Equation changes for international STEM scholars deciding whether to come to US

For STEM scholars from around the world, time at a US university or research institution—as a PhD student, postdoc, or visiting professor, for example—has long been a sought-after stepping stone on the academic career path. “A BTA—‘been to America’—provides a leg up in getting a faculty job at world-leading institutions,” says James Fraser, a physicist at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and director of science policy and advocacy with the Canadian Association of Physicists.

But changes in US politics and research funding in recent years have shifted how scholars weigh whether to come to, or remain in, the US. And anecdotally, at least, hesitance has ramped up in 2025.

Alán Aspuru-Guzik grew up in Mexico and moved to the US for graduate studies in physical chemistry. In 2018, spurred by Donald Trump’s first term as president, Aspuru-Guzik left his tenured position at Harvard University for a post at the University of Toronto. The new normal for scholars is, he says, “I will not go to the US for a postdoc or faculty position.”

Alán Aspuru-Guzik (center, with hat) with the large, multidisciplinary group he leads at the University of Toronto in both theoretical and experimental research on quantum computer algorithms, molecular discovery, and more. He moved there from Harvard University in 2018 out of concerns regarding the direction President Trump was taking the US during his first term. Those concerns have escalated, he says, and his students and postdocs look outside the US for their next steps.

(Photo by Sean Caffrey.)

Nearly a year after applying for a tenure-track position in the US, a physicist on the verge of accepting the job decided at the last minute in August to stay in Germany. According to the chair of the department that the scientist would have joined, the candidate had been enthusiastic about the position and had wanted to get involved in NASA-funded projects. (The chair requested anonymity to protect the identity of the candidate.) But by spring 2025, the academic landscape looked different than when they had applied.

Three factors led the candidate to turn down the job, says the chair: With federal funding for science threatened, the candidate was worried about getting research grants; they wondered about the security of tenure in the US; and they feared that the US may no longer be safe for their spouse, who is not white.

“It used to be typical to go to the US” as part of one’s training, says German native Jannis Necker, who began a postdoc at Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands this past April. “It was a way to get your foot in the door of international projects.” But already during Trump’s first term, he says, “the political climate looked restrictive.” Now, he says, the US has lost appeal for him and many of his peers because of both the politics and uncertainty in funding. “The perceived value of going to the US has decreased,” he says.

Alexandra Trettin earned her PhD in her native Germany and is currently a postdoc in neutrino physics in the UK. “For me, the political situation, and in particular, the attacks on LGBT rights, made it completely unattractive to go to the US,” she says. “I had an offer in Texas,” she continues. “But as a trans woman, I didn’t feel I could live in the US safely, especially not in Texas.” Trettin says she avoids the US—she won’t go even for a conference out of fear of being hassled at the border—and that doing so comes with costs to her career. “It makes it harder to network.”

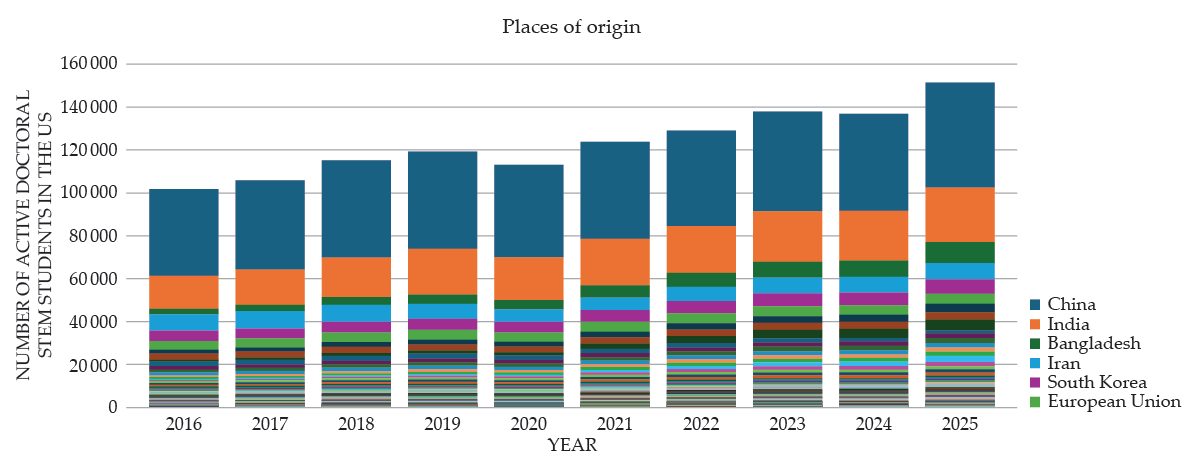

With the introduction of new visa hurdles, attacks on diversity, threats to research funding, and other US political developments, the academic community has widely expected the appeal of the US—and consequently, international enrollment—to fall. Despite such prognostications, international enrollment in US master’s and doctoral programs in STEM fields is up this year, according to data from the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS)

The total number of visas for doctoral students enrolled in US STEM programs is up this year, despite a trend to look elsewhere that is fueled by tightening purse strings and policies that have US universities on edge. The data are for active visas to people from about 200 countries in the fall of each year shown.

(Data compiled from the US government’s Student and Exchange Visitor Information System and analyzed by Michael Marder.)

The US remains a top choice for early-career scientists from lower-income countries. “They still want to come,” says a US-based physics professor who, as an immigrant from Pakistan, requested anonymity. But, says the professor, with many scholars experiencing visa issues, faculty members may not want to risk delays in the arrival of their graduate students or postdocs. “It’s a simple equation: If you have [grant] money, you have to deliver. If someone can’t come, take someone local, even if you sacrifice quality.” Another US-based physics professor who didn’t want to be identified notes that many students are coming from India (where the professor is from), but says, “Their parents don’t want them to. They are scared.”

For many years, “the US was the crown jewel for science,” says a researcher who came to the US from the UK in 2011 to do their PhD in ocean science and engineering. Their mentors advised them that in the US they’d have better funding and more freedom as a PhD student to develop their own research. In 2018, when it came time to seek a faculty position, the researcher turned down offers in the UK in favor of a tenure-track job at a top-tier US university, where they work on glacier and ice-sheet dynamics. (The researcher is in the process of getting a green card and requested anonymity to avoid calling attention to themselves.)

These days, says the researcher, international undergraduate and graduate students who are based in the US express doubts about staying in the country because of funding uncertainties. American students and postdocs, the researcher adds, are increasingly looking to leave academia and, sometimes, science. The researcher’s response? “Most of the time, I ask them if they are super passionate about science. And I help them focus on skills that they can transfer from their academic research to other workforce sectors.”