IUPAP celebrates a century and strives to meet new challenges

Attendees of IUPAP’s centennial symposium gathered at the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy.

IUPAP

Connect with young physicists. Focus on sustainability. Partner with industry. Those are some of the new directions being pursued by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) to continue fulfilling its 100-year-old mission, which is “to assist in the worldwide development of physics, to foster international cooperation in physics, and to help in the application of physics toward solving problems of concern to humanity.”

IUPAP is a global organization that launched a century ago with 13 member countries; it now has 64 territorial members. It has always sponsored conferences—the International Conference on High Energy Physics, the International Conference on Statistical Physics, and the International Nuclear Physics Conference are prominent examples—and it has long-standing traditions of setting standards for units of measure, naming new elements, and awarding prizes. During the Cold War, IUPAP helped connect scientists across the Iron Curtain, according to Yves Petroff, who was president of the organization from 2003 to 2005.

In July IUPAP celebrated its centennial with a three-day symposium at the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy. (The union relocated its headquarters to Trieste from Singapore last year.) The event included a mix of talks and panels covering the history of IUPAP, hot areas in physics, science policy, physics education, women and underrepresented groups in physics, physics in different world regions, the nuclear threat, and climate change. More than 250 people from some 70 countries large and small, rich and poor, attended; about 40% participated in person, with the rest online.

Since the late 1950s, IUPAP has promoted the free circulation of physicists. In line with that value, this past March the union offered scientists from Russian institutions the option to use an IUPAP affiliation when they attend meetings supported by IUPAP. The affiliation is a way around the objections that many non-Russian scientists and their institutions and governments have to interacting with researchers affiliated with Russian institutions since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February (see Physics Today, June 2022, page 22

To use the IUPAP affiliation, scientists must state that they are “not actively supporting the war,” says IUPAP president Michel Spiro, a French particle physicist. Physicists in Russia can sign such a statement without being jailed, he explains, because Russia calls the situation a “special operation,” not a war. Still, he says, he was nervous about whether the affiliation arrangement would pass as a resolution on 14 July at the IUPAP General Assembly, which followed the centennial celebration. Another resolution made Ukraine IUPAP’s newest member. “It was a delicate meeting,” says Spiro. “But the resolutions passed.”

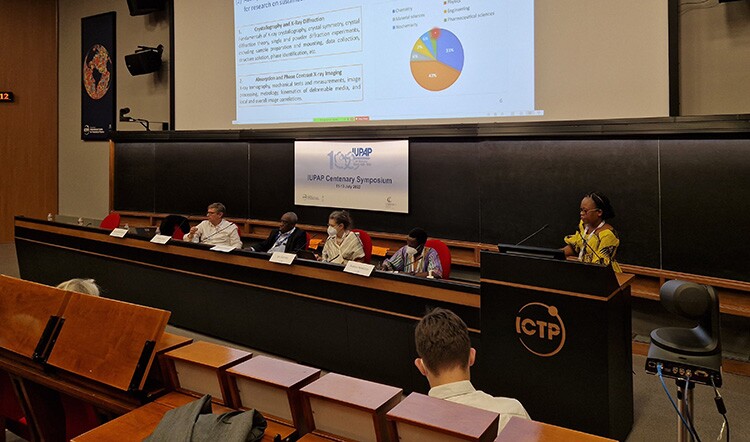

Marielle Agbahoungbata, coordinator of the X-TechLab in Benin, gives a talk during a 12 July session about the work of IUPAP members in Africa and the Middle East.

IUPAP

In the past two decades, the union has emphasized diversity and inclusion. In 2002 it put on the first International Conference on Women in Physics (see Physics Today, May 2002, page 24

In 2016, jointly with the International Union of Crystallography, IUPAP launched LAAAMP—Lightsources for Africa, the Americas, Asia, Middle East, and Pacific—to enhance advanced light sources and crystallographic sciences in underserved regions. The union also promotes open-access publication, data, and software, in line with recommendations by UNESCO.

IUPAP officers say they are reflecting on how to remain relevant and serve the needs of physicists around the world in a changing geopolitical and social environment. For example, the union’s working group on women in physics has expanded its mandate to address gender and intersectionality issues more widely. Finding ways of being inclusive and expressing inclusiveness is still a work in progress, says Gillian Butcher of the University of Leicester in the UK, who chairs the working group. “We want to incorporate other underrepresented groups.”

In November 2021, IUPAP welcomed into its fold the International Association of Physics Students. Run by and for students, IAPS has more than 90 000 individual undergraduate and graduate student members around the world. At the IUPAP centennial symposium, eight IAPS representatives deftly handled logistics of presentations and ran around providing microphones during question periods. More important for IUPAP, though, is the access to early-career physicists that comes with IAPS’s new status. “We can learn from them,” says IUPAP president designate Silvina Ponce Dawson of the University of Buenos Aires.

For their part, physics students who become involved in IAPS can have a front-row seat at high-level IUPAP community discussions, and they get to share their perspectives, gain networking possibilities, and access IUPAP travel funds. Ruhi Chitre, who completed her bachelor’s degree at the University of Warwick last year, is the current IAPS president. She hopes the link with IUPAP will raise IAPS’s profile and attract more students from more countries.

Silvina Ponce Dawson (left) will succeed Michel Spiro as IUPAP president.

IUPAP

Through a new initiative begun in 2017 and made official last year, IUPAP is seeking to build closer connections among physicists in academia, industry, and national and international research laboratories. The Physics and Industry working group’s mandate includes helping in “the application of physics to solve problems of concern to humanity,” says Christophe Rossel, a retired physicist from IBM Research–Zurich who is leading the effort. So far, he says, two organizations have signed on: CERN and the Advanced Laser Light Source in Quebec.

IUPAP is also considering accepting low-income territories as associate (nonvoting) members. Some countries or parts of the world have very small physics communities, explains Ponce Dawson. In such cases, individual physicists may want to join IUPAP, but their government may hesitate to pay the dues. The territories approach would allow small communities to join at lower cost. Focusing on territories, she says, avoids conflicts about whether a place is recognized as a country, and it allows participation by regions. Nepal and some of the Pacific Islands, for example, could be potential new members.

Other expansions in store at IUPAP may involve explicitly promoting specific physics topics of interest, such as climate change or quantum information. The union could do that through conferences and prizes, Ponce Dawson says, and possibly through more concerted projects along the lines of the LAAAMP initiative or the Gender Gap in Science project

“I would like IUPAP to gain visibility and to act as a link among physicists from developed and developing countries,” says Ponce Dawson. “It could become a place where people can look for job opportunities and ideas for teaching and also a liaison between physicists and policymakers—a place to spread information about physics and physics practice. IUPAP looks to its future with renewed impetus.”

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org