Interpreting art to teach science

DOI: 10.1063/1.2911171

After 35 years of lecturing and researching, “you get fed up. It becomes boring!” says Abraham Tamir. So, for the past 10 years, the professor of chemical engineering at Ben Gurion University in Beer Sheva, Israel, who has published 10 books and 165 scientific articles, has been lecturing, setting up exhibitions—including a museum at his own institution—and writing columns on the interplay between art and science.

“I am always looking, looking, looking,” he says. “If I go to an art gallery, I’m looking for science in the art.” Unlike some artists and scientists who explore connections between the fields, Tamir is not looking for art that derives from science or mathematics. Instead, he looks for ways that art illustrates scientific concepts. His goals, he says, are to get people to appreciate art more and to understand science better. Recently, Physics Today asked Tamir about his newfound passion.

PT: How did you become interested in using art to explain science?

TAMIR: When I was about 15 years old, my parents told me to learn art. I took courses in high school, and this gave me knowledge and interest in art. After many years teaching and researching in chemical engineering, I started to get interested in the interactions between science and art.

I developed a course and taught it at our university. I teach it to students in various disciplines—they don’t have to know anything about art or science. The idea is to describe scientific subjects through art—to educate people so that when they are looking at pictures, or artwork, they should try to see what scientific subject is hidden.

PT: What are some examples?

TAMIR: I demonstrate Newton’s third law—action is equal to reaction. If a painting shows a person standing on the floor, he is pushing the floor, and the floor pushes back. If there were no counter force, everything would fall into the floor. The order in the universe indicated by this and other basic scientific laws hints at some godlike force—only for scientific reasons do I believe in God.

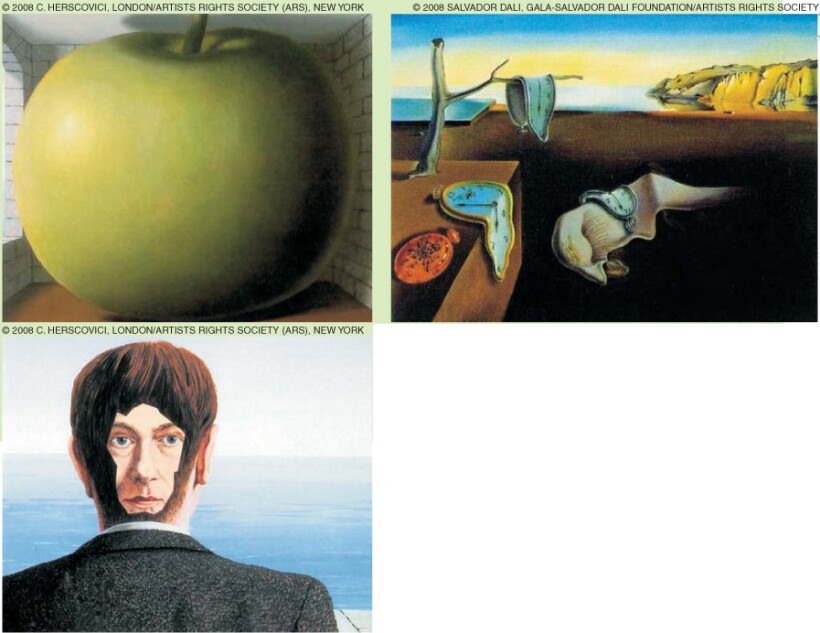

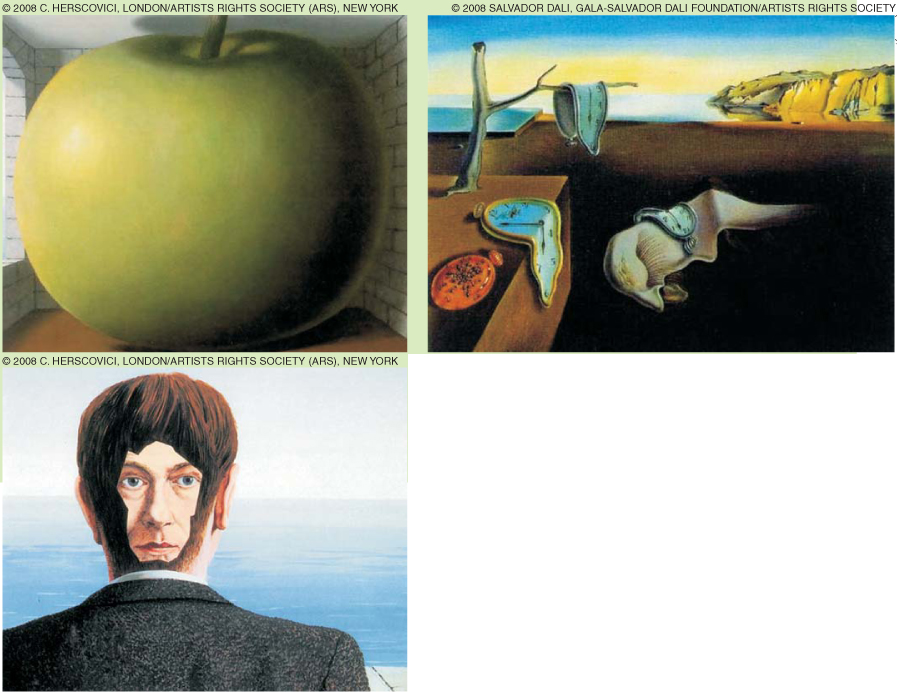

Another example is Einstein’s theory of special relativity. When you move at the speed of light, mass approaches infinity, thickness shrinks to zero, and time stretches. It’s not so easy to understand this. However, there is a famous picture [by René Magritte] in which an apple fills the room—that can represent mass going to infinity. And there is a very nice picture by Salvador Dalí of watches oozing like Camembert cheese—time stretching. And in a painting by Magritte you see the front of a man’s face from the back. In Einstein’s theory this means that near the speed of light, thickness shrinks to zero. With these three pictures, I demonstrate Einstein’s model.

PT: What other topics do you cover in your courses?

TAMIR: I give an introduction about art and science. I talk about the human brain, mathematics, symmetry, perspective, and fractals. In chemistry I discuss DNA, water, and other substances. In the life sciences, botany, zoology, evolution, twins, cloning, medicine, cancer, genetics, the human body. In the natural sciences, I use artworks to discuss matter, gravity, sound, light, shadows, colors, surface tension, time, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, Ohm’s law, thermodynamics, fluid flow, and many other subjects.

PT: Your interpretations seem very subjective; what are you trying to achieve?

TAMIR: I am trying to bring to the attention of people the possibility to identify scientific subjects in artworks. In particular, I want students to gain appreciation of art and science. In my experience, once you demonstrate the laws of science with art, you remember them better. If the students wouldn’t have liked the course, they would say ‘You are a nice guy, be healthy,’ and they would not come to my course. But the course is popular, and now I teach it at different places.

Tamir

Relative art. In Abraham Tamir’s classroom, scientific concepts such as special relativity are taught with art. The apple in René Magritte’s The Listening Room represents mass going to infinity; the clocks in Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Time show time stretching; and the face in Magritte’s The House of Glass is an example of distance shrinking at relativistic speeds.

(ARS, NEW YORK)

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org