Geological hazards are focus of Chinese research initiatives

DOI: 10.1063/1.2435672

The deadliest earthquake in modern times killed some 244 000 people in Tangshan, an industrial center about 150 km east of Beijing. Tangshan sits on what ought to be solid ground—the North China craton—but on 28 July 1976, a 7.6-magnitude earthquake struck. Now, 30 years later, understanding intraplate earthquakes such as the one that devastated Tangshan is a key thrust within a set of new Earth sciences initiatives for northern China.

“We have a lot of hypotheses, but we don’t know exactly why earthquakes happen in this kind of place,” says Mian Liu, a geoscientist at the University of Missouri-Columbia. “It’s not like the interplate motion in California, Indonesia, or Japan. Those places are tectonic boundaries.” Intraplate earthquakes occur less frequently, says Eugene Schweig of the US Geological Survey, who studies the New Madrid seismic zone in the North American craton. “And when they happen on these stable continental areas, the seismic waves travel much more efficiently through the Earth’s crust, so you can have shaking or damage over much larger areas for the same size earthquake.”

“Cratons are supposed to be geologically stable, not active,” says Peking University geophysicist John Chen. “We want to identify the spatial and temporal extent of the destruction of the [North China] craton. How much of the craton is destroyed? And over what period? It’s a first-order question of how the continent has evolved.”

Maximum impact

Craton evolution and related questions are part of the Underground Lightening—Craton Destruction Project, for which funding is expected to be $20 million over five years. In terms of funding, “this is by far the biggest project the National [Natural] Science Foundation of China has ever done,” says Chen. A decision on the project is expected late this year or early next. The buzz is that it has a 99% likelihood of being approved, and if it is, it will fund some 10 research proposals annually starting next year. For his part, Chen is keen to measure the thickness of the craton’s lithosphere—the crust and outermost layer of the mantle—which is known to be much thinner than that of typical stable cratons. “The structure beneath the surface is probably key,” he says.

Lithospheric thinning will also be studied as part of the Greater North China Initiative, which encompasses a wide range of geological research in North China. The GNCI was spearheaded by Liu and other expatriate Chinese scientists through an organization called International Professionals for the Advancement of Chinese Earth Sciences. “We were inspired by EarthScope [in the US],” says geophysicist An Yin of UCLA (see Physics Today December 2003, page 32

According to the expatriate group’s white paper, they focus on North China because it “hosts the most vital industrial, commercial, residential, and political centers” of China and because, with earthquakes, floods, droughts, and dust storms, it is “one of the most geologically dynamic settings in the world.” Among the research areas recommended in the white paper are the reactivation of the North China craton, including lithospheric structure and intracontinental earthquake prediction and preparation; volcanic activity; ground-water flow; and the coupling of tectonics to climate change. Says Yin, “How does a very old craton, with a thick lithosphere, become so thin? How does the thinned lithosphere interact with active faults? How often do earthquakes occur? What are their spatial patterns? All of this is completely unknown.”

No monetary figure has been officially put to the GNCI. But the initiative, Liu says, “is now a top priority in the National [Natural] Science Foundation of China.” (For a discussion of China’s 15-year science and technology plan, see the article on page 38.)

In parallel to the underground lightening project and the GNCI, the China Earthquake Administration has purchased some 600 portable seismometers, bringing the country’s inventory to more than 800. The scientific community, says Liu, “wants to map the hidden faults. Some do not break the surface. Those are the most dangerous.” Seismological imaging, he adds, “uses seismic waves traveling through the Earth—from earthquakes occurring anywhere. The seismometers provide a passive way to study the structure, like an ear that listens.”

A turning point

The funding and equipment for Earth sciences research represents “a turning point for China,” says Liu. In the past, he explains, most of the money and instrumentation for international collaborations studying geology in China has come from western scientists. “The heavy funding of the Chinese government in Earth sciences will be the envy of US seismologists. But it makes international collaboration much easier.”

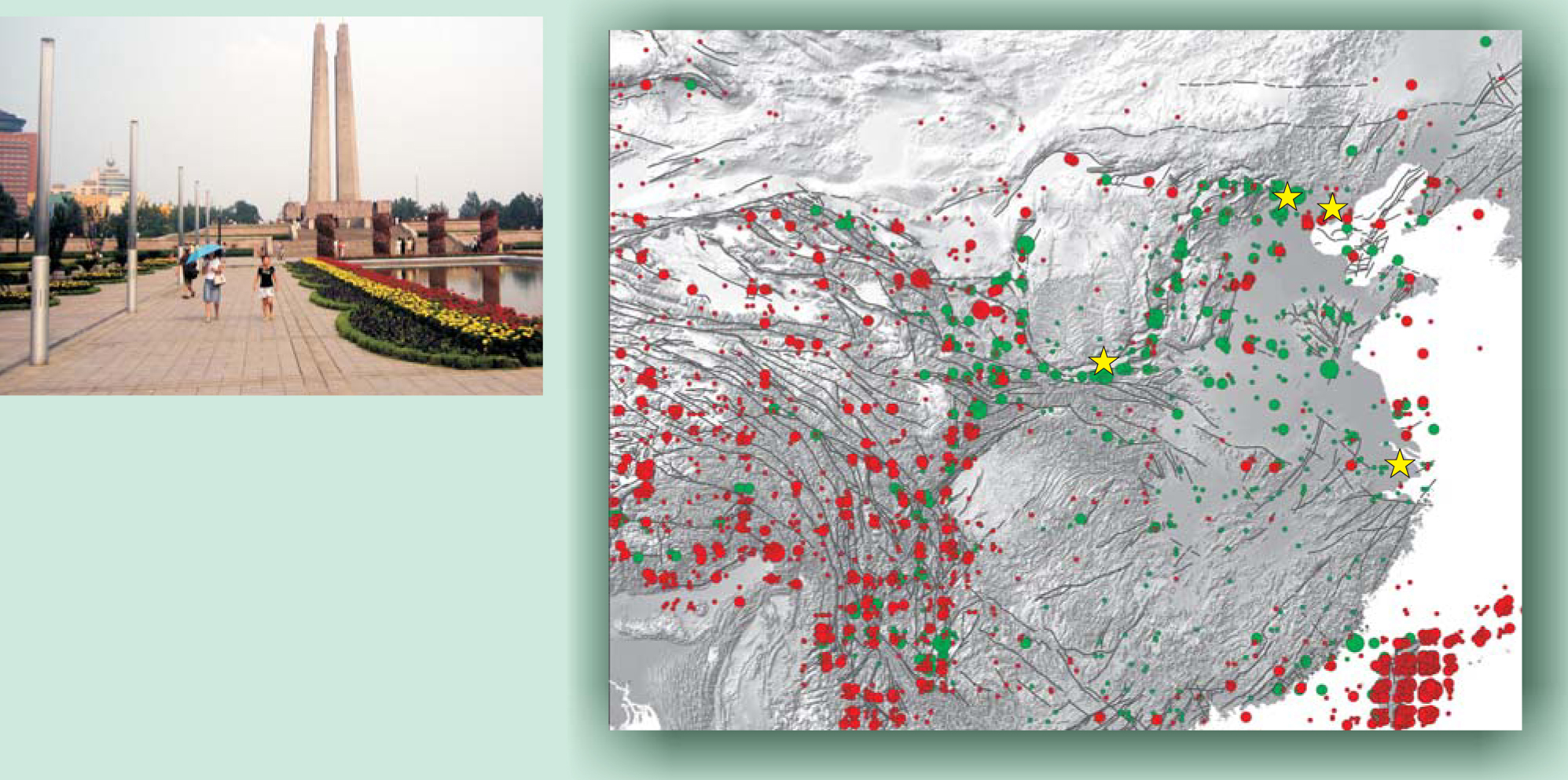

On this topographic relief map of North China and neighboring regions, red circles indicate the locations of earthquakes in the 20th century and green circles mark historic quakes going back 2000 years. Circle size is proportional to quake magn itude, and all marked quakes are magnitude 4 or greater. The yellow stars show the approximate locations of, from left to right, Xi’an (the ancient capital of China on the southern rim of the Ordos Plateau), Beijing, Tangshan—which all lie on the North China craton, a key area for geosciences research — and Shanghai. The island at the lower right is Taiwan. Memorial towers in Tangshan (above left) commemorate the earthquake that devastated the city in 1976.

(Annotated map courtesy of Paco Gomez, Youqing Yang, and Mian Liu./AN YIN)

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org