European Space Science Stretches Lean Budget

DOI: 10.1063/1.1510273

When David Southwood, the European Space Agency’s director of science, emerged in May from several months of feverish strategizing, he delivered some surprisingly good news: ESA will fly all of its planned space exploration missions despite the recent blow to its science budget.

ESA’s crisis began last November, after ministers representing the agency’s 15 member states put the screws to the science budget. For the years 2002–06, science exploration was allotted ά1869 million (euros and US dollars are roughly equal in value). “I got even less than our most pessimistic assumption,” says Southwood. “If I integrate over 10 years—the time scale for space mission planning—it’s about a ά500 million reduction.”

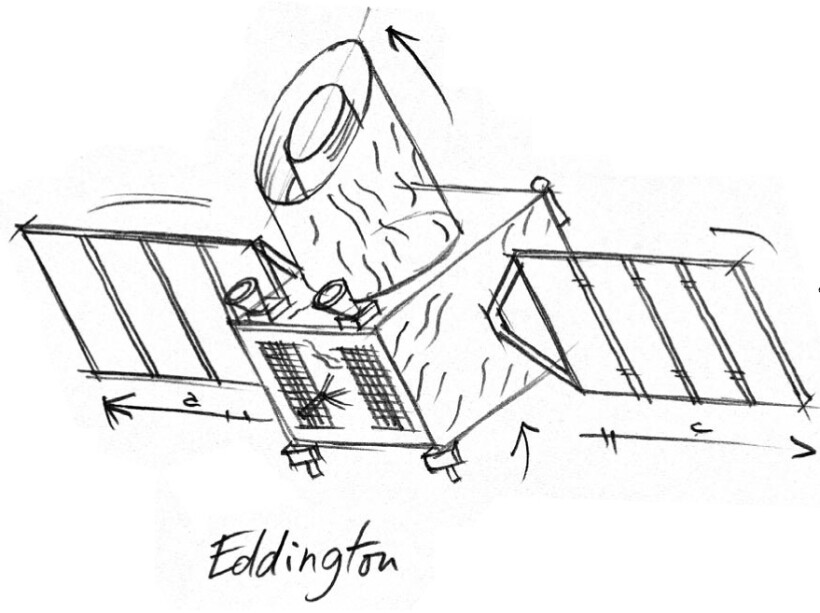

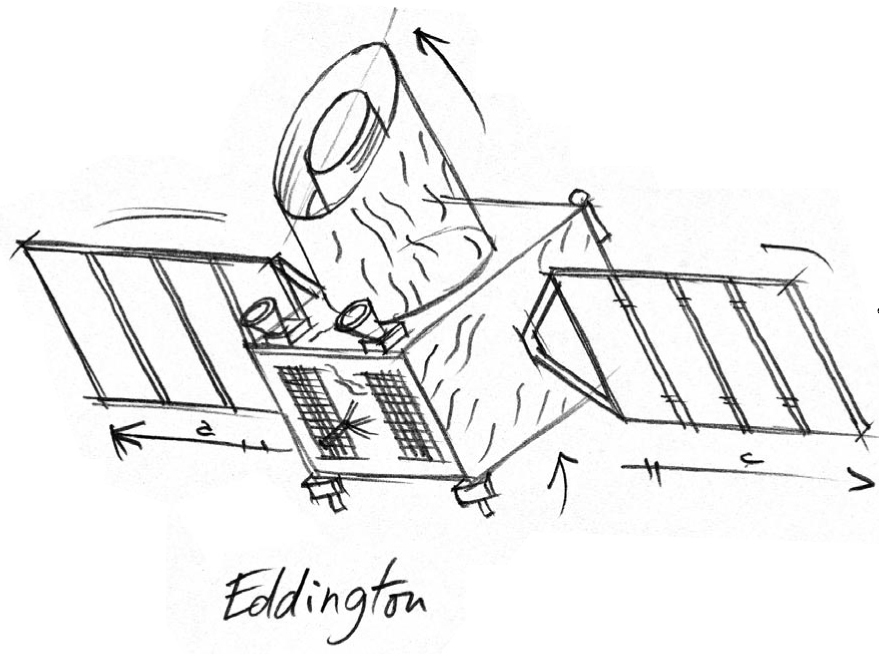

The tightened budget cast a pall over ESA’s space science program. It was widely expected that the galaxy mapper GAIA would be axed. Instead, Southwood and ESA science policy advisers shook up the mission plan, ultimately saving GAIA and even adding Eddington, which will observe variations in light intensity to seismically probe the internal structure of more than 100 000 stars and hunt for planets. Other, smaller missions were also added, such as SMART 2 (Small Missions for Advanced Research in Technology), which will test, among other things, new sensors for precision positioning of spacecraft.

“The ESA executive and scientific working groups have done a tremendous job,” says Bo Andersen of the Norwegian Space Centre in Oslo, who chairs ESA’s scientific program committee (SPC). “We have managed to have no significant loss in science.” Indeed, where the earlier plan included 12 missions in 11 years, the new one, dubbed Cosmic Vision, packs 16 missions into 10 years.

Rabbits and risks

How can more science be squeezed out of less money? ESA’s new plan lumps missions together to exploit technical and scientific similarities. Eddington, for example, is grouped with Herschel and Planck, missions that will explore the infrared and microwave universe and the cosmic microwave background, respectively. The idea is to reduce costs by building the spacecraft and launchers for different missions in parallel. Work and launch schedules within groups are flexible: If, say, Planck faces delays, industry can turn its attention to a partner mission, rather than be paid to wait. Overall, however, ESA’s new plan is less forgiving of delays than before. “I’ll have to make sure that people don’t cut corners just to meet deadlines,” says Southwood.

Industry also came up with a trick to shrink GAIA’s detectors, which will allow the craft to be sent into space with a smaller launcher. “This saves well over ά100 million,” says Southwood. “It’s the biggest savings from a straight technical leap.” The reason GAIA was first in line for the guillotine is because it is a purely European mission, he adds. “If I cancel NGST [Next Generation Space Telescope], I’m betraying America. If I cancel [the Mercury mission] BepiColombo, I’m betraying Japan. GAIA is a European flagship, and I had to think of stopping something big.”

“The new program sounds easy, but it’s tough,” says Southwood. “I am taking a big risk. If you pull rabbits out of hats, people may want you to do it again. I can do this trick only once.” It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, he adds. “You have to put each piece where it matches, so it’s firmly interwoven. We won’t be able to choose individual missions anymore—we’ll have to choose groups that can be done synergistically. This is the opposite of the US approach, but obviously we have the same aims.”

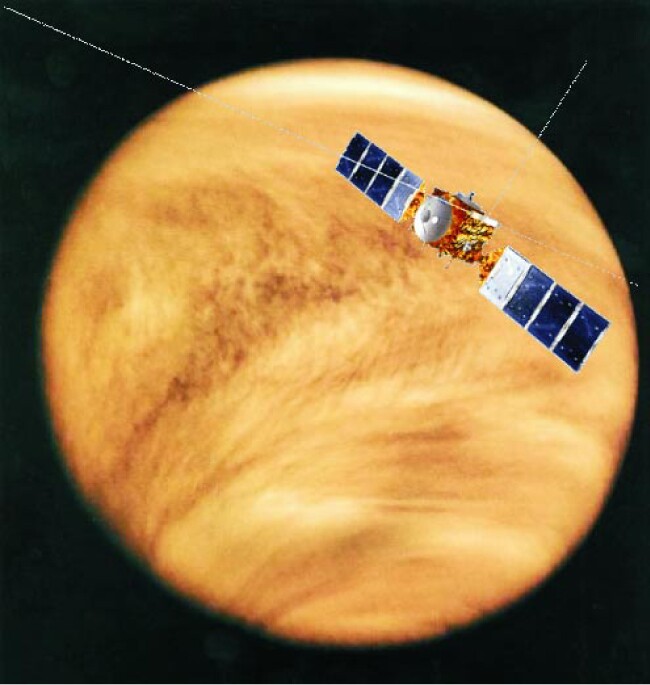

Doubts about on-time instrument delivery nearly caused Venus Express to be withdrawn from ESA’s slate of missions. It would have to fly in 2005, says Southwood, “and I need absolute commitment that I’ll get my payload”—the scientific instruments—“from scientific institutions in the member states. I integrated my doubts, and I felt the risk was too high.” He adds that flying Venus Express later than 2005 would double its cost, “by losing commonality” with Mars Express and Rosetta, a cometary mission.

Planetary scientists argued that ESA’s program would be weak without Venus Express. In mid-June, when it looked certain that the mission would be scrapped, Venus Express coordinator Dmitri Titov, of the Max Planck Institute for Aeronomy in Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany, said, “between Mars Express in 2003 and BepiColombo in 2011 or 2012, there is a big gap in planetary missions. This means not only a lack of data and a lack of new discoveries, it means that the planetary community in Europe will leave their labs. So I think it’s very worrying.”

Venus Express got a reprieve at the 11th hour: On 11 July, barely leaving time to meet the 2005 launch date, ESA decided to start work on Venus Express, and it gave the national agencies involved until mid-October to pay for the payload. Says SPC chair Andersen, “If, by then, the payload situation is not resolved, the mission dies.”

New ways of interacting

Venus Express’s brush with death is a warning that other missions will be canceled if the national agencies don’t commit early to providing payloads. “It’s clear that ESA member states have a money problem,” says Andersen. “But it’s not just that. They’re providing payloads to NASA. It’s their prerogative, but it undermines Europe as a whole.”

Participating in various space programs creates a dilemma, admits David Hall, the British National Space Centre’s director of science. “The problem is that if there are gaps in a particular discipline [at ESA], it’s very attractive to go to other space programs.” The UK, Hall adds, “keeps about 15–20% [of its space science funding] aside for participating in programs of other major agencies. Most countries have that.” In the past, adds Hall’s counterpart in Germany, Gernot Hartmann, “we had more money. Now the priority on supporting ESA missions remains, but the potential for [other] international cooperation has diminished.”

The new ESA strategy will lead to new ways of interacting, says Michael Grewing, director of the Grenoble-based IRAM (Institute for Radio Astronomy at Millimeter Wavelengths) and chair of ESA’s space science advisory committee. “The crucial element—it’s not really a change, but it will have to be more tightly controlled—is the harmonization of time scales. It’s a managerial and financial matter, and it means that national budgets have to be adjusted accordingly.” But, he adds, “the last thing we want is to discourage scientists from taking initiative and looking for opportunities for their science. We should not lose this readiness to show interest, even though it will unavoidably lead to overbooking and frustration from time to time.”

Eddington, a mission to study stars, was added to the European Space Agency’s revised science plan.

ESA/C. VIJOUX

A trip to Venus remains in ESA’s plans—for now. The planet is shown here with an artist’s rendering of Mars Express, which will form the basis for the Venus Express spacecraft.

AGUSTIN CHICARRO/ESA

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org