Grants to women come up short in pilot study

DOI: 10.1063/1.2784678

In nuclear theory, women get about 50 cents for every dollar men get in grant money from the US Department of Energy. Why the discrepancy? And does it exist in other physics subfields too?

The American Physical Society’s (APS’s) Committee on the Status of Women in Physics decided to see how things stood for physics after learning that two studies—from the Government Accountability Office in 2004 and RAND Corp in 2005—found that some agencies, notably the National Institutes of Health, give smaller grants to women than men. The GAO study reported a “serious data limitation” from DOE, a major funder of physics research, so the CSWP started there.

“We picked one subfield, nuclear theory, for a pilot study because we had anecdotal information about problems in that area,” says Roxanne Springer, CSWP vice chair and a nuclear theorist at Duke University. Later, DOE worked with the CSWP on a more complete analysis of the same data—comprising 57 research grants from fiscal year 2005. That includes individual and group grants, with awards to a total of 103 investigators, 9 of them women.

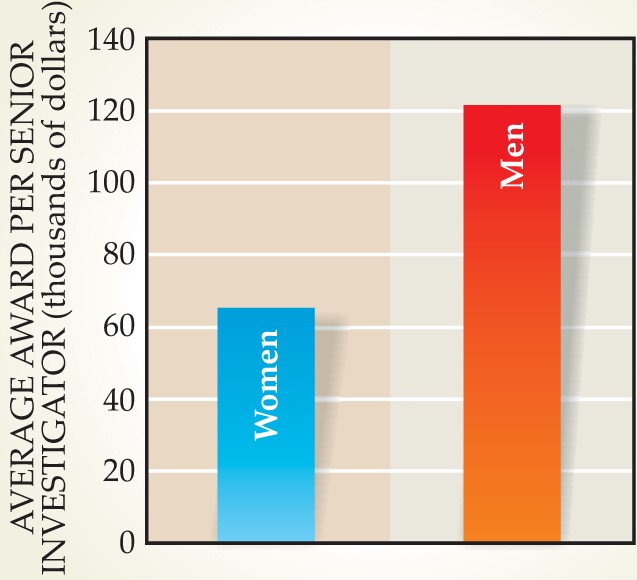

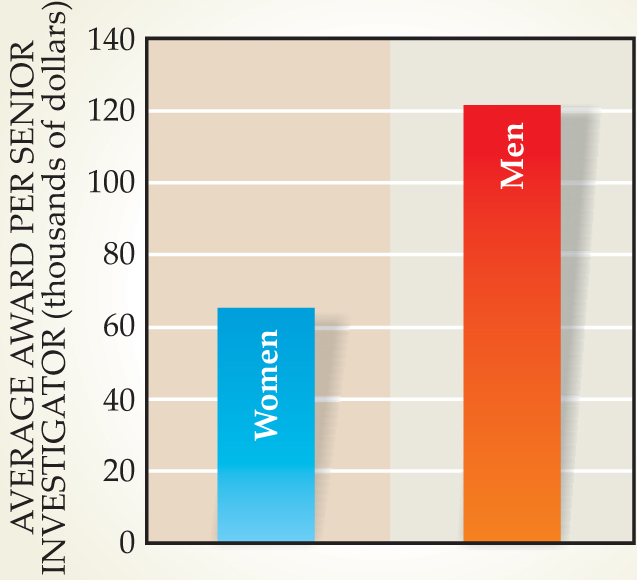

The analysis revealed that men got $123 850 per year on average, compared with $64 310 for women. The average for group grants was slightly higher than for individuals, but the gender disparity remained.

The discrepancy may be due to women asking for less. According to Sidney A. Coon, DOE program manager for nuclear theory, “Both men and women got about 80% of what they asked for. Men ask for two and a half times as much as women.” That, he says, “begs the question of whether [women] have low-balled their request.” Adds Sherry Yennello, a nuclear chemist at Texas A&M University and past CSWP chair, “There is social science literature that says women tend to ask for less than men. There may also be coaching involved. If women are asking for less then men, why is that so? This is the next set of questions.”

Springer and Yennello also analyzed the time since earning the PhD to see if seniority would explain the discrepancy in award amounts, but they found no correlation. Another contributing factor, says Springer, is that “you’ll probably find that the largest funding per person occurs at the highest-ranked nuclear theory groups. And historically speaking, those groups don’t tend to have women.”

Springer says she wasn’t surprised by the funding discrepancy. “Maybe nuclear theory is unusual, maybe it’s not. Either way, it’s worth taking a look at the data across all fields,” she says. “We want people to become aware of any discrepancies and their causes. Funding may be only a part of the problem.”

The robust turnout of representatives from DOE and other funding agencies at APS’s workshop on gender equity this past May (see Physics Today July 2007, page 35

“Our funding should reflect the value to the scientific community and the impact of the science that we fund,” says Coon. It’s premature to make a firm statement, he adds, but from a citation analysis, “my memory is that we were seeing value from women—they were having an impact out of proportion to their funding.” Coon notes that even before the nuclear theory data was looked at, DOE’s Office of Science had begun planning for a system to track voluntarily provided demographics of grant applicants and awardees.

Average awards to men and women in nuclear theory in fiscal year 2005

SHERRY YENNELLO

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org