Goodbye, bifocals?

DOI: 10.1063/1.2349727

An ultrathin liquid crystal layer sandwiched between layers of glass could render bifocals obsolete, say optical scientists at the University of Arizona and Georgia Institute of Technology in a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“When we are young, we can look at objects at different distances—we can read, look at the computer, or drive—and our eyes compensate and focus everything to the retina,” says Arizona’s Nasser Peyghambarian. With age, the eye muscles get stiff and lose some of their responsiveness, leading many people to need eyeglasses. Nematic liquid crystals could adjust for focal length and thus correct for both near- and farsightedness, as well as for other aberrations in vision, he says.

In liquid crystals, the refractive index, which determines by how much light is bent, changes with applied voltage. The trick is to program a microelectronics chip to control the applied-voltage pattern to correspond to the accommodation needed by the wearer. The chip could be reprogrammed to adjust for changes in eyesight, so that one pair of liquid crystal eyeglasses could last a lifetime.

In the prototype glasses, a 5-µm layer of liquid crystal is sandwiched between transparent electrodes deposited on glass slabs 0.5 mm thick. Voltages of 2 V or less are applied, with changes in the index of refraction occurring in fractions of a second. The eye-glass wearer would not notice any focusing delay, Peyghambarian says.

“Vision correction has stringent requirements, such as large aperture, fast response time, high light efficiency, low operation voltages, and power-failure-safe configuration,” says Arizona’s Guoqiang Li. The team’s prototype with liquid crystals is the first such effort “that is practical for vision correction,” he adds.

In the prototype, the applied voltage comes via a bulky chip that is switched on and off manually, but eventually, says Peyghambarian, the glasses “would be adapted with a range-finder mechanism, so that things at different distances would automatically come into focus, like with an autofocus camera lens.” A Virginia company is exploring commercializing the glasses.

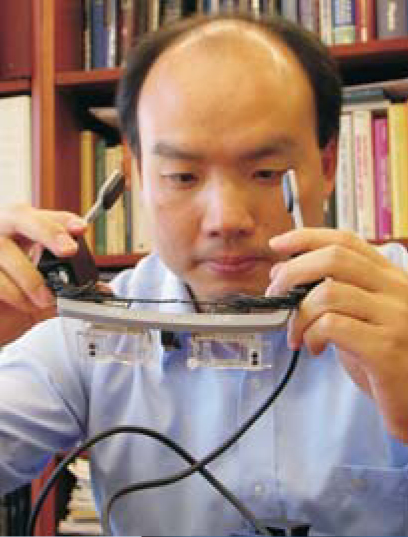

Researcher Guoqiang Li models prototype liquid crystal eyeglasses.

LORI STILES, UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA

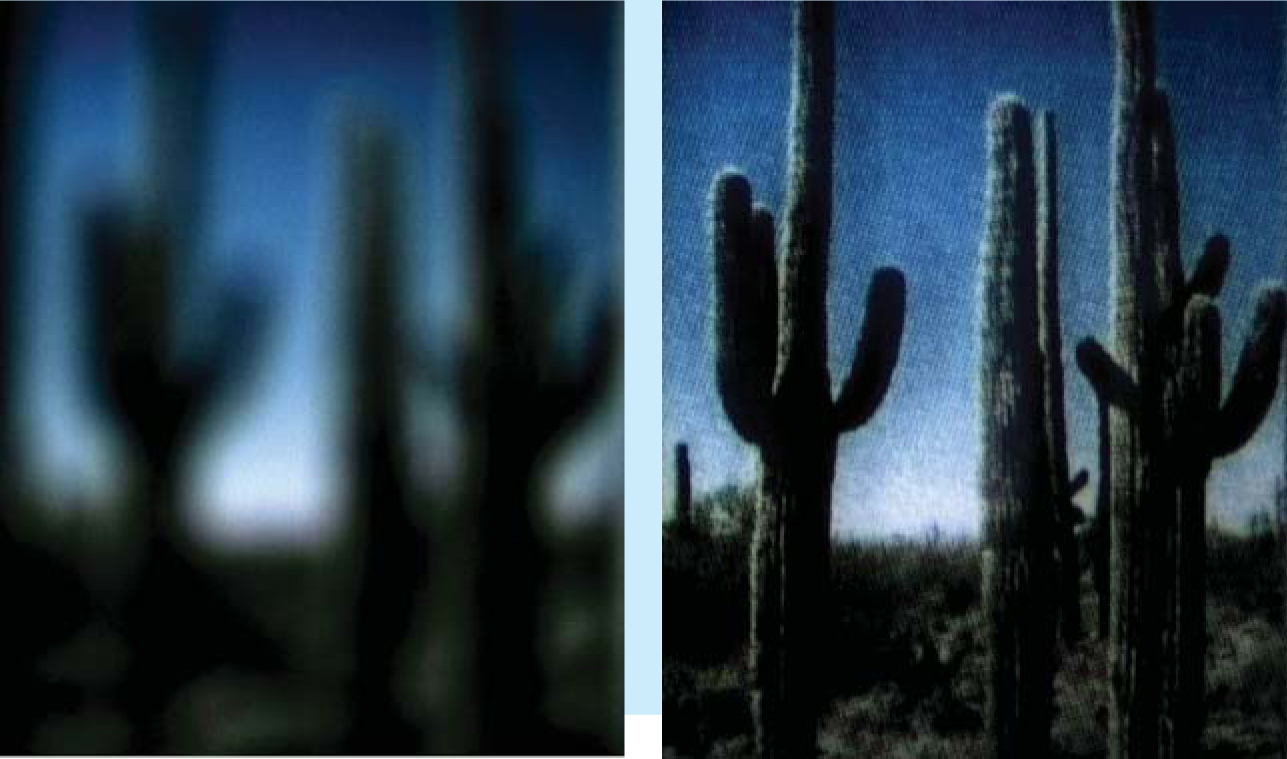

Cacti as seen by a model eye with (right) and without correction from an activated liquid crystal lens.

(Cactus images courtesy of G. Li et al.,

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org