Duke Beams Hard Gamma Rays, Soft X Rays

DOI: 10.1063/1.1537901

The ultraviolet free electron laser (FEL) at Duke University is being stretched technically in two directions: An upgrade to the laser-based High Intensity Gamma-ray Source (HIγS, pronounced “higgs”) promises to deliver more flux, higher energy, and circular polarization; and, at lower energies, a team of Duke physicists has coaxed the laser to produce soft x rays.

In the HIγS, lased light from one bunch of electrons in the FEL is back-scattered from the next bunch. The facility’s breakthrough “is the use of intracavity power to boost the HIγS intensity by up to three orders of magnitude,” says Vladimir Litvinenko, associate director for light sources at the Duke Free Electron Laser Laboratory (DFELL). Even without the upgrade, adds Norbert Pietralla of the University of Cologne in Germany, the HIγS is unique. “There is no other facility in the world with the intensity, plus the energy tunability and the polarization.”

Due largely to a new booster injector and a radio-frequency accelerating system, the upgrade will extend the gamma energy range to 2–200 MeV—a fourfold increase in the peak energy—and boost the maximum uncollimated flux 100-fold, to 5 × 1010 photons per second. Helical wigglers in a new FEL will provide circularly polarized gamma rays in addition to the already available linearly polarized beams. The upgrade is due to be completed in 2005, with the bulk of the nearly $6 million tab being footed by the Department of Energy.

Pions and helium burning

“The driver for this upgrade is getting to 150 MeV,” says Duke physicist Henry Weller, who has propelled the HIγS into a central role at the Triangle Universities Nuclear Laboratory, a consortium that includes Duke, North Carolina State University, and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “Once we can get to this energy, we will produce pions. We want to measure the π 0 nucleon scattering length. We are trying to establish if isospin symmetry is broken because of quark mass difference and get a measure of that difference.”

Probing pions may be the top priority at the HIγS, but 35 or so users from a half dozen countries have in mind a host of nuclear structure and astrophysics experiments. One new class of experiments stems from the spin crisis’ in the nucleon,” says Weller. “What internal structure carries the spin?” Using gamma rays to split nuclei like those formed in nucleosynthesis in cosmic explosions is another hot area, adds Pietralla. In earlier experiments with the HIγS, he says, “we found that claims about the existence of magnetic dipole strength at the particle separation energy threshold were invalid. It was very exciting to find something that was not expected. That is the fuel of science.” Nuclear astrophysicist Moshe Gai of the University of Connecticut plans to use the HIγS to bombard oxygen in carbon dioxide gas with gamma rays to create helium and carbon. “The fundamental question is, What is the carbon-to-oxygen ratio at the end of helium burning?” says Gai. This ratio will reveal whether Type II supernovas collapse into black holes or neutron stars, he adds. “These measurements will push the HIγS to the limit. We will need everything they can give us.”

Other HIγS applications include calibrating a detector for MEGA, the Medium Energy Gamma-Ray Astronomy space mission spearheaded by Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and, for DOE, developing methods for monitoring the aging of nuclear warheads and for analyzing vats of mixed nuclear waste. “Let’s say you have an inch-thick block of lead,” says Litvinenko. “X rays won’t get to the other side, but 5-MeV gamma rays will be attenuated by only a factor of two, so you can see through big and heavy objects.”

Soft x rays, soft samples

The HI γ S is the brainchild of Litvinenko, and it uses an FEL he brought to Duke from his previous post in Novosibirsk, Russia. (Duke’s other FEL, the infrared Mark III, is the subject of a lawsuit involving property and contractual issues brought by founding DFELL director John Madey.)

In an unrelated development this summer, Litvinenko and his team produced soft x rays. “We are operating the free electron laser in the deep UV—250 nm—and then generating harmonics,” which have higher energies, Litvinenko says. “So far, we have seen the second, third, fourth, and fifth harmonics from a gigawatt pulse.” The harmonics yield coherent radiation, tunable from 50 nm to 130 nm (roughly 10 to 25 eV). “Our only competitor is DESY, in Germany, and we are just a small lab,” he adds.

“My goal is to reach the water window,” says Litvinenko. At around 4 nm, he explains, “water doesn’t interfere with [obtaining] high contrast images of biological material.” What’s more, says Litvinenko, his team has generated 100-femtosecond pulses, “and this is the time scale for chemical changes. You can study real dynamics on a quantum level.” (See Neville Smith, Physics Today, January 2001, page 29

Helical wigglers will add circularly polarized radiation to the repertoire of the High Intensity Gamma-ray Source at Duke University.

VLADIMIR LITVINENKO

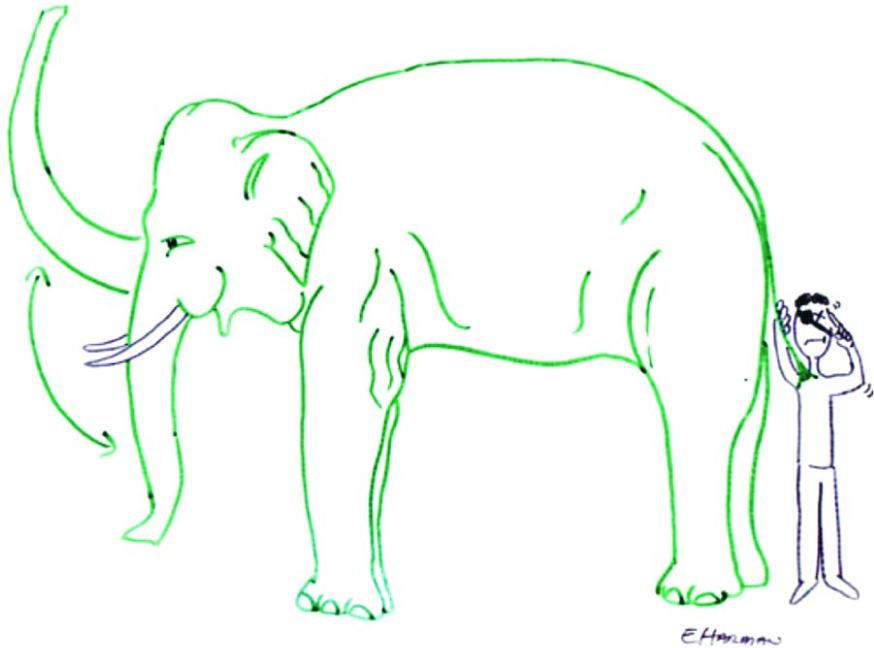

Divining whether an elephant’s trunk points up or down without being able to see is a good analogy for scientists’ long and, so far, futile search for the carbon-to-oxygen ratio in the helium-burning cycle in stellar evolution, says the University of Connecticut’s Moshe Gai, who hopes the High Intensity Gamma-ray Source will remove the blindfold. In this analogy, the curve of the elephant’s trunk represents Coulomb-corrected cross section versus energy at low energies, for which the helium-burning behavior in stars is not known.

ERIC T. HARMAN

More about the authors

Toni Feder, American Center for Physics, One Physics Ellipse, College Park, Maryland 20740-3842, US . tfeder@aip.org