Fermilab forms backup plan to avoid science gap

DOI: 10.1063/1.2800091

Anticipating delays with the multi-billion-dollar International Linear Collider, Fermilab wants to get started on R&D for a new $500 million–$1 billion accelerator so as to be poised to forge ahead with it if indeed the bigger project is held up.

The ILC—an electron–positron collider that would succeed the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which is set to come on line next year at CERN—is the priority, says Fermilab director Pier Oddone. “Our goal is to host the ILC, and we would like to see that move along and be decided as expeditiously as possible.” But, he adds, Fermilab is likely to shut down the Tevatron at the end of 2009, so if a decision is not reached to build the ILC soon after that, “the lab is in a peculiar position. And if you look at any historical international agreement, like ITER [the international thermonuclear energy reactor], it took many years to happen. So with a project of that scale, it’s prudent to prepare for the fact that we may actually be tied up in negotiations, site selection, and all sorts of things for a number of years.”

Intensity frontier

The centerpiece of Fermilab’s backup plan is Project X, which would produce a high flux of protons at 8 GeV that could be converted through collisions into high-intensity beams of neutrinos, muons, or kaons. “Project X would provide intensities of rare particles 3 to 10 times higher than currently available,” says Fermilab theorist Joseph Lykken. Neutrinos could be used with NuMI (Neutrinos at the Main Injector) and NOvA (NuMI Off-axis ve Appearance), respectively existing and planned detectors in northern Minnesota, while flavor and muon experiments would require new detectors.

“By probing CP violation, differences between neutrino and anti-neutrino processes, we hope we could figure out whether leptogenesis is true—whether all the stuff we see, all the stars and galaxies, was produced in the early universe from neutrinos,” says Lykken. Unification—the theory that quarks, neutrinos, and charged leptons are different facets of one kind of particle—is another big question that Project X could address, he adds. “We’ve seen oscillations in neutrinos and quarks, so if we see muons turning into electrons, that would tell us that this idea of unification is on the right track. And it would be important if it were true. It would tell us about the origins of the Big Bang and might tell us how to convert one type of matter into another.”

Not only would Project X offer exciting science, says Oddone, “but we have come up with a clever idea in which we basically build 1.5% of the ILC but use it to accelerate protons for the machines we already have here.” Because Project X would use the same type of superconducting RF cavities as the ILC, he adds, “we would be decreasing all the risks that are attendant to building such a big machine—we will be way ahead in industrializing the technology through Project X.”

Coordination or competition?

Although an early start on industrializing some of the technology that the ILC would also use “might help in getting the US to play catch up,” says Caltech’s Barry Barish, who heads the global design effort for the ILC, “if I ask if the [ILC’s] outstanding problems are addressed by [Project X], the answer is no.” Those problems are the need to achieve a high acceleration gradient, reliably industrialize the high-gradient cavities, and make the industrialization cost efficient, he says. “These are our three biggest problems. Project X doesn’t attack them.”

Barish also worries that in putting Project X forward, Fermilab is sending the world the message of a weakened commitment to the ILC. “A decision that preempts international judgment of the ILC is a very unhealthy thing,” he says. A second concern is that there is not enough expertise in the US for concurrent R&D on the two projects. “I’m worried about technical expertise—whether we will have to share a resource that we don’t have enough of.”

Oddone agrees that both personnel and the perception of diverting attention are concerns, but he says, “if we are ever so lucky to be in a position where the two [projects] are fighting each other, we clearly would go for the ILC.” A detailed design for the ILC, including the cost, should be ready in 2010. At that time, says Young-Kee Kim, chair of the Fermilab steering committee that proposed Project X, “we will see what we know about LHC data and the status of ILC international agreements. We think we will have a lot of information and should be able to forecast a timeline for the ILC. When 2010 comes, we will make a judgment.”

To get Project X ready to go, Oddone estimates R&D will cost about $50 million through 2010. If the project proceeds, construction could begin in 2011 and operations in 2015. If not, says Oddone, “we would patch up the existing complex to finish the program we have with neutrinos and enhance it somewhat, but not to the extent of Project X.” The next step is for Fermilab to present Project X to P5, the Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel of the High Energy Physics Advisory Panel, which advises the Department of Energy and NSF. If the project finds favor, next spring HEPAP would recommend that R&D be funded.

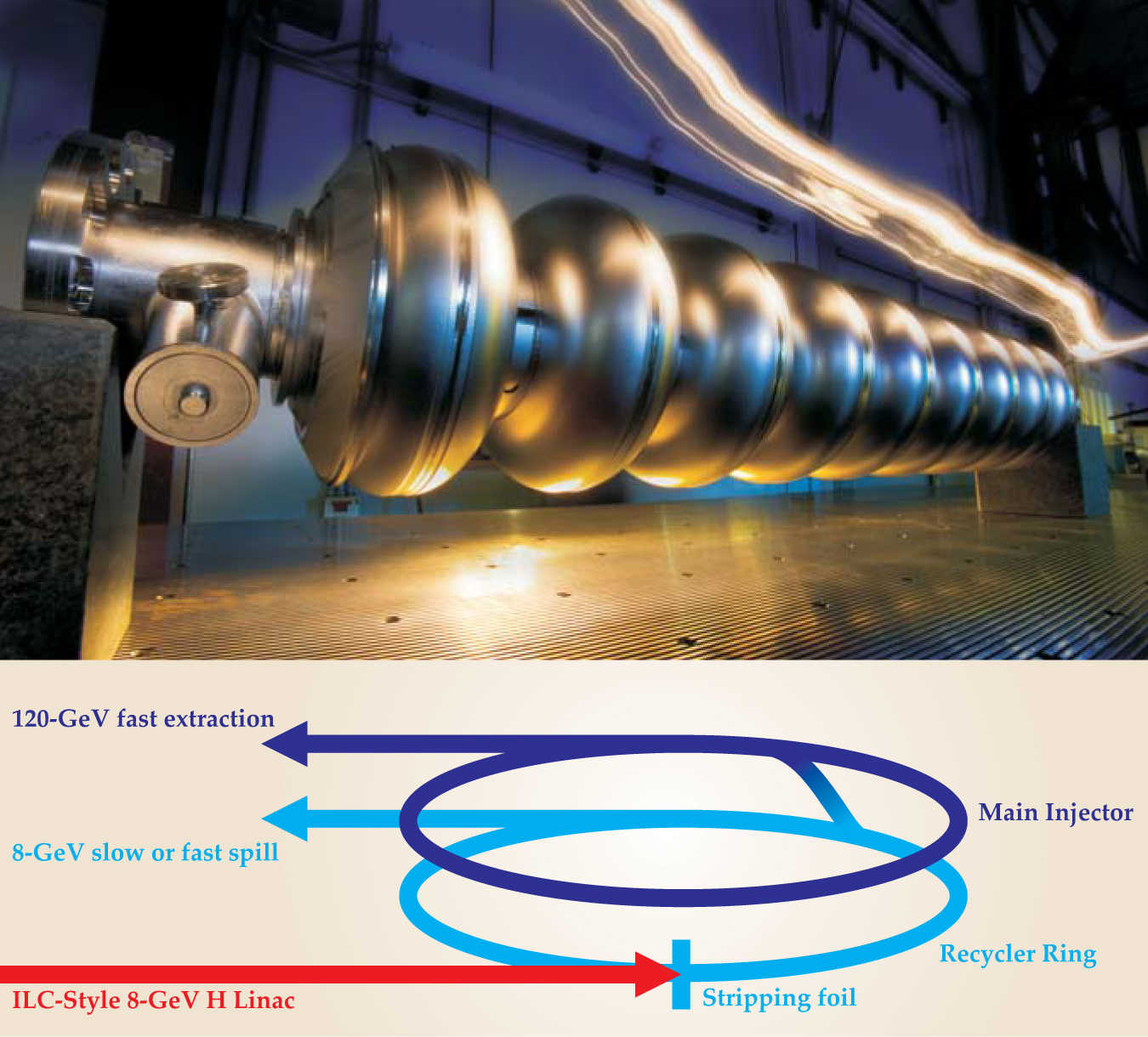

Project X would pump 8-GeV protons into Fermilab’s existing Recycler Ring (light blue in schematic) and Main Injector (dark blue), which would each require some modifications. Project X’s accelrating portion (red) would include around 200 superconducting RF cavities (top) of the sort the International Linear Collider would use. Protons kicked out by the Main Injector would be high energy and high intensity and would be used for neutrino experiments. High-intensity, lower-energy protons could be extracted from the Recycler Ring to create beams of muons and leptons for other experiments.

FERMILAB

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842 US . tfeder@aip.org