Experiments relating to Earth’s inner core raise questions about its age

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3227

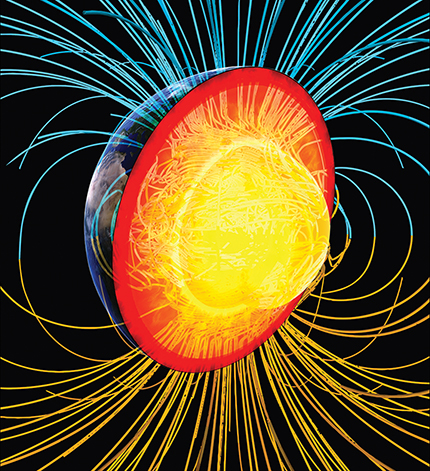

Earth’s magnetic field (illustrated here) is sustained by liquid iron that is continuously churning in the planet’s outer core. Iron that crystallizes onto the solid inner core releases latent heat, which powers convection that drives Earth’s dynamo (see the article by Daniel Lathrop and Cary Forest, Physics Today, July 2011, page 40

DESY

Now two research teams have heated diamond-anvil cells with lasers to determine iron’s thermal conductivity at core-like temperatures and pressures. Kenji Ohta and his colleagues crushed iron wires and determined their electrical resistance, which is inversely proportional to thermal conductivity. The team estimated a conductivity of 90 W/(m·K), a measurement that is roughly in line with the simulation predictions and sets an upper age limit for the inner core of about 700 million years. Zuzana Konôpková and her colleagues measured the propagation of laser-delivered heat through an iron sample. Her collaboration obtained a value of about 30 W/(m·K), which supports the more traditional view of a gradually cooling core with an early-forming solid center. David Dobson, who was not affiliated with either study, notes that the Konôpková result is more dependent on modeling than Ohta’s, and any unnoticed melting of the iron could have skewed the measurement.

Follow-up experiments, perhaps ones that capture electrical and heat-propagation measurements simultaneously on a single sample, could resolve the discrepancy between the two teams’ results. Even in the absence of a solid core, theorists can devise exotic mechanisms, such as the wobble of Earth’s axis, to explain how the planet could have maintained a magnetic field a few billion years ago. (K. Ohta et al., Nature 534, 95, 2016, doi:10.1038/nature17957

More about the authors

Andrew Grant, agrant@aip.org