is separation from my family and living some of my life by Skype. The routine is that I see [my 4-year-old daughter] for breakfast and when she gets home from school. When she was still in a high chair, I would say, ‘Now take another bite.’ It wasn’t always clear how virtual versus real I was. She might drop her spoon and say, ‘Mama, can you get the spoon?’ When I would say, ‘No, not today,’ she would say, ‘Oh, that’s right. You are in the computer today,’ and scream, ‘Dada!’

Also, the travel can be taxing physically. The other strange thing is that each time I go from one country to the other, I feel I have to restart my life again just a bit—remind my friends I am back in town, get back into a rhythm with my family when I am in the US.

PT: Would you prefer to be in one place?

BROWN: Ultimately, yes. But the question is, Which place? Both places are incredibly stimulating right now. In the UK, I am setting up an entirely new research project for blast studies. And here [in Austin] we are setting up new projects, particularly with industry, and also trying to set up another laser-based system to understand the effects of high-intensity compression waves on cells and tissues. The most powerful laser in the world—the Texas Petawatt Laser—is based in the physics department at UT Austin. That is exciting. From a career point of view, both places offer exciting research opportunities.

PT: Any last comments?

BROWN: I am adapting my career because of changing needs of my family. What I have tried to do is not lose my career. In some ways I am working harder now than I ever have before. It’s impossible to become deadwood. But at the same time, that’s also quite stimulating. You simply can’t coast when you are doing something like this.

For 14 years, astrophysicist Reinhard Genzel has spent several months a year at the University of California, Berkeley, on top of his job as a director at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics near Munich. ‘I am delighted it has worked out,’ he says. ‘Most people thought I was crazy and predicted I would get a heart attack within a year.’

PT: Describe the arrangement you have with your two institutions, the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and the University of California, Berkeley, and why you choose to go back and forth.

GENZEL: I was in Berkeley full time in the 1980s, so there was some personal nostalgia. In the late 1990s [back in Germany], Europe was beginning to look stale. By 1996 or 1997, I was considering going back to the US—it looked like a more exciting research environment. Charlie Townes had been asking from time to time if I wanted to come back. At that time I said, What about a joint appointment?

The main reason I considered this appointment was that we had a joint program building an instrument for SOFIA [the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy]. In the meantime, we have been heavily involved in building one of the instruments for Herschel [Space Observatory].

I have a 100% appointment in Germany and a 25% appointment here [in the US]. So I normalize my life accordingly. My first-order plan was to come to Berkeley during times in Europe that are almost dead—summer and January—so that my absence is not noticed. I do count the days, I feel obliged to.

You have to be disciplined. You have to say no to a lot of things. That doesn’t make you popular. And your colleagues might be slightly envious or feel you are not doing your work—say, if you can’t make it to a committee meeting. I don’t like to do videoconferences all the time.

PT: What are the advantages of working in both places?

GENZEL: First and foremost, I really enjoy the research environment and the different aspects of the research environments in the US and Europe. The culture of how you do science is different. And I love Berkeley. By having this fresh air every half year, I feel I function better as a scientist. The students here [in Berkeley] are great, the postdocs too.

But there is a huge contrast in [financial] support. It’s a paradise in Munich, compared with the struggles here [in the US]. In my case, it’s owing to the stability of the German system that this works—and the fact that the people over there are willing to accept it.

PT: What are the difficulties or disadvantages?

GENZEL: It’s trivialities that can put up a roadblock. For example, the Max Planck Society was interested in setting up an international exchange with Berkeley. As part of this, they rented a house in the Berkeley hills. When I am here, I rent it, but I don’t have to pay for the rest of the year. This has worked well. But auditors said the Max Planck Society should consider ending this. If that happened, I would end my 25% appointment in Berkeley.

Another problem has been the INS [US Immigration and Naturalization Service, now the US Citizen and Immigration Services]. My wife comes with me from time to time. We have green cards. But over the years, I have been noticing an ever increasing spiral of torture. We used to get a smile. Now when we show our green cards, they say, ‘Why have you been out of the country? Why are you not becoming a citizen?’ These are minor trivialities, but they can hang you up.

Morten Hjorth-Jensen is a theoretical nuclear physicist at the University of Oslo in Norway. He is in his second year of splitting his time between there and Michigan State University, where construction of the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams is getting under way. Last year, during his first semester in the US, he missed his wife and wondered, ‘What have I done?’

PT: Why did you decide to spend half of each year in the US?

HJORTH-JENSEN: Norway is a small country, and you have to focus on fewer activities. Nuclear physics is a very small field in Norway. So MSU [Michigan State University] was a fantastic opportunity. It’s the number one school in nuclear physics in the US and most likely in the world. I have always worked closely together with experimentalists, so this is something which has evolved over time. When people at MSU were interested in some kind of split-position arrangement, I wanted to give it a try. The present position at MSU is a three-year rolling tenure position.

PT: How do you split your time?

HJORTH-JENSEN: I teach courses in Norway [at the University of Olso] in the fall, and at MSU in the spring. With good videoconference possibilities, it is easy to stay in touch with students and colleagues at both places. This spring semester, in addition to teaching at MSU, I teach also, remotely, a course in Norway.

PT: What are the upsides of the arrangement?

HJORTH-JENSEN: When you come to a lab with something like 36, 37 dedicated people, experimentalists and theorists alike, who push in the same direction, you can make plans for the future. You can spell out, What are the pressing questions for the field? How can we improve our educational set up? What kind of experiments should we run? What kind of theory is needed?

And they are building up the new FRIB [the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams]. There is a bright future for nuclear physics at MSU. To be a part of this is a unique opportunity.

When you come from a place where I was just together with one or two or three colleagues, and we don’t overlap much, you don’t get the fantastic feeling of being in a larger environment. MSU attracts good students, and you have this big challenge of being surrounded by so much talent. You have to revise every day the way you perceive things.

Also, I must say that my colleagues at MSU took great care of me: [The first year] I was invited almost every weekend to some place. That was cute.

PT: What are the downsides?

HJORTH-JENSEN: The only dislike I have is the family situation, which is tough. The main difficulty is that we [my wife and I] have been living together for 26 years, and there are so many things you take for granted. For this second year, I am trying to reduce the family impact by having periods of five or six weeks in the US and then one week back in Norway.

PT: Anything else?

HJORTH-JENSEN: One thing I hope to establish in the longer term is a student exchange program, so it will be easier for students from Norway to spend time at MSU and vice versa. The exchange would be point to point between the universities.

Theoretical particle physicist Hitoshi Murayama has been on the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, for nearly two decades. Five years ago he became founding director of the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe at the University of Tokyo. ‘I feel strongly about being a liaison between Japan and the rest of the particle-physics community,’ says Murayama.

PT: Why did you decide to get involved in the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe [Kavli IPMU] at the University of Tokyo?

MURAYAMA: I have to say I was framed into it. When Japan was looking to start this WPI program [World Premier International Research Center Initiative; see Physics Today, December 2008, page 28

But even though I didn’t really want to volunteer, and was not enthusiastic about [being the Kavli IPMU director] myself, I actually resonated with the objectives. There has been a sense that Japanese academia has been fairly closed, not visible enough, despite very high quality research. So if I could play some role in connecting the two worlds, namely make Japan much more open and connected with people from the US and Europe, that would be a worthwhile thing to do.

PT: How do you split your time?

MURAYAMA: My role in Japan is not an academic position but rather administrative. So there are a lot of day-to-day operations going on. I have to go there for things like reviews, to see the university administration, the president, to go to funding agencies. So I end up going back and forth pretty much all the time.

It works out to about 50–50. I arrange it so I don’t miss teaching [in Berkeley]. My mode of operation when I am in Berkeley is to teach during the day, work with graduate students, come back home, have dinner, and then, when Japan comes into business hours, connect over video. I am kind of working on two shifts.

When I am in Japan, I talk to my students [in Berkeley]. There are many ways of staying connected. We can talk to each other as if they are right in front of me. I can pan my camera. If they write something on the blackboard, I can actually pan my camera and look at it, zoom in, zoom out. It’s very efficient, actually.

PT: What are the benefits of your dual responsibilities?

MURAYAMA: My research is expanding in a way I had not imagined. I am trained in theoretical particle physics, but now I am involved in research in condensed-matter physics. I am involved in putting together instruments for astronomy. Because the purpose of the Kavli IPMU is really to address questions about the universe from multidimensional perspectives, it gives many different tools and approaches. And even though my role is administrative, still I learn a lot on the science side.

I am the PI on a new multiobject spectrograph for the Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. That would have been unimaginable just a few years ago.

When you have new encounters with people, new encounters with subjects, new encounters with money, unexpected things can happen.

PT: What are the disadvantages?

MURAYAMA: The frequent trips are exhausting. And of course, my family is not very happy with me being away so much.

PT: Is there anything you would like to add?

MURAYAMA: I am sort of bridging between the US and Japan for the International Linear Collider. There are many things you can do just by knowing people and knowing the system on both sides, which would otherwise be quite difficult to do. I hope I can be a good bridge due to my experiences on both sides of the Pacific.

Lidia Smentek is now a professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, but for nearly 20 years she divided her time between there and her home base at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toru?, Poland. A theoretical physicist, Smentek focuses on lanthanide systems. Her life has been rife with stress, including enduring long absences from her husband and daughter, surviving serious illnesses, and being ostracized and ultimately forced to retire from her permanent position at Copernicus University. Nonetheless, Smentek says, ‘the final outcome is positive,’ and she would do it all again. She notes that ‘not many people have the chance to combine the experience on both sides of the ocean.’

PT: How did you start commuting between Toru? and Tennessee?

SMENTEK: The beginning was in 1982, when I came as a postdoc to Vanderbilt [University]. The atmosphere at my institute [Nicolaus Copernicus University], created by Aleksander Jablonski—the author of the Jablonski diagram of luminescence—was that you have to go abroad to be experienced, to collaborate, and to be able to climb the ladder of science.

I had an invitation to visit the computer science department. This was based on personal connections. My PhD adviser had met Charlotte Froese Fischer in Waterloo [in Ontario, Canada], and she had moved to Vanderbilt, so I was invited by her. At the time there was martial law in Poland; it was like a military state. This is why it was so difficult to follow a scientific path—I had to leave my family. This was not my choice, but the situation under the communist system. I left my six-year-old daughter and came for one year.

I arrived in the beginning of May. The first time I was able to call home was Christmas because there were no connections, and letters were censored—who knows by whom? I was getting letters with some words inside marked in black! Even now I want to cry when I think of my daughter saying, ‘Mom, tomorrow is Christmas, and you are not home.’ It was very difficult.

I met people in the chemistry department, and after I went back to Poland, we continued to collaborate. I came for the summer in 1985 and 1986—I could get permission only for the summers because of my teaching obligations at Copernicus during the academic year.

In 1989 I had a stroke, and took a one-year medical leave. Then, after completing my habilitation in 1993, I got an appointment as adjoint professor at Vanderbilt, which meant that my primary appointment was somewhere else.

PT: What did you like about coming to Vanderbilt?

SMENTEK: I used computers, equipment, the library, and could collaborate with people. I was free to do research, without teaching duties, and [was] far from local politics [at Copernicus], and then after some time, I would go back to my roots.

PT: How did you split your time?

SMENTEK: I was coming to the US in the middle of June and going back to Poland in time to teach, which starts in October. Under the rules of the chairman of the institute before the late 1990s, it was better, because I had advanced courses, and it was possible to have them during one semester. So I would take a leave of absence for one semester, doing research here, and publishing papers with both affiliations. I would also come during the break between semesters in the month of February.

PT: What happened then?

SMENTEK: In 1989 there were political changes in Poland following the success of the Solidarity movement. In the beginning, it was fine in my university. But then scientist-activists jumped in. This was the only crew which was very well trained as far as organization. Starting in around 2000 they were once again in power.

I am a witness of the past, and furthermore I am independent—not part of the local network. Especially because I had the appointment at Vanderbilt, they tried to remove me. With my scientific achievements and collaborations, I was creating a bad comparison for others. They succeeded in 2010. The dean, a former colleague, and the chairman—who by the way was my student in the past—wrote to the chancellor that I should be fired. Because I have the title of professor, which is for life and is given by the president of Poland, only the minister of higher education can fire me. It’s beyond the power of the chancellor. So they wrote to the minister, and I got a letter from the minister [saying] that the university will not support a scientist without achievements. This was written just after my publication in Nature Chemical Biology—one of my many publications. I retired within two days. But I think I was fired.

PT: What happened next?

SMENTEK: I moved to Nashville permanently. Since 1994 I had an appointment at Vanderbilt, but without salary. I couldn’t accept any money here because I was paid in Poland. Now since I retired over there, finally I can accept money here. I am hired, but not on tenure track. I teach a graduate course here and enjoy working with PhD students.

Thank God, now I am happy. I have peace. I have collaborations and fantastic conditions to work. I have a recent grant from NSF for my research on the structure and spectroscopic properties of lanthanide super small nanomaterials.

On the personal level, things also worked out well. In 1994 I married Andy Hess, a professor of chemistry at Vanderbilt. I met him in 1982, with no idea that in the future we would be together. Also, my daughter later came to study at Vanderbilt; she is a journalist and lives in the US. In 2002 I survived cancer. My mother passed away in 2003, so after that I didn’t feel I had to stay in Poland because of family obligations.

Everything is fine. From time to time, however, I am wondering whether I would have to go through such struggles if I were a man.

Mukhles Sowwan joined the faculty of Al-Quds University in East Jerusalem in 2004. Since December 2011 he has been dividing his time between there and Japan, where he heads up the Nanoparticles by Design unit at the new Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. His focus is on designing metallic and semiconducting nanoparticles for basic research and applications. For him, the arrangement brings access to more money, better equipment, and easier collaborations, and it allows him to help his home-country lab. ‘It’s a win-win situation,’ he says.

PT: Tell me about your background and your lab at Al-Quds University.

SOWWAN: I did my PhD in solid-state physics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Then I did a postdoc there. Then I moved to Al-Quds University in East Jerusalem. I established the first nanotech lab there. We design, fabricate, and study nanoparticles for nanotechnology and biomedical applications.

It is a successful lab through my collaborations with people around the world. But we lack advanced instruments. A transmission electron microscope, for example, costs more than $5 million. There is no way I can get at once that much money. I collaborated with scientists at Hebrew University. This was helpful, but still it was difficult to get my students from East Jerusalem to West Jerusalem because they need security permission to enter Israel.

We do not have a PhD program in Palestine. We don’t have the appropriate infrastructure. We have good teachers in Palestine but not enough good research labs. And my students are really good. One of my students is finishing his PhD at the University of Technology Dresden. I have others in France and Taiwan. I send my students to my collaborators.

PT: What attracted you to join the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology [OIST]? What are the professional advantages to holding two positions?

SOWWAN: It was during my sabbatical year at Stanford [University], when OIST started to recruit scientists. They called for scientists, and I interviewed, and it happened.

At OIST in Japan, I have better opportunities to apply my dreams and scientific ideas because there is better support and better shared facilities. There I am designing and fabricating nanoparticles that you can’t find elsewhere.

The other main advantage is that I will not abandon my unit at Al-Quds. I have had offers from industry and elsewhere, but this is the first time I got an offer where I could keep my lab, which I am proud of and want to support. So with this opportunity, I can do cutting-edge research in Japan and continue to develop my lab at Al-Quds.

PT: How do you coordinate labs in Japan and East Jerusalem?

SOWWAN: I spend half or more of my time in Japan and the rest at Al-Quds. It’s according to a joint research agreement [between the two institutions]. I have flexibility. And if I am in Al-Quds, I am still doing work for OIST, and vice versa. Some patents and publications will be joint, and some financial and technical support from OIST can be used for work at Al-Quds. It doesn’t matter where I am physically. Both universities benefit from my work, and I split my time as needed.

For me, the key is group leaders and good researchers in each lab. Group leaders facilitate things on the ground and make sure everything gets done according to my plan. I am in contact with my group leaders on a daily basis. I have one at each site. I also have administrative assistants—otherwise, I would be burned out.

Also, I avoid short-term travels. A few days can burn your time and kill your body. I plan to spend a month or more when I go from OIST to Al-Quds.

PT: Can you elaborate on how your Al-Quds lab will benefit?

SOWWAN: With the planned joint PhD program, I hope that we will enable students to do most of their research at Al-Quds but come to Japan for three or four months a year. This will be very relevant for female students. In conservative societies like Palestine, usually families don’t agree to send female children abroad. But if it’s for a few months, they will send a brother or husband with her. I insist on giving female students an opportunity to do a PhD. This is a mission.

Also, students in Al-Quds can work on collaborative research projects with OIST. I can support three researchers at Al-Quds for the cost of one researcher in Japan. And they [at Al-Quds] are talented, have expertise, and can, for example, characterize materials using the available equipment in my lab.

PT: What are the personal advantages and disadvantages?

SOWWAN: The main hardship is that I miss my mother. But I talk to her on Skype each day, without missing any day.

PT: Is there anything you want to add?

SOWWAN: Always on my mind is time management. I think I know how to have work limits, and because of that, I enjoy life more. I love my work, but after work, I get out of my unit happy and ready to go home, kiss my wife, and go out with her. Each day I learn something about this mysterious culture [in Japan], this land, this way of life.

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org