China raises stakes on space arms race

DOI: 10.1063/1.2718749

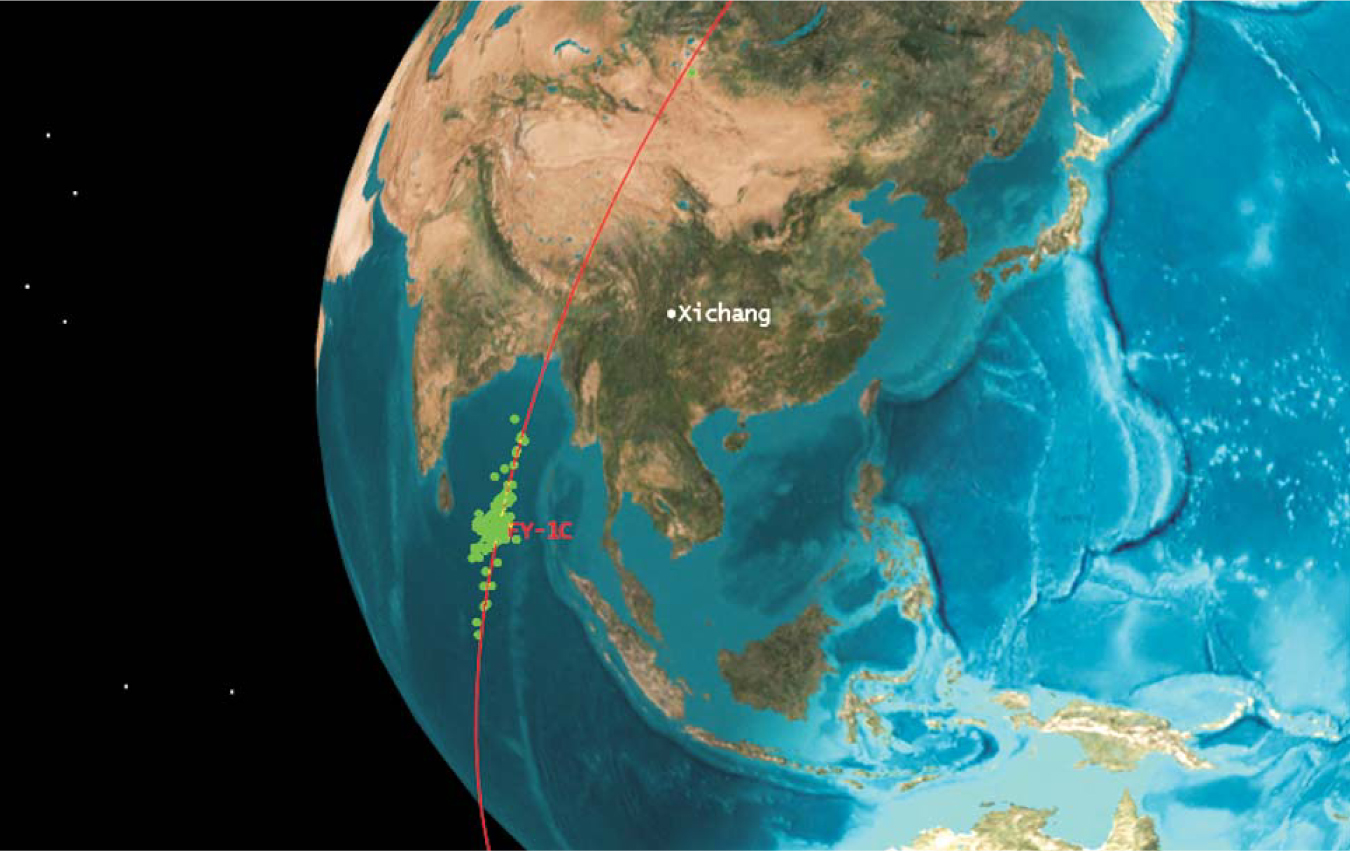

China’s 11 January shooting of a satellite with a ground-to-space medium-range ballistic missile sparked concern worldwide about space debris and about the threat of a reinvigorated space arms race. The destruction of the Feng Yun-1C, an 850-kg retired weather satellite, marked China’s first successful test of an anti-satellite weapon. Ironically, the test came just weeks before China was to host the 25th meeting of the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee.

According to NASA’s orbital debris program estimates, the collision scattered more than 35 000 shards larger than 1 cm. The North American Aerospace Defense Command has counted 2500 pieces of debris larger than 5 cm, making the collision the largest space debris event in recorded history (see page 100

“Of the 2782 satellites we have data for, 1860 satellites pass through the region now affected by debris from the Chinese test,” says T. S. Kelso from the Center for Space Standards and Innovation in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He adds that trying to calculate whether a piece of debris will hit an active satellite is like “trying to assess the risk of someone in a group of people you know getting killed over the next 10 years.”

“How long debris stays in orbit depends on the altitude of the breakup,” says David Wright of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Wright and Wang Ting of the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics have calculated that more than half of the debris will stay in orbit for at least 20 years, compared to months for a lower-altitude collision.

The test came as a surprise, even to some parts of the Chinese government. The Second Artillery Corps, which fired the missile from Xichang Space Center, answers only to President Hu Jintao. “No one is exactly sure why or how the decision to test was made,” says Wright. The world waited 10 days for an official response from the Chinese government: On 21 January, foreign ministry spokesperson Liu Jianchao stated that the test should not be considered a hostile act and that China was not participating “in any arms race in outer space.”

Almost immediately the US released its own response. “The US believes China’s development and testing of such weapons is inconsistent with the spirit of cooperation that both countries aspire to in the civil space area,” said National Security Council spokesman Gordon Johndroe. “We and other countries have expressed our concern regarding this action to the Chinese.”

China’s recent test “is comparable to what has been done by the US in the past, but in the context of the current state of space usage it is an escalation,” says Harvard astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell, who tracks rocket launches and activity. “The debris issue is particularly worrying.” The US and Russia abandoned the testing of anti-satellite weapons in 1985 and the early 1990s, respectively, because of the risk that the debris produced would destroy active satellites.

Since 2002, Russia and China have pushed for discussions with the US over the development of a new treaty outlawing a space arms race. However, the US refused to join such talks and the National Space Policy (NSP) released by the White House last October states that the US “will oppose the development of new legal regimes or other restrictions that seek to prohibit or limit US access to or use of space.”

The NSP also states that the US will “seek to minimize the creation of orbital debris” because of NASA’s planned human spaceflight missions, the dependence of the US military on spy satellites, and the significant number of commercial and weather satellites in low-Earth orbit that could be affected by debris. At a meeting last month in Vienna, Austria, the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space discussed draft guidelines on mitigating debris. Alooming concern is that low-Earth orbit might soon suffer from the Kessler syndrome, in which the amount of orbital debris becomes so high that collisions cause a self-generating cascade that could limit satellite and human spaceflight operations for decades.

“If there is any silver lining to the Chinese testing cloud,” says Theresa Hitchens, director of the Center for Defense Information, a Washington, DC, think tank, “it is that the whole world is now extremely aware of the dangers of space debris. It is my hope that this will spur nations not only to take stronger mitigation measures but to push for a binding agreement to bar any future testing or use of debris-creating weapons.”

A threat? Space junk from the weather satellite annihilated by China’s anti-satellite missile test spreads into a polar orbit. This composite image was made two hours after the collision; for an image at a later time, see

STK-GENERATED IMAGE COURTESY OF CSSI

More about the authors

Paul Guinnessy, pguinnes@aip.org