Found: ancient, primitive mantle from deep Earth

In 1869, during a rush to mine diamonds in the Kimberley region of South Africa, geologists named the peculiar igneous rock containing the valuable mineral “kimberlite.” The kimberlites contain high-pressure minerals that form deeper in Earth’s mantle than any other volcanic material. They occasionally erupt to the surface through long, narrow columns and thus offer rare glimpses into the elusive, deep-mantle region. Now Jon Woodhead of the University of Melbourne in Australia and his colleagues have used kimberlites to track the evolution of the deep-mantle source through time. Using isotope ratios of the elements neodymium and hafnium, the researchers discovered a subsurface region that would have formed early in Earth’s history, shortly after the core differentiated from the mantle.

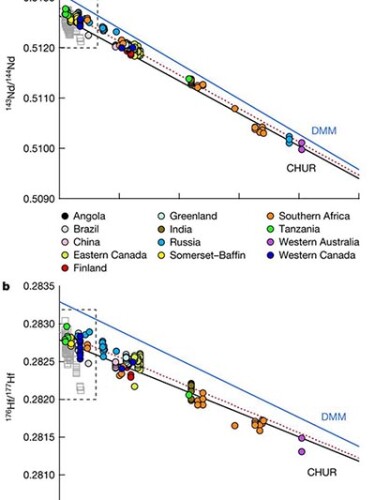

The kimberlites from which the researchers assembled the geochemical data erupted to the surface between 2.5 billion years ago and the present. Isotope ratios of 143Nd/144Nd and 176Hf/177Hf indicate the composition of the kimberlite source region, and the pair of graphs in the figure show how the ratios have increased over time. (Time progresses from right to left in the figure.) If the kimberlite source evolved with the bulk of Earth’s upper mantle, the data would plot on the blue (DMM) line, which represents modern-day magma compositions that erupted at mid-ocean ridges. Instead, the researchers found that kimberlites are more similar to the black (CHUR) line. That model tracks the evolution of chondritic meteorites, which formed in the early solar system.

Unlike data from other subsurface regions, the results here suggest that the kimberlite source has remained unmixed and chemically distinct from the upper mantle for most of Earth’s history. The increase in Nd and Hf isotope variation around 200 million years ago—bounded by the dashed box—may indicate a significant perturbation to the ancient reservoir. Although more and better age-constrained data are required to make definitive conclusions, Woodhead and his colleagues suggest that the blip in the data could be the result of subducting slabs of ocean crust descending farther and more frequently into the lower mantle. (J. Woodhead et al., Nature 573, 578, 2019

More about the authors

Alex Lopatka, alopatka@aip.org