Japan Funds New Cosmic-Ray Detector in Utah

DOI: 10.1063/1.1825265

The new Telescope Array (TA) in Utah will combine fluorescence and scintillation detection methods used in earlier experiments to resolve a discrepancy in the observed rates of ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays. “Looking with both methods simultaneously should settle this,” says the University of Utah’s Pierre Sokolsky, a spokesman for the US–Japan collaboration. “If there’s no cutoff in the energy, there will be quite a lot of excitement. If there is, then we have some understanding. It’s been a burning question in cosmic-ray physics for 30 years.” (See Sokolsky’s article in Physics Today, January 1998, page 31

Ground was broken in late August for the first of TA’s three fluorescence detectors. Fluorescence from atmospheric nitrogen relaxing to the ground state is used to reconstruct the energy and directional origin of incident cosmic rays as a function of atmospheric depth.

In addition to the fluorescence detectors, which are scheduled to be up and running next year, TA will have 576 scintillation detectors spaced at three-quarter-mile intervals. The scintillators record charged particles produced by cosmic-ray showers and are similar to those used in Japan’s now defunct AGASA experiment. The fluorescence detectors are based on the High Resolution Fly’s Eye (HiRes), located on the US Army’s Dugway Proving Ground, about 90 km north of TA.

TA is designed to record cosmic rays with energies of 3 × 1018 eV and higher. Over times normalized for the experiments’ sizes, AGASA scientists recorded 12 events above 1020eV, whereas HiRes spotted only 2. “This is statistics of small numbers, so the overall discrepancy is nothing to talk about. Yet if it’s true, these 12 events would tell us something is wrong with our understanding of how the physics works,” says Utah physicist Kai Martens. “In any case, we don’t know the sources [of the highest-energy particles].”

The TA team needs permission from the federal Bureau of Land Management to place the scintillators on government land. Another hurdle is money. Japan has committed $12 million, but the University of Utah and other US partners are still trying to rustle up an additional $6 million. TA is being built in Utah because it’s high, dry, and dark. Japan is too humid and crowded for the experiment, says TA cospokesman Masaki Fukushima, a physicist at the University of Tokyo’s Institute for Cosmic Ray Research.

Scientifically, TA overlaps with the much larger Pierre Auger Observatory. Also a hybrid, Auger couples fluorescence detection with an array of water tanks that record Čerenkov radiation caused by passing muons. Auger’s Southern Hemisphere facility is getting started in Argentina; Utah and Colorado are the prime candidates for Auger North. “Auger really aims at the highest-energy events—it requires the largest possible area—and their global understanding,” says Auger spokesman Johannes Blümer of Karlsruhe University in Germany. The distribution of matter and sources of ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays are bound to be different in the two celestial hemispheres, he adds.

Although Blümer says he sees no “threat to Auger North by TA,” some particle astrophysicists worry that, with budgets tight, the new experiment could make it more difficult to secure funding for Auger North. But Sokolsky, who is a member of both projects, says TA “is a windfall for the US. Would people really rather not have the $12 million from Japan?” TA has narrower goals than Auger, he says. “If we work this right, we can use TA to help Auger.” Adds Martens, “The hope for Utah really is that we get Auger North here. Then we will combine three techniques and have a higher density of counters on the ground.”

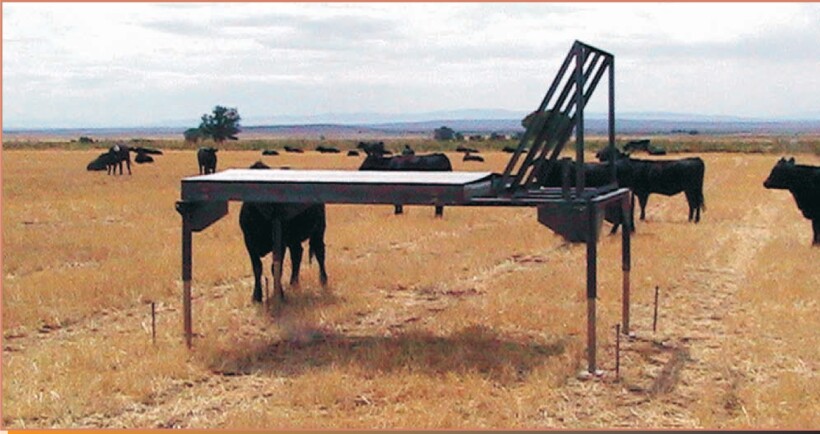

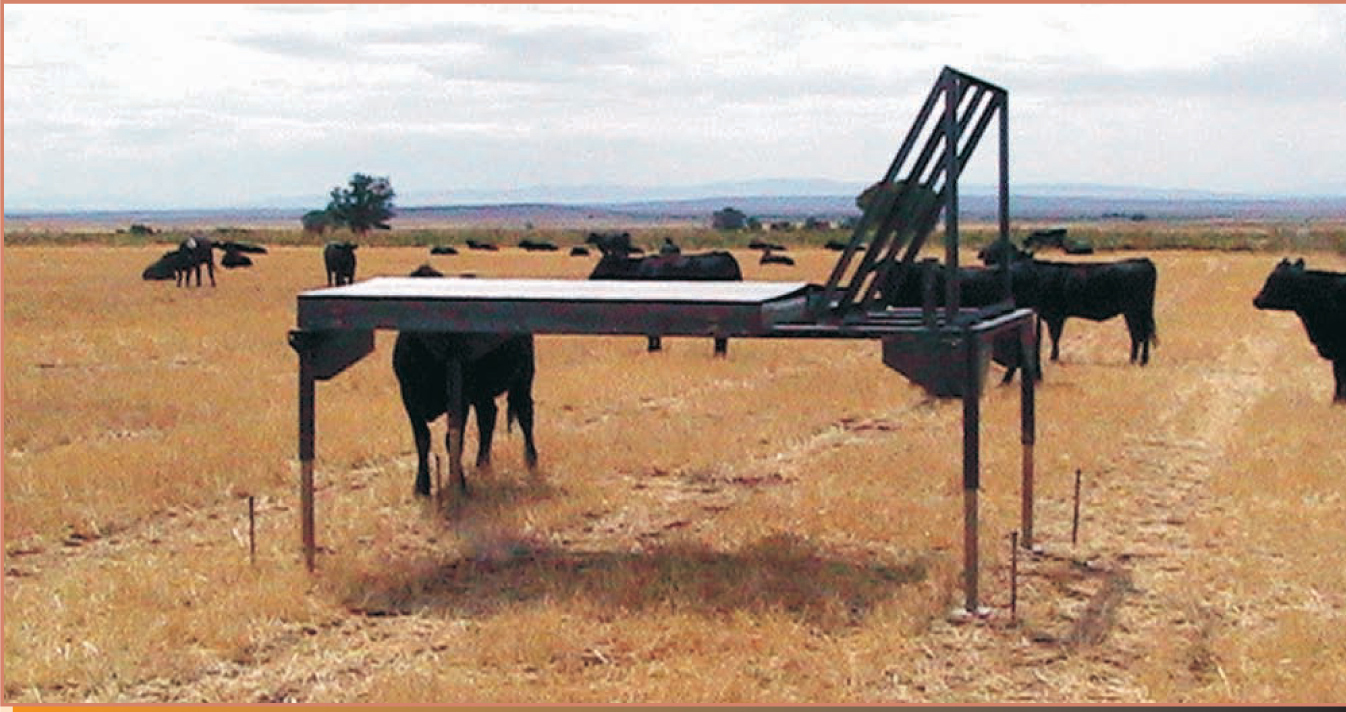

Solar-powered scintillators for the Telescope Array will sit on platforms scattered around the central Utah desert.

TIMOTHY ARNOLD

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org