Crevasses may make ice shelves more stable

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.1427

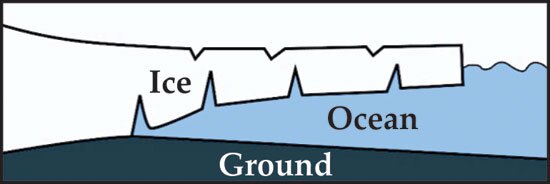

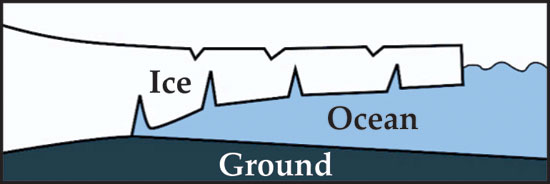

Crevasses may make ice shelves more stable. In Antarctica and elsewhere, ice sheets and glaciers flow down toward the coastlines and continue out into the ocean, where they form thick, floating ice shelves like the one sketched here. Such shelves eventually break, through calving or large-scale collapse. Crevasses on ice shelves are thought to contribute to those processes, but studies of their contributions have mostly focused on the stresses and dynamics near a single crevasse. New theoretical work by Wendy Zhang, Douglas MacAyeal, and colleagues at the University of Chicago considers multiple crevasses and shows that collectively they can add mechanical resilience to ice shelves. In a crevasse-free ice shelf, disturbances from ocean waves, tides, and storms will spread through, and flex, the entire shelf. But as the researchers demonstrate, a periodic arrangement of crevasses forms a bandgap. Like bandgaps in numerous other systems—including photonic crystals, semiconductors, and even underwater sandbars—the crevasse-induced bandgap blocks excitations in a certain range of frequencies from propagating through the ice shelf; instead, the flexing is confined to a small region near the shelf edge. The team finds that the bandgap persists in the presence of some disorder, such as in the crevasse arrangement or the shelf thickness. The ice-shelf responses within and outside the bandgap, suggest the researchers, may play a role in the differing regimes of ice-shelf evolution. (J. Freed-Brown et al., Ann. Glaciol., in press.)

More about the authors

Richard J. Fitzgerald, rfitzger@aip.org