Cosmic experiment is closing another Bell test loophole

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.2051

For decades, physicists have performed versions of John Stewart Bell’s famous test to confirm that quantum mechanics is indeed as strange as it appears to be. None of those Bell tests

By using light from stars in the galaxy to determine the measurements performed on pairs of entangled photons, researchers have demonstrated a violation of Bell’s inequality. The results appear in a study

The clever experiment builds on the already overwhelming evidence that quantum mechanics is not secretly rooted in the classical concept of local realism. It also adds an important safeguard: Unlike previous experiments, the cosmic Bell test ensures that the choices of measurement settings are free of influence from causally connected events that occurred just before the test.

Last year, separate teams at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, NIST, and the University of Vienna performed loophole-free Bell tests

Yet as Jason Gallicchio

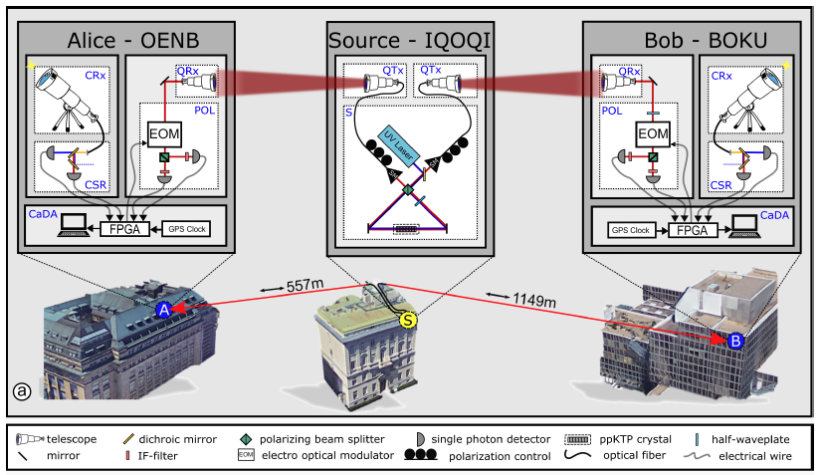

The cosmic Bell test required two stations (A and B) equipped with telescopes to observe starlight and instruments to capture and measure entangled photons from the source station (S).

J. Handsteiner et al./arXiv 2016

Ruling out that unlikely yet plausible prospect requires setting the detectors via causally disconnected sources, wrote Gallicchio, Friedman, and Kaiser. Their solution: Use the light from quasars located on opposite sides of the visible universe to determine the detector settings. If such a cosmic test revealed a violation of Bell’s inequality, then the only way hidden variables could be involved is if they conspired to rig the detector settings billions of years ago—long before the formation of the planet on which the detectors reside.

The scientists haven’t yet used quasars in a Bell test, but they have used Milky Way stars. Working with Anton Zeilinger’s quantum optics group

Like the results of every other published Bell test, the cosmic version revealed a violation of Bell’s inequality. But this new finding demonstrates that if hidden variables intervened in the measurements, they did so at least 575 years ago because the closest star observed in the experiment is roughly 575 light-years away. As the researchers write in the arXiv paper, their work “represents the first experiment to dramatically limit the space-time region in which hidden variables could be relevant.”

The researchers say that in addition to tracking quasars, future experimenters could rely on patches of the cosmic microwave background or primordial gravitational waves to set their detectors. The farther those intrepid scientists push back, the more we can be confident that the universe follows the probabilistic set of rules that have left physicists scratching their heads since the development of quantum theory a century ago.

More about the authors

Andrew Grant, agrant@aip.org